I wait for him to end a phone call and sit down in the corridor, on a sofa whose weather-worn leather appears to tear at any moment. I feel self-conscious of my weight. Yes, I am in a corridor that is much looked-for by all those curious about it, who are mainly from outside this Faculty. Models of brains, posters, rooms where 3D prints are made to simulate brain surgery. At the back door, right next to me, is where Pedro Henriques works and dissects corpses. “Pedro, One day I'll interview you”, I tell him whenever I see him, but I'm afraid of being forgotten there and I always postpone the conversation.

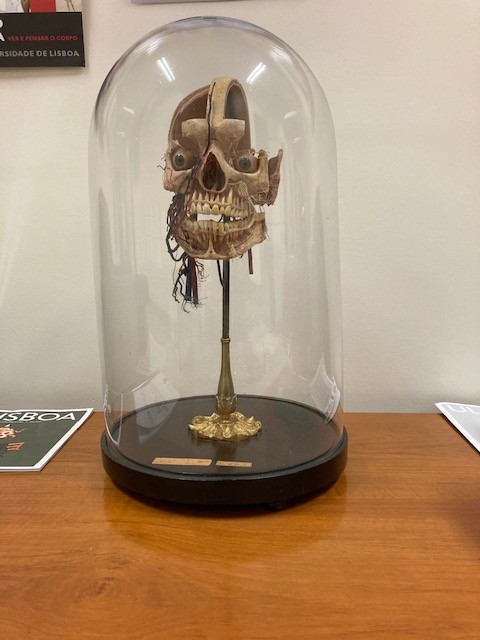

In that cold room that fortunately always has the door closed, there are human bodies, or just parts, diseased organs, pieces of skin with tattoos, foetuses, and a head. It is the head of Diogo Alves, the killer in the Águas Livres Aqueduct, the last man to be hanged in Portugal, in 1841.

He is always cheerful and outgoing in the way he talks to others. He is informal. “Wasn’t our meeting tomorrow? But come in, it's all right, we'll talk today!”, he says in a good mood. With a complete lack of awareness of my ridiculousness, I insist that I was right about the day and time. Still, I realized that I changed everything and changed his plans, but he was no less expansive and receptive.

The office full of books and papers on top of the wooden desk makes it a bit gloomy, and one never knows if is very hot outside, or if it's raining cats and dogs. There is no free space. On the wall, against which there are two large armchairs and a lit floor lamp, there is a cork board covered in photographs that tell a thousand stories and memories, people and ties. Not all are real moments. I'll explain why later.

António Gonçalves Ferreira is Full Professor of Anatomy, Head of the Neurosurgery Service, Director of the Institute of Anatomy and of the University Neurosurgery Clinic, as well as the current President of the Alumni Association of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon. It's the second time I've visited him here in this room. The first time was to talk about the launch of the Manual de Anatomia (Anatomy Manual), which became the learning guide for almost all medical students in the country.

Celebrating his 70th birthday on 23 December, Gonçalves Ferreira knows that that number is with conclusion. Number 70, for the academic and institutional milieu, means retirement. For him, it also means the abrupt end in the labour market and society, which prematurely ages people and takes away their usefulness, even if they still want to have it.

He doesn't mince words, he's quite direct. In fact, he acts with the confidence of the place he occupies, of his age, at work. There are precisely several faces connected to the work that I suddenly identify on that billboard. “How funny Professor, look at Professor Lia Neto, Professor Ivo Furtado… so do you also know Diogo?” I keep going on, without fully realising the intricacies that belong to Gonçalves Ferreira, not me. “Of course I know him, Simão is our doctor, he was my intern, so how could I not know him?”, he answered laughing.

In fact, the few times we met at Faculty events, I always thought of him as an assertive, upfront, direct and good-humoured person.

“Professor, you have met Gwyneth Paltrow? Wow, I always thought she was so beautiful!”. My eyes kept travelling through the photos, trying to absorb all the details. Before introducing me to his children and wife, as well as to some friends, all of them mirrored through the photographs, he explained the reason for such an international presence. “I don't know her, but I'm sorry I don’t!”. He laughs and I do too.

Influenced by the geographical environment where he grew up until he was 17 years old, on the Alentejo coast of Santiago do Cacém, António Gonçalves Ferreira is aware that the fact of being the son of a traditional general practitioner may have affected his personality and some of his career choices. If geography gave him this more expansive and communicative nature, family origins imposed a method and focus on him that would stay with him for life.

Even today, he gives consultations at the practice set up by his father. From those times, little is left. His father died young, when António was only 9 years old. With a strict Catholic education, it was the mother who took care of the two boys in the family. She was a maths teacher who did not for a moment lower the requirement levels. Perhaps due to the natural defence of a single mother who raises her offspring to succeed in life, the children always had to be top students. The place where they lived was part of the diocese of Beja, in the Catholic mapping. The Bishop of Beja visited the family whenever he travelled to Santiago, inherently instilling his moral character as a bishop to the matriarch, the widow.

At the age of 17, he came to FMUL and left his mother's house. He needed to free himself as an almost adult, and essentially from his mother and from one side of religion. Still, at the age of 18, he was President of the Christian School Youth, which he still finds a great school of general organization. In year 3 of the Degree, he abandoned Catholic practices and says that, "if I wasn't almost a non-atheist, at least I was a non-practitioner".

Armando Ferreira, his Anatomy Professor, was his first big academic inspiration. He remembers him in the first class, when the Professor said, in the old wooden amphitheatre, "maybe some of you will become one of the my Anatomy assistants".

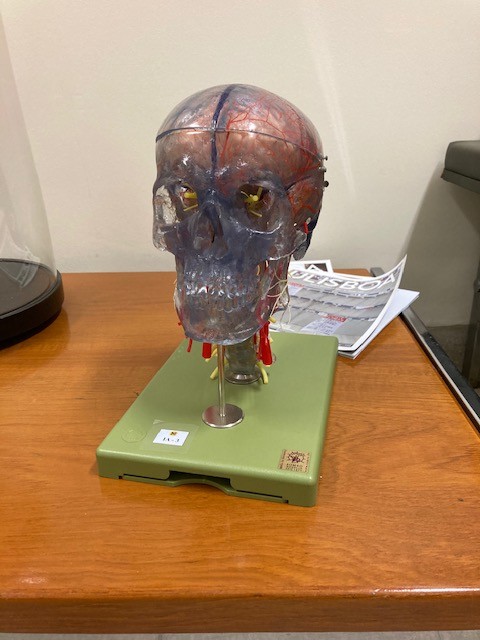

After his first major interest in Anatomy, the Nervous System was the next to pose him new challenges.

Its natural environment thus became dealing with the brain, with Anatomy as an advisor to know how to use the best techniques in surgery.

The particularities of his knowledge, the agile way in which he responded to organizational needs and the influence of his contacts, made him take on roles of great international prominence.

One of the most significant for specialists in their field is the European Association of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery (ESSFN), which he presided from 2018 to 2023. The International Scientific Society brings together neurosurgeons who are dedicated to this field of neurosurgery. It encompasses different areas, from surgery for movement disorders (Parkinson’s, dystonia, tremor), pain, spasticity, epilepsy, and psychosurgery.

Already previously vice president, in 2014 Gonçalves Ferreira was unanimously approved for his current role as president of the ESSFN.

He was also a member of the European Association of Neurosurgery (EANS), the largest Association that covers all areas in the field of Neurosurgery and where Lobo Antunes was European President. Gonçalves Ferreira was president of one of the specific areas, the Research Committee, for 4 years. At that time, he managed to create something that was only done annually with technical training. He started another path of work, the European research course.

Having played a rich and solid international role, the truth is that faced with the arrival of the age of 70, António Gonçalves Ferreira will cease to have Director functions, in both Neuroanatomy and Neurosurgery. He will also stop his hospital functions. He will continue to coordinate Anatomy and Neurosurgery until the end of the academic year, but then he will leave. He never thought that the abrupt cut was a good reflection of societies that are in a hurry to label stages and give people deadlines. Thus, he considers continuing to attend the Service meetings, even if only once a week.

"If not well accepted, retirement can be very painful. When we have invested most of our lives in activities, knowledge and with time increasingly fine-tuning the experience itself, retirement suddenly interrupts all activity". He reflects. "People must go on preparing their succession and leave everything in order so that the areas can continue, but it is also cruel for people to see themselves interrupted from any and all activities".

Even today, he is responsible for the acquisition of the new Neurosurgery equipment, linked to deep brain stimulation. The experience that is required, both regarding the details and the technological scope, make him comfortable to help to decide.

He speaks with a very spontaneous enthusiasm, as someone who is still very excited about what he does. He is quick in his words and ideas, but there is a detail that I discovered today. He speaks faster when the topic is the end of life.

He clearly doesn't like to talk about death. Let's call things by their right name. One doesn't have to talk about death just because one reaches a certain age, or because someone retires. Absolutely not! It is more interesting to confront the change that maturity brings us. It is the Professor who addresses the topic. The fact is that it is always present when doing an interview in the Anatomy Area.

I carried a thread of questions, but I never struggle to follow them, because I prefer to understand where the interlocutor wants to take me. This “blind” path has led to incredible conversations and discoveries.

Among several topics, he said that he recently lost a great friend, whom he had always followed closely in his last life stage facing a fatal tumour.

We talked a lot about learning throughout life, something he has reflected about profoundly.

Today, he knows from direct experience that the deterioration of the human body makes the elements more fragile and volatile, whether for those who get sick or for those who take care of the sick.

In view of the close observation of a real case of Alzheimer's Disease, he mentioned, perplexed, the abandonment of everything that was once at the height of his abilities. Isn't this loss of capacity also a kind of death, with the body still present? I think as he talks, but I choose not to ask.

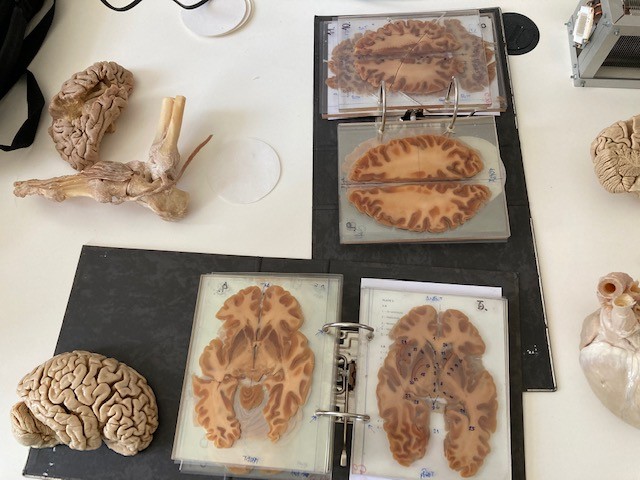

In recent years, Gonçalves Ferreira has been trying to conduct research on deep brain stimulation, in order to alleviate dementias such as Parkinson's, or to treat Epilepsy. Regarding the latter, he was the pioneer Neurosurgeon in Portugal. He explains that by stimulating some areas responsible for memory in the brain, it is possible to bring that lost memory back to life, or even never remembered. The initial study was based on an accidental discovery by a neurosurgeon friend from Toronto. Aiming to reduce appetite and treat the progression of morbid obesity of a patient, it was found that by stimulating a certain part of the brain, it remembered a remote past full of details, as if they were making a live trip to the past. Each time the brain stimulator was turned off, this patient's memory ceased to remember that same past.

Brain stimulation can have beneficial results, such as the end of addiction, or excess pleasure for food or drugs. That's precisely what he did when he operated on the first case of cocaine-refractory drug addiction resorting to Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS), with good results.

As a result of this manipulation, the brain sometimes surprises those who treat it and reveals new functions that were not yet established in textbooks and in clinical experience.

Will we then be able to decode the entire brain knowing how far its range extends? Will we know about the density of memory and distinguish how many layers a person has on his own subconscious, or unconscious, as Freud would defend?

Age is a burden and not an asset. Not so for Asian people, for example...

In several places I know, people who retire continue to conduct their activities quite actively, even having consultancy positions. But in Latin countries there is no such tradition.

Let me give you an example to see the applicability of this. Worldwide, there are few people who can do the most complex epilepsy surgeries. Not long ago a fellow assistant did one, but it was impossible for me to be present. The surgery went well, but he regretted that I couldn't be there, because eventually I could have helped him to respond more quickly to the difficulties he faced. Being six months away from completely leaving the activity, it is more than normal that they no longer need to rely on me, even for the most complicated surgeries. However, it is also true that we can play a very useful role in terms of the qualitative sharing of the surgical experience, especially in the most difficult cases.

I remember when I did a clinical internship in Epilepsy, in Canada, at one of the largest Reference Centres, the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital. Every week they invited Dr Theodore Rasmussen, who was already over 80 years old at the time, but who knew how to read, like no one else, rare electroencephalograms in the face of difficult cases of epilepsy. He continued to be called upon to give his opinion and reflect on the topic.

Often, when taking up leadership positions, this work turns out to be more about managing people and resources than creating, putting hands directly on the actions. This ends up limiting what, perhaps, was the person's main passion. Have you felt this throughout your life?

Maybe I put it in a different way. What I begin to feel, more now, is the collateral role of being a professor. There are very specialized procedures that are not performed every day and which, as time goes by, we let go more and more so that others can grow autonomously. Whoever is in charge of a team ends up not carrying out many actions to make room for those who are still developing their curriculum and need to present work. The fact that we are only present in the most complicated situations and still manage different personalities really interferes with our own task management.

Is managing personalities the biggest challenge for a people’s manager?

It's one of the big challenges, but not the only one. There is the challenge of taking very careful care of the interns (doctors) because they are the real apprentices. A boss needs to have great acumen to understand the potentials and the side that cannot be so valued because they will not be highlighted so much. Another aspect of people management is knowing how to work with everyone on a equal basis, even if we have closer affinities with some persons with whom we identify more.

Can empathy between peers and teams cloud the critical analysis regarding the individual performance of each person?

I don't think so, but the fact is, we have to balance reason and emotions. And the irrational can sometimes threaten this equilibrium.

Please explain this part as someone who has spent his life studying and working with the more cerebral side of human beings and says that there is a strong irrational side.

The irrational is omnipresent, as is the rational. The difference is that the irrational rarely surfaces, but it can be translated into gestures. This shows that the two sides are contaminated, because we don't always know how to make each side watertight. But bearing in mind these notions, it is necessary to know how to manage them.

What made you grow apart from religion at some point in your life?

It was because I felt that traditional Christian practice was very objectionable. It had many rituals, and defends many beliefs and dogmas. But the truth is that afterwards, believers did not practice what Jesus Christ would have preached. Jesus is a historical character that touches and enlightens me especially. Death is the part that I still can't quite accept.

I was going to ask that. But let's talk now.

Immortality, from a molecular point of view, is something we know is happening. There are already the so-called immortal cells. In other words, there is a certain type of cell, tumour or not, that has an infinite capacity to reproduce.

As a clinician, what do you have to say about this immortality?

I regret not living a century later, because there are certain problems that will be resolved in the meantime. In society, we are still conditioned by major diseases that kill, such as Cardiovascular Diseases or Oncologic ones. Well, in large tumours, at least, we will have many solutions in the near future. Other things will be avoided due to vaccines, etc...

Does this power of life give Humanity the divine touch that it never had?

It will! And it is possible that they are realizing this, through technical evolution. On the other hand, I have some reluctance to admit that when a person dies, it's all over! So let's get back to the clinic. Neurologically, I think it really has to be over, dead. The brain has no circulation. It’s over! Every soul we know, in a more organic sense, resides in the brain, and note that I say this as a neuroscientist. So when the brain dies, it's over! Now... (he stops and reflects) irrationally, I have a huge reluctance to accept this. Because the brain, our mental, spiritual life, is something so complex and rich that I have a hard time saying it ends with death.

Do you have difficulty just as a means not to accept death, or because throughout your life and your losses you understood that there was something else that you couldn't explain?

Above all, I think it's a shame that everything disappears. It's a great pity. Of course people will live longer and longer, but you know, I really like science fiction books, they're the ones I read the most. In fact, there are many books that tell us that, sometime in the future, it will be possible to successively replace organs, change our genetic code that says that our cells are going to die at a certain point. And why? Because this code, like all codes, can be changed, it can be reprogrammed.

Is our brain a whole world yet to be discovered?

I think so, but that worries me too. There are many absolutely basic functions for our functioning that can often be regulated in a "sophisticated" way, from a technical point of view as simple as managing a small electrical wire from an electrical current. The possibility and the need to know more really opened a new door to the world of neurosurgery.

What made you connect more to the nervous system?

For many years, I saw Neurology as a very contemplative neuroscience. Excellent diagnoses were made, but the treatment ended up falling short of the evidence of what was diagnosed. There was medication, but the treatment was limited to only there. In Neurosurgery, I felt that, at least, in some points it was possible to do something that interferes more, in a more direct way. And that's what made me dedicate myself to the area. Then I did it, and I was very encouraged by my Professors to achieve this, as was the case with Professor Lobo Antunes. I managed to combine Neuroanatomy and Neurosurgery. And I think that the integration of basic sciences with applied sciences has yet to be further boosted, the education reform would need this greater focus.

In your view, are these two areas still watertight?

These sciences are still very apart. Research nowadays requires large investments and they are made by the agencies that support research in each country. In order to be able to have successive funding to conduct research, they cannot diverge their focus of attention too much, they cannot disperse too much, or try too many areas. In research centres, to ensure credibility, they do not risk much in their research and are always basing it on proven premises, because that is what guarantees them more funding. This means that we are still a long way from a perfect match. Basic science already responds to a lot, but it only responds to the "most urgent" focuses of interest in the clinic area. It cannot be at risk of innovating and dispersing. Probably, the trend will be the for the two areas to become closer, but for now it is very limited.

I was listening to you and thinking how contemplative you've been throughout our conversation. Has it always been like this, or is it maturation and experience that make you like this?

I've always meditated a lot about what I do and especially about what happens around me. But probably the consequences of this in my practice as an institution and people manager have changed. Now...I am still facing a terrible challenge as a Professor of Anatomy, which is my main role at the moment, to stimulate the development of the subject. What happens is that the classic books are still based on the early experiences of anatomists. The advances in microscopic anatomy were always more published in Clinical Anatomy and not so much in Basic Anatomy books. So my reflexion is also around it, it is the path of the razor's edge, between clinical and basic at the same time. But this double path is very difficult to tread and to replicate in the new means.

Where does teaching fit for those who practice Neurosurgery and spend their lives operating and without time for research?

My interns and assistants are nowadays so stimulated to learn and apply the knowledge to practice, to improve surgical techniques and participate as much as possible in the operating room, which is the new dynamic in the market. The development of CVs is like this and the more they exercise and practice, their CVs become stronger. They are faced with so many requests that they lack time and space for research and academia. The real research is above all the basic one and that requires less and less time. In my growing up time there wasn't such fierce competition, nor so many simultaneous activities.

My Assistants work on a part-time basis, precisely because they need the private practice in order to have a more rewarding career. As such, the academy is forgotten, not least because it is not so rewarding. I also think that people are only attracted to knowing more when they already know a lot. But what do I mean by this? As we have this notion that we need to explore some kind of knowledge, we organize hands on courses here at the Anatomy Theatre about using Anatomy in cadavers.

In your opinion, has this integration of Anatomy been successful in terms of teaching? The truth is that if a few years ago the Access Final Exams showed that medical students did not master Anatomy very much. Now in this last exam, it was the Faculty with the highest grades.

Here it must be said that the Faculty, through Professor Joaquim Ferreira, has been concerned with preparing students who are taking preparative tests and thus train their skills. Until recently, only Minho and Porto did it. Harrison's well-known Test, the Specialty Access Test, was just pure study that became absurd, it was about memorising without knowing how to apply the knowledge.

Time is never allied of good conversations that intersect in lines of thought that never objectively reach an end. We ended up in the middle of something that could still have started to be talked about. It is time that often determines the end of something. Once again, time determines the end.

Always with the same level of good spirits, and without ever waning or raising his tone, the Professor made a point of accompanying me to the door and joked, “I'll take you, you will not hide here”.

If there's one thing I'm sure won't happen, it's hiding here, or getting distracted in the corridors of the Anatomy Theatre. There's always this subtle weight that we're all at the end of the cycle, so I'll never want to stay, not for long. But there's always the temptation to come back.

Joana Sousa

Editorial Team