There is a group that has been organizing the Clinical Education Reform, called CIREC. The Clinical Education Reform Implementation Committee (CIREC) brings together professors, students and members of the academic community to put into practice the formal lines of the New Clinical Education Reform.

The first big step involved in designing this syllabus reform was to look at the pedagogical objectives of the various subject areas and cross them as if there were only one.

For those who choose Medicine and reach years 4 and 5, they must be able to do a clinical case, know how to treat symptoms, assess some disease patterns. A doctor, regardless of his specialty, has to deal with this reality, when patients report a mixture of symptoms, but are not sure what they are complaining about. This happened when it became clear that two medical disciplines had such similar educational objectives that it was understood that it was necessary to innovate, adapt teaching to new social dynamics. Compiling disciplinary materials and defining all the objectives, looking at the portfolio that medical students must know how to solve, regardless of the clinical area they choose, required a new integration of disciplines, but with new perspectives of action and time.

Talking about a new Education Reform means talking about interdisciplinarity, assessment, reduction in the student/teacher ratio, integration of new disciplinary contents, or new academic perspectives, as is the case with Surgery.

The end is one, bring together what was dispersed and segmented and turn it into a single common subject.

After talking last month to the CIREC coordinator, Professor José Ferro and the general evaluation of Professor João Eurico da Fonseca, we spoke to the work teams who over these months worked to produce a final document.

We divided what will change according to large areas of action. And we listened to the people who paved the way for a new education that aims to prepare the best doctors of the future.

This was the sequence of interviews that we did over the course of a month.

Interdisciplinarity

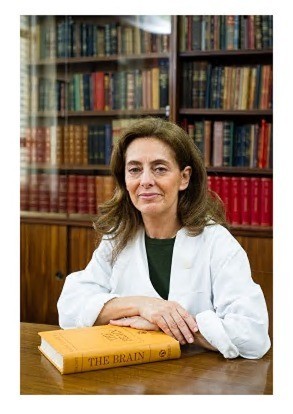

Isabel Pavão Martins is Associate Professor with Aggregation at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon (FMUL), Responsible for the Neurology subject, Director of the Department of Medical Education (DEM) and member of the CAEC and CIREC.

The neurologist plays a fundamental role in coordinating the DEM, which is responsible for various training courses for FMUL Professors. She has an active voice in changing and reformulating assessments, as well as in greater interdisciplinarity between academic areas.

She is aware that this new education reform will pose several challenges for lecturers and that the focus of teaching medicine will no longer be centred on the subjects, but on solving day-to-day clinical cases, which makes it possible for students to have greater contact with different clinical contexts.

You are responsible for various teacher training activities. With this new education reform, are there any aspects that change in the preparation and implementation of these training courses?

Isabel P. Martins: The clinical education reform aims to improve learning in the clinical years through more integrated teaching and better teacher/student ratios, introduce new skills needed for clinical practice at the beginning of this millennium and adapt teaching methods to the new generation of students born in the digital age.

The reform will, therefore, include not only a syllabus reorganisation but also the introduction of new teaching methods, more centred on the students and on active learning techniques in which the students engage and play an active role in their learning, and new assessment methods, such as the semester practical exams in the OSCE format.

The Department of Medical Education has provided training courses aimed at these new aspects, and, together with the Pedagogical Council and the CIREC evaluation unit, we will also provide training regarding the preparation of questions and the more practical and operational aspects of the OSCE. We intend to have at least one person in each subject involved in the training.

What challenges does this new education reform pose for lecturers?

Isabel P. Martins: This reform poses several challenges to lecturers. First, there will be a change in the focus of teaching, which will be more centred on the way patients present themselves and less focused on the subjects. We will have to think about medicine in terms of clinical problems that may involve several subjects and leave aside the presentation of topics according to separate disciplinary areas, which do not correspond to reality. This perspective requires a greater effort to bring together subjects, some of which will be taught in multidisciplinary seminars. This organization of topics is also fundamental for shaping the assessment. A question about loss of consciousness, for example, involves both the Internist and the Cardiologist, the Neurologist or even the Psychiatrist, as it concerns all these subjects and it makes no sense to be addressed by each one independently. This approach encourages differential diagnosis and critical thinking on the part of students.

On the other hand, with regard to practical and theoretical-practical teaching, we will have smaller practical classes with greater teacher-student proximity. There will be increased opportunity for students to contact patients in different clinical contexts and greater involvement of students in their own training. This can be done through case presentation, preparation and discussion of topics, flipped classroom, debates and other techniques that are included in active learning, as opposed to passive learning in large amphitheatres, where students only listen. These are also major challenges for lecturers with regard to the pedagogical methods that they will have to use and adapt to the characteristics of their respective subjects.

We're going to have a big change in student assessments. How do you see it?

Isabel P. Martins: Until now, our system was characterized by a fragmentation of contents into small topics that students studied or memorized intensely in the weeks before the exam and then soon forgot in order to study for the next exam.

I often asked my students, in practical classes, when they had started studying and they said that they only started preparing at the end of December, that is, for the exams they would have at the end of January. This has always struck me as absurd and a total waste of opportunities. To think that students had spent 3.5 or 4 months seeing patients without reading anything about what the patients had was ridiculous. They watched the neurological exam passively, but only really studied it after the classes ended, that is, before the practical exam, when they could no longer ask the lecturer questions. None of this made sense.

It is necessary to learn to allow the learning to be consolidated, and to review and reflect on it through the cases that are observed, already with some knowledge. This is for me the biggest advantage of having a real continuous assessment, which will differentiate students according to grade, and only a single exam at the end of each semester with all the contents.

We want to train doctors who are able to integrate what they observe in the various subjects and make the most of the topics and cases they are exposed to. This learning process is a slow and progressive process that cannot be achieved 15 days before the exam.

In this sense, I would like to draw the students’ attention to the following. Next year it will not be possible to study just before the exam. Students will have to study throughout the semester and ideally they should even read/view some pre-recorded classes before the semester starts, as they will have two very intensive initial weeks. There are no small topics that can be learned in 10 or 15 days and then hope to have good grades. Students will be faced with a single multiple-choice test and a single practical exam, where everything they were exposed to can be asked. This exam is more like the PNA (National Access Exam), which will be fundamental in their future lives.

What improvements would you highlight in this medical education reform?

Isabel P. Martins: I think the main improvements are:

- The approach by objectives and competences that can make teaching and assessment clearer;

- The organization of contents in an integrated manner and directed to the way patients present themselves;

- Improved ratios;

- Theoretical preparation focused on the first weeks of the semester, in order to prepare students for practical education and to have time for autonomous study alongside clinical experience in the following 12 weeks;

- Integrated assessment;

- Introduction of emerging skills.

What year are you responsible for? And what changes in teaching this year?

Isabel P. Martins: The Course Unit that I coordinate is part of year 4. Changes are identical in all areas. The structure of the semester changes, with the concentration of theoretical teaching at the beginning, the introduction of integrated seminars that involve the entire Course Unit, the continuous assessment will have slight differences and naturally our CU will integrate the semester assessment.

Another main player of the new clinical education reform is João Forjaz Lacerda, Full Professor, Director of the FMUL Haematology University Clinic, President of the Ethics Committee of the Lisbon Academic Medical Centre, who, in addition to being the Coordinator of the International Cooperation Centre, is responsible for coordinating the new IMDM Year 4 syllabus.

A truly remarkable year for medical students, when the integration of surgery into medical education will represent “one of the great barometers of change”.

About the new assessment methodology (continuous assessment), “copied” from the British and Dutch education systems, João Forjaz Lacerda believes that everything will depend on the level of the students’ commitment throughout the journey.

In your opinion, why is the new reform so important?

João Forjaz Lacerda: It has been necessary for many years. The degree structure was not aligned with the pedagogical needs of the students, it had several redundancies and very little integration of knowledge.

As coordinator of the new Year 4 syllabus, what will be your role in this change?

João Forjaz Lacerda: Medicine/Surgery represent about 60% of the entire year 4, so this unit will be an essential element and one of the great barometers of change. It's up to me and to Professors Fausto Pinto and Paulo Costa to coordinate it. Fortunately, there are professors with PH.Ds in all disciplinary areas who have great dedication and a sense of mission, and who are doing remarkable work in terms of organization and integration in their respective areas.

One of the most striking changes in the new reform is precisely the assessment system. Do you think students will be better prepared in light of the new assessment model?

João Forjaz Lacerda: The students’ level of preparation will depend a lot on their commitment, whether or not they study continuously and take advantage of the opportunities offered to them. The introduction of the OSCE will have the purpose of evaluating knowledge and attitudes in an objective and more easily comparable way. In our opinion, continuous assessment only makes sense if it is based on objective data. If this is not possible, the assessment should predominantly focus on the multiple choice test and the OSCE.

As one of those responsible for establishing international protocols in our Medical School, I would like to ask you if this educational proposal will open doors for the creation of new synergies with more international entities? Which? And in what way?

João Forjaz Lacerda: It's a major need for the Faculty. In order to facilitate mobility, it will be essential that year 5 Medicine/Surgery adopt the same model that we are developing. The existence of rotating classes with the same duration of practical classes will allow to see years 4 and 5 as a continuum, making it possible for international students to join disciplinary areas of years 4 and 5 according to their needs. This is a complex topic that I cannot explain in a few words, but these are some of the general principles.

In your opinion, should we open places for international students?

João Forjaz Lacerda: I believe your question concerns admissions for international students from year one. Entry into the Medical Degree at European universities is very competitive, and Portugal is no exception. What seems essential to me is that the admission criteria is identical for everyone. There would certainly be a lot to say about the topic, desirable entry methodologies, existence or not of structured interviews, etc.

Even with this restructuring of the clinical education model, when we look at the offer of the Medical degree by private institutions, how does our Faculty stand in terms of competition, when it comes to teaching?

João Forjaz Lacerda: I believe that our Faculty only has to worry about itself. We have some characteristics that are very difficult to reproduce, even internationally. We are the largest Faculty of Medicine in the country, affiliated with the largest general hospital in Portugal, where all medical and surgical specialties are available 24/7. We share the campus with one of the most prestigious research institutes in Europe, which is the Institute of Molecular Medicine, an integral part of the Faculty of Medicine. We must increasingly capitalize on this unique setting.

Assessment

Joaquim Ferreira, Interim President of the Pedagogical Council, Neurologist and Director of the Pharmacology University Clinic, is responsible for the entire assessment area. The assessment must be, in the end, the confirmation of whether the students have achieved the objectives relating to clinical knowledge, outlined from the beginning of the process.

As the Professor explains, the great challenge, even for the lecturers, is to "get rid" of the traditional concept of the various disciplinary areas and look at the major areas in a more interdisciplinary way.

“In the end, what we want is that students know how to conclude that a headache may be a serious illness and that they should request a CT scan and not classify this same headache in detail, even if this classification is absolutely correct. But if later they do not know what to do with that headache complaint, it means they do not know what the next step after the CT scan is, which would be the discovery of something relevant from the patient's treatment point of view.”

But how is this assessment done? Through two forms: the OSCE, which assesses students’ skills and clinical reasoning, and multiple choice.

The implementation and testing of all assessment dynamics belong to the two Professors who supervise everything, Diogo Ayres de Campos, who is responsible for the OSCE, and Ricardo Fernandes, who coordinates the multiple choice questions.

In practice, students will only have two mandatory exams, or four if they want to have a second sitting. The first exams will take place in February 2022, when the first semester ends. That's when a multiple choice test and an OSCE exam will be held, with 10 different stations. At each of these stations, a challenge will be posed, collecting data from clinical history, or a semiological manoeuvre, are just two of the examples to consider. From the result of the performance at the 10 stations, the final grade will be reached.

Both exams will include all the subjects learned throughout the semester. There is also continuous assessment, which will have a more formative component and will allow us to understand the evolution of each student. “This way, the students themselves can learn if what is expected of them is being attained. The idea is to homogenize assessments, based on documents and standard grids”, explains Joaquim Ferreira.

The exam period is also shortened, from 5 weeks of exams in year 4, there will be four.

The reason for the changes always has an explanation.

“One of the major criticisms of the commission that evaluated the education system was the excessive number of assessments. They were quite long, there were too many exams, and too much time was spent on assessment”, the Professor explained. If, in the past, each syllabus component had different assessments, even if they were all done at the same time, the best response to this criticism would be to reduce the number of exams, shorten the period allocated to them, freeing up more teaching period, namely for practical in-person classes with students and doing fewer exams.

Reducing the number of exams and shortening the time allocated to the exam period was thus the conscious decision to gain more time for the practice of clinical exercises.

“There is always a component of uncertainty for those who have never tried this new formula. This applies to both students and lecturers, but the grids try to follow the guidelines with the common rules. We had multiple meetings with the course directors and lecturers and this will be a new step for them too. The main question we are asked is what will be the proper way to ask assessment questions in their area. Some mind-sets will have to be changed and this is important to everyone”.

Change must be achieved, but not in a disruptive way, the Professor explains.

How is this new assessment mechanism practiced with the lecturers?

Joaquim Ferreira: Only with practice and frequent meetings, planning together. Each subject area will nominate its representative, who will be responsible for the multiple-choice test and the OSCE. The work will resume in the 3rd week of September, so that by the end of the year everything is ready to be used. In December, there will be a pilot OSCE and a simulation to check if everything is going well regarding logistics, teacher training and student dynamics. In these simulations and final tests, we may use actors to check everything that can happen in the most realistic way possible. The passage of students from classroom to classroom must be very well tested. It cannot have flaws. This is because they move between physical spaces after everyone has done the same station so that information is not exchanged between those who have already completed it and those who will still do it. Each station has a duration of 6 minutes.

It's up to us to train the lecturers as much as possible, inform the students and carry out all the planned rehearsals so that everything runs smoothly. But we are certain that the novelty factor will weigh on everyone. And even from the point of view of the various bodies of the Faculty, if there is something that is unexpected or unforeseen, we are all ready to change and correct it, not wanting to harm anyone's balance.

This breakthrough is what must be achieved, whether from the point of view of lecturers, who have been doing exams in the same way for decades, or from the point of view of students, who of course deal badly with the uncertainty factor.

By condensing the topics and with shorter exam periods, will subjects be lost, or will students be less prepared in terms of general knowledge?

Joaquim Ferreira: The expectation is that everything goes well, but there will always be doubts and that's why we'll set parameters. And if there are warning signs, we will have to change our actions. Both OSCE and multiple choice are no longer new to some subjects, so now let's apply them to all. It is important to mention that these exams mimic real practice. There is no doctor who receives the patient and sees only a clinical part isolated from everything else. The patient is the whole and complains of various symptoms, which are subjective and force us to be integrators.

A student who has 50% on a final exam passes. But the question that arises is whether he has enough knowledge to know how to treat a patient. Why was there another 50% of knowledge that failed? Which school tells us who is a good doctor?

Joaquim Ferreira: We hold on to a set of methodologies that, at least as physicians, we must question. Data in Medical Education question whether this percentage makes sense, choosing 50% of the questions as a crossing point. This methodology is uncomfortable, but we cannot change everything too abruptly. It must be done progressively.

The OSCE is no longer the 50%, the evaluators make this qualitative leap and see if the person is fit.

But we should not take a set of changes to an extreme that may be uneasy. We want a tranquil change rather than deep disruption.

Lower Teacher/Student ratio

Carlos Calhaz Jorge is Full Professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon and Director of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. He also directs the Centre for Medically Assisted Procreation at the Northern Lisbon University Hospital Centre (CHULN) and was recently elected chairman of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE).

For Professor Calhaz Jorge, this “is a fundamental reform that will impose behavioural and conceptual changes in many areas of education, implying the need for lecturers to adapt to new methodologies, which in some cases will be less complex than in others. But I am convinced that everyone will end up recognizing the progress that the reform constitutes and contribute to its success”.

How do you see the modernization of medical education with this new reform of clinical education?

Carlos Calhaz Jorge: I see it as an absolute necessity. Since the last syllabus change, Medicine has undergone huge technical advances. The changes in the means available for teaching and the interaction between professors and students are very profound. On the other hand, the expectations of everyone involved, and in particular the patients, are completely different from about 15 years ago, the date of the last educational reform.

Clinical education, with the obligation to provide technical training that is more integrated and in line with the current reality, has to consider in practice a concept that is often enunciated and, unfortunately, not always implemented – patient-centred medicine. And, besides the classic clinical topics, it has to include other dimensions such as medical literacy, the management of clinical situations and health care, with an emphasis on valuing shared decisions, and teamwork, to name just a few.

In your opinion, what are the cornerstones for the new clinical education reform?

Carlos Calhaz Jorge: Integration and inclusion of new areas of transversal skills. Although it is done in other areas as well, the need for integration was more obvious in relation to the great areas of medicine and surgery. And this integration constitutes the great mark of the reform to be implemented, significantly reducing the tightness of the various specialties and favouring integrated teaching activities, namely, through theoretical-practical classes and joint seminars.

The planned reduction in the number of students in the practical classes will be essential to foster closer and more adequate contact between students and patients participating in these classes. And it will enable students to have a training closer to the reality of the profession in which interaction with people, in their complexity as unique individuals, must be valued at a time when emphasis is placed on algorithms.

Another relevant integration factor is the model for the end of semester assessment, which will include only a written exam and an OSCE covering all the semester's topics. This will end the succession of several partial exams that promote segmented study.

The new transversal skills proposed are part of the objective to broaden horizons for non-classic components, but which are indispensable to modern clinical practice.

Will the 2021/2022 academic year be a learning year, not only for students, but also for lecturers?

Carlos Calhaz Jorge: Absolutely. This is a fundamental reform that will impose behavioural and conceptual changes in many areas of education, implying the need for lecturers to adapt to new methodologies, which in some cases will be less complex than in others. However, I am convinced that all will end up recognizing the progress that reform constitutes and will contribute to its success.

Are there significant changes in the field of Gynaecology and Obstetrics with the New Reform? By assuming that medicine should “look at the whole and not divide the disease and patients into parts”, what are the major changes in the teaching of Gynaecology/Obstetrics?

Carlos Calhaz Jorge: Like, for example, Paediatrics, Gynaecology and Obstetrics have peculiarities that make them very independent from other areas. Therefore, there will not be any spectacular changes in their clinical teaching. However, the use of models/simulators that enable the training of acts whose practice involves a degree of intrusion and privacy that prevent their initial implementation in patients will be increased. And the theoretical-practical classes will also be more about solving specific clinical situations.

For you, what qualities should a doctor have?

Carlos Calhaz Jorge: This is a very difficult answer, especially since doctors are (or should be) constantly developing throughout their clinical life. We cannot expect a young doctor, just graduated, to have the same qualities as an experienced doctor. Neither in his knowledge nor in his degree of maturity.

That said, there are basic personality characteristics (ability to empathize, commitment, moral and ethical values, sensitivity to the suffering of others, clarity in considering situations) on which solid technical knowledge must be based in constant intellectual and, above all, reflective development.

Surgery

Paulo Costa, Full Professor of Surgery at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon (FMUL), Director of the Surgery University Clinic and Coordinator of year 4, talks about one of the central topics of this new educational reform, Surgery.

The syllabus structure for years 4 and 5 will have a reformulation that is not just cosmetic. The time, agreeing or not with the new proposal for the articulation of the subjects to be taught and with the logistics inherent to the accepted format has gone. Now is the time to bring together the actors to make it happen. It is up to us to bring to reality this different architecture that has been proposed to us.

The Faculty will have to adapt to this reality from next September. It will have to believe that this path will be effective for the training of physicians, who will find a time full of changes and even more full of means to gain knowledge in progress. The Faculty will have to monitor in detail, and in real time, each action proposal and the effects resulting from that same intervention – I believe that it will be a time of multidirectional feedback.

The major test to the effectiveness of the change will probably be the ranking of our students in the National Access Exam. This result depends as much on the teaching format as on the pleasure of learning and of teaching how to learn. It's not the syllabus sheets that will drive success.

But the question that was put to me focuses on the new “surgery house”. Surgery is not just medicine with scalpels and a sophisticated range of operative instruments. Surgery is a "mental thing" and "an art of interpreting-performing" - that's how I graduated as a surgeon and that's how I've tried to transmit it to those who are with me in surgery. One does not get a taste, or learn surgery, by reading books or watching videos. Medical students must be exposed to the surgical environment as early and intensely as possible, otherwise surgical vocations will not be awakened (all educational literature reinforces this assertion).

General surgery, when I entered this Faculty, was taught in four “courses” per year. Surgery lost a variety of pathologies, which disappeared or started to have a non-surgical treatment, but gained in sophistication and complexity of diagnosis and intervention. The integration of surgeons in different multidisciplinary decision environments has not made us less surgeons, so we have to continue teaching surgery at different stages of the students' evolution, from knowledge to proficiency.

What was behind some presuppositions of the syllabus reorganisation was precisely the quest for greater integration of knowledge, among the “specialties”. The surgery lecturers have always shared integrated teaching with pleasure and determination. Just as an example, in Surgery I, we always had theoretical classes in oncology, nutrition, intensive care and pathology, among others. This idea has always been present in our planning. This will continue to happen in this new model and its planning is practically complete. More than a reorganisation of contents, we can talk about a different geometry to present them, bringing together areas of activity that are close.

The transition from practical learning to small group teaching (4 students) brought about an atomization of the system, which led to a significant reduction in contact with surgery (8 mornings from Monday to Friday). This is the lecturers’ main concern. Time optimization is not easy to reconcile with the reality of care life. The functions of surgery professors will have to be reviewed and trained, so that teaching at the patient's bedside, in external consultations, in multidisciplinary meetings, in the emergency room and in the operating room, can take place. Students and assistants will have to adapt to a necessary rotation, the class assistant being replaced by several assistants throughout the week, with the emergence of the “role” of the tutor, who will accompany each class on their journey.

It will require from students and lecturers willingness and effort to adapt.

You ask me if I can draw the “right profile for a future great Surgeon”.

The answer is: this profile cannot be drawn. The paths to become a Surgeon, and the required skills are so many that there is no risk of falling into monotony of paths or professional ambitions. The great Surgeon is the one who knows how to efficiently and humanely treat “his” patient, whatever the circumstances.

Asking the “dean” of academic surgeons if it is possible to be an academic surgeon is interesting. Everything is connected, and if it isn't, we have to strive to bring together what is dispersed. Teaching, researching and operating are so integrated into the life of academic surgery that its execution is natural. The intensity and time that, at each moment, we dedicate to each of these aspects, will naturally harmonize throughout life. Sometimes we operate more, sometimes we research more, but the baseline is naturally teaching, in the various stages of improvement that those who come to us to learn are experiencing.

And the administrative activity? It's a price to pay.

I end as I started. This is the time to launch the new syllabus for the benefit of the students of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon.

Cristina Bastos | Isabel Varela | Joana Sousa | Leonel Gomes

Editorial Team