We all know how essential it is to have good mental health in order to enjoy an adequate quality of life.

However, first of all we must specify and understand what is considered to be normal and abnormal. To what extent can an individual be considered as suffering from mental disorders because his way of being and acting is "different" when compared to another way of being that has been established by societies, as said "normal", since there are countless cultural, religious, ethical and cultural differences in the world.

Due to the fact that mental health provides intellectual and emotional fulfilment to all individuals and at the same time supports solidarity and social justice to be a reality in our societies, it has been verified, over the past years, that mental health problems have been the subject of meetings, discussions and the publication of several reports at the highest level from both the WHO, world psychiatric associations and member countries of the European Union.

Although all show prevalence in providing individuals suffering from mental illnesses with effective and high quality treatments, the truth is that they continue to be the target of discrimination and social exclusion, when they are disrespected in their fundamental rights and integrity. In addition, in the economic context, mental health also leads to high expenses, loss of productivity and early disability.

Psychiatry, as a medical specialty, is essential for the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. The training of professionals in this area, whether doctors, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, and social service technicians, is demanding and complex and requires time and experience, vocation and dedication to treat people with mental disorders. Over time, it has been verified that the great technical advances in this area are mainly in terms of human resources.

Also with regard to the tests to be carried out on the mental state of individuals, they differ from country to country in the EU, due to cultural differences, in terms of economic development, health systems and institutional practices.

We have seen throughout human history that there are countless reported cases of mental disorders in the most varied cultural perspectives, both in the area of medicine, history, literature, poetry or even sculpture, while the care dedicated to people with behavioural disorders vary according to religion, beliefs or customs in the societies they were part of.

In prehistoric times, both physical and psychic medicine were based on intuitive and magical aspects, the gods, wizards, demons being held responsible for the diseases people suffered from. Diseases were considered as punishment for sins committed and could only be relieved through the intervention of priests and sorcerers. For people with behavioural disorders, the only way to overcome them was to undergo tribal rituals. However, if they were not successful, they were left to their own devices.

In priestly societies, individuals who showed unequal behaviour were isolated from the others, and considered to be “possessed and demonized people”, being subject to magical rituals and exorcisms.

The ancient societies of Greece and Rome assumed that the crises these patients suffered from came from supernatural forces and demons. The lack of institutions for these patients meant that those who came from wealthy families remained at home, while the poor wandered the streets at the mercy of others' charity or performed very rudimentary services. They were not considered a problem for society, but a family problem.

In ancient Greece, priests and doctors advised that patients should to be treated with compassion, subjecting them to physical exercise, fresh air, pure water, and sunlight. They also provided them with walks and theatrical scenes to improve their “mood”. If patients did not respond to treatment, they were subjected to flagellation.

In ancient Egypt, brain surgeries were already performed and in ancient China there was some knowledge of pharmacology and pharmacotherapy.

As some authors refer, the history of psychiatry began with Hippocrates (460 BC-370 BC), when he developed the humoral theory. In his work Corpus Hippocratuum, he narrated some illnesses such as melancholy, phobias, senile dementia and hysteria. In this publication, he stated that these diseases were the result of an imbalance of moods. Hippocrates considered epilepsy to be a disease that arises from the brain and that most illnesses are the result of mood disorders.

Hippocrates attributed intelligence to the brain and believed that it was the origin of several sensations identified by the human being, such as joys, sadness, laughter, tears, or pain. At the same time, the brain has the ability to see, hear, contemplate and compare beauty from what is ugly, good from what is bad, the faculty to feel fears or the performance of unusual practices. It is through the brain that man expresses himself and speaks, of what his vision and hearing witness.

One of his great merits was to attribute the natural origin of the illnesses and to question the supernatural view of psychic illnesses.

There were several Greek doctors who, influenced by Plato's texts, studied and stood out in the field of mental illnesses, such as:

Asclepiades of Bithynia (124 B.C. or 129 B.C.-40 B.C.) – he believed that mental illnesses were a consequence of changes in passions;

Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC) - considered the father of psychology, made some considerations about intelligence, judgment, imagination and reasoning;

Galen (ca.129-ca.199 or 217) - wrote that both mental functions and psychic disorders originated in the brain. He made several treatises where he described the treatment for diseases considered to be chronic and acute, such as mania and melancholy.

Many of the designations currently used in psychiatry such as paranoia, schizophrenia and many of the concepts of psychoanalysis have their origin in knowledge from Greek culture.

In the Roman Empire, mental patients were not considered accountable for the crimes they had committed. There were temples like Saturn's where these patients were cared for through bathing and music.

In Spain, the monks of the Order of Mercy, influenced and impressed by the care with which the Arabs took care of their mentally ill, founded in various cities such as Valencia in 1409, the “Houses of the Crazy” or “Houses of the Innocent”.

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, psychic illnesses were also seen as revelations of divine fury.

At that time, religiosity overlapped the observation of the studied phenomena. It was the case of Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430) who dedicated himself to the observation of memory and conscience. However, his devotion did not allow his observations to contradict the supernatural conception of psychic diseases.

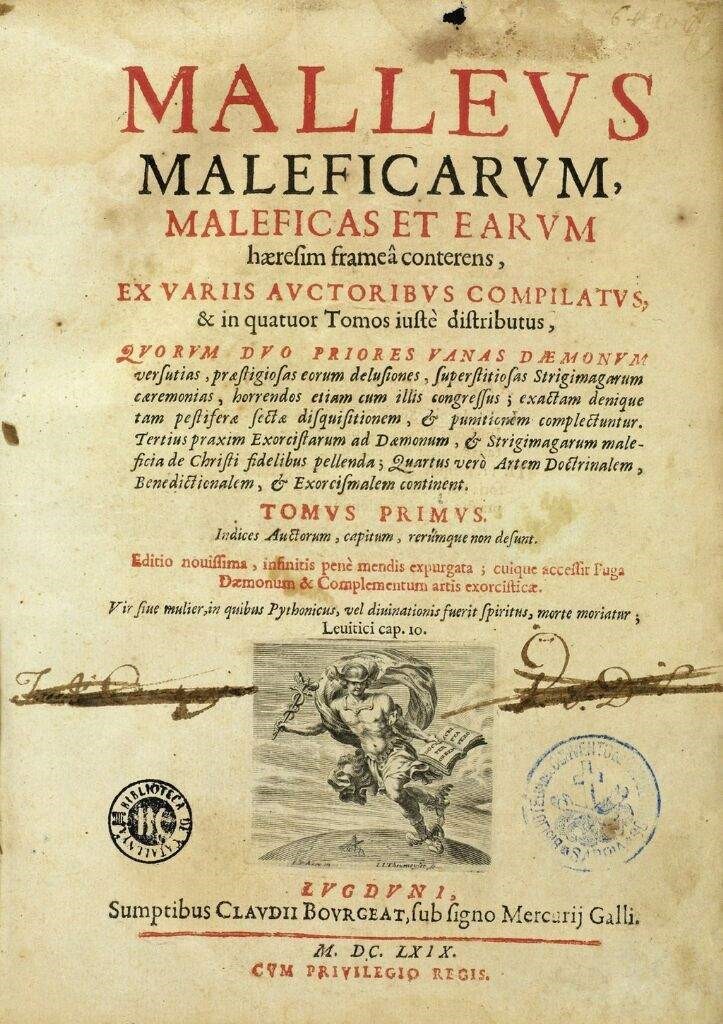

In Europe during the Middle Ages and until the end of the 13th century, it was believed that mental illnesses were related to witchcraft and those who suffered from them were placed on the margins of society, kept in isolation or even killed. At that time, the treatment was based on exorcisms so that the body could free itself from evil spirits. In 1484, the book Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) written by two Franciscan priests was published, where they described how witchcraft was identified, how demons intervened in witches and how they should be judged and punished.

At the time, when the church had enormous power and the intention was to eradicate the majority of diseases, a witch hunt began, that is, all women who behaved differently were hunted and killed.

Although the Arabs founded the first hospital for the mentally ill in the city of Fez in 700, it was not until the end of the first millennium that the first “asylums” or hospitals for this type of patients appeared in Europe. The first to be built were in the colony of Geel, Belgium in 850 and the Bethlem Royal Hospital in London in 1247.

However, the purpose of these asylums has degraded. The mentally ill, abandoned by their families, began to be taken to hospices and charitable institutions where they also housed criminals. The conditions were terrible, all inmates were subject to the same rules of surveillance and repression. They were subjected to food abstinence, corporal flagellation and the most violent and dangerous patients were chained to the walls or the floor. On a certain day of the week, they were placed in cages, as if they were animals, and were admired and incited with long sticks by the public who had free entry.

Over the centuries and until the end of the 16th century, there was no development with regard to the treatment of patients with mental illness. On the contrary, there was an intensification in practices of disrespect, persecution and survival conditions.

Existing hospitals continued to house individuals who were marginalized from society, including those who suffered from mental illness or madness, as they were called at that time.

Regardless of this stagnation, however, there were some advances promoted by studies in the field of psychology carried out by Saint Thomas of Aquinas.

Paracelsus (1493-1541) stated that mental illness was a disturbance of the body and this in turn was linked to the subject's soul.

Dutch physician Johann Weyer (1515-1588), in his book “De Praestigiis Daemonum et Incantationibus ac Venificiis” (On the Tricks of Demons), also assumed that mental illnesses were not supernatural and that witches needed to be treated as mentally ill”.

Several studies were carried out by Robert Burton on mental disorders and the understanding of depressive states; Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) studied the classification of hysteria, hypochondria and nervousness symptoms and Johann Langermann researched the psychosomatic reasons for illness. Anatomist and neurologist Thomas Willis (1621-1675), in addition to studying general paralysis, described the clinical condition that came to be called schizophrenia.

In the 17th century, there was a greater interest in the scientific interpretation of "diseases of the spirit". Copernicus, Da Vinci, Galileo, Descartes and Newton revolutionized the natural sciences and human thought.

Madness was taken as a theme in several poetic works, such as Shakespeare's Hamlet and King Lear, Erasmus's In Praise of Folly and Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote.

Patients continued to be marginalized. In France, under the 1656 edict published by Louis XIV (1643-1715) to reduce begging, vagrancy and establish order and discipline in public spaces, the Hôpital-Général des Pauvres was created, known as the Paris General Hospital, consisting of several distinct buildings, including:

Bicêtre – for poor male: the old, children, paralyzed and scrofulous persons, the epileptic insane, and those imprisoned by royal order;

and

Salpêtrière – especially for women: children, the old, weak, blind, mad, paralyzed, convicted prisoners, prostitutes, and pregnant women.

Due to the political and social reforms that took place at the end of the 18th century as a result of the Enlightenment ideals and the French Revolution, new practices were established with regard to the mentally ill. The poor, the old and the stray were removed from the asylums, leaving only those considered to be crazy.

Medicine at the end of the 18th century began to distinguish and identify the differentiated behaviours of patients through the study carried out by Philippe Pinel, in France, when he began to classify patients, disassociating those who suffered from social deviations from other diseases. The mentally ill began to enjoy a new specialty, psychiatric care and a new concept, and started to be called "alienated" and to be assisted in the asylum hospital.

Both Philippe Pinel and his disciple Esquirol (1772-1840) in France and Daniel Tuke in England are considered the main innovators regarding the asylum reform movement, with the internment aspect being replaced by the medical one. Mental patients began to be subject to uninterrupted social and moral control, to enjoy a rational environment, to be watched, judged, held accountable, corrected, and repressed.

For Pinel, the connection between the institution's classifications, mental illnesses and the relationship between the health professional and the patient, moral treatment, that is, a power, knowledge and place for its exercise, the hospital, were fundamental. Considered to be the innovator of alienist science, he tried to observe the course of mental disorders, signs and symptoms and where they affected the patient's organism. He is also regarded to be the first formulator of alienist science, which meant observing the natural course of mental disorders, directing attention to the signs and symptoms of madness and identifying where they affected the body.

In the eighteenth century, there were also several studies, research and published works on psychic illnesses.

Albrecht von Haller looked at the sensitivity of the nervous system, irritability and muscle contractions. Pierre Cabanis researched the theories from a psychological and somatic point of view. In 1799, he published the Traité du Physique et du Moral de l´Homme where he explained how moral phenomena become physiological.

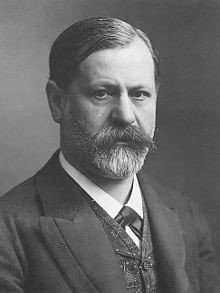

In the 19th century, several physicians researched various mental illnesses, their factors and the means of regressing such illnesses. They sought to relate these diseases to hereditary degenerative factors. The identification of schizophrenia researched the effects of drugs on behavioural changes and how some disorders could be cured through hypnosis. Thanks to Freud, the development of psychoanalytic theory and the study of the treatment of neurosis were achieved.

In the twentieth century, there was an attempt to treat schizophrenia using malariotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy and insulin therapy.

With the development of psychopharmacology, there was better treatment through the combination of psychotherapy and drugs from the first half of the last century. There were several drugs used for psychiatric treatments such as lithium, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, imipramine, amphetamines, and methylphenidate, the latter being already used in the last two decades of the century.

Some figures in history are known to have suffered from depressive states like Saul, the first king of Israel, who supposedly was possessed by an evil spirit. To alleviate the symptoms, he asked David, his successor, to play the harp.

Roman emperors Caligula and Nero, as well as Ukrainian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, suffered from schizophrenia.

The king of France, Charles VI, called Charles the Mad, had his first outbreak of madness when it seemed to him that he had heard a spear buzz that would probably kill him. As a result, he killed five of his soldiers. He, also delirious, threw fire objects and made his physiological needs in his clothes. He believed he was made of glass and "inserted small iron rods in his clothes to prevent him from breaking into pieces". Doctors subjected him to various treatments such as brain drainage, exorcism and scares, but with no results.

Painter Van Gogh also suffered from mood swings. There is a reference that he suffered from “epileptic seizures” as a result of drinking beverages containing absinthe, a substance that was used to modify brain activity and thus “stimulate” artistic activities. Currently, it is believed that he suffered from Bipolar Mood Disorder, according to "depressed conditions, alternating between euphoric (or manic) episodes that made him plunge into a mood of great energy and passion". Van Gogh committed suicide at the age of 37.

In the history of Portugal, there were several cases of royal figures who had no interest in politics. The greatest example was Queen D. Maria I, mother of King D. João VI. Her illness was certainly a consequence of her religious character and of the death of her husband and son. She had demonic visions, an exaggerated fear of crucifixes, ate only one type of dish, and uttered insults to the people around her. Although she was seen by an English doctor, no benefit for her at all came out of it.

It was not until the middle of the 18th century that psychiatry (Psyché-Yatros) was considered a medical science due to the progress and studies carried out by Pinel.

With the liberalization and acquisition of human rights, the clarification, the dissemination of new ideas and civil liberties gave rise to the mentally ill beginning to be better understood. Their treatment by health professionals became closer, more sympathetic and understanding.

Patients who, at first, had been forcibly or unwillingly isolated in asylums, were now moved to hospitals that were first closed and later opened. With this new modality, patients could go out for consultations or even be on an outpatient basis and live with their families. The acts of manipulation and punishment to which they had been previously subjected, were now replaced by greater freedom of spirit despite their disturbances. Mad people now had sick status.

It was at great cost and only half a century later that the Enlightenment and Humanist currents, which had emerged after the French Revolution, and the new medical knowledge arrived in our country. Portugal followed European development very slowly.

One of the consequences of these new ideals, which took over all of Europe in the 18th century, took place in Portugal in 1872 when the University of Coimbra was subjected to a reform ordered by the Marquis of Pombal and undertaken by Ribeiro Sanches, leading to the transformation of the Surgery Schools in Lisbon and Porto into Medical-Surgical Schools.

It is known that since 1539, in the Todos os Santos Hospital (located in the current Praça da Figueira, whose facade faced Rossio) “the sick outside their wisdom”, who wandered from infirmary to infirmary or were confined in dungeons, were cured. After this hospital was badly damaged by the fires that occurred in 1601 and 1750, it was rebuilt in 1761, and the S. João de Deus infirmary was created.

In 1775, due to the knowledge of the decay conditions in which the patients survived, they were transferred to the S. Teotónio (male) and Santa Eufémia (female) wards at the São José Hospital.

However, despite all efforts, the situation experienced at São José Hospital was truly decadent. In addition to the fact that doctors had no knowledge of the most recent specialties, financial difficulties and the decline in facilities led to inhuman degradation in the care and treatment of patients.

In the middle of the 19th century, among the clinicians at S. José Hospital, Dr Joaquim Bizarro stood out, showing his interest in alleviating the diseases of the alienated and publishing the first statistic based on Pinel’s classification.

The situation in which the alienated lived was so humiliating and embarrassing that there were several interventions to change this scenario.

In order to improve the conditions of the alienated in Portugal, António de Sampaio and his son Osborne Sampaio, who knew the enormous progress in England in this area, contributed with the valuable amount of 20 contos de réis for the construction of a new hospital.

General Saldanha, after the Maria da Fonte Revolution (popular revolt in the spring of 1846), also pushed Queen D. Maria II to found a hospice for these patients.

Between 1840 and 1848, several meetings were held at the Society of Medical Sciences in order to highlight the role of doctors in creating a favourable and accepting climate for the sick and the medical guidance to be adopted. Bernardino António Gomes, António Maria Ribeiro, Martins Pulido, Guilherme Abranches, Caetano Beirão, Magalhães Coutinho, and António Gomes distinguished themselves in these sessions.

Bernardino António Gomes, Filho, (1806-1877), was a naval doctor since 1841. He revolutionized anaesthesia techniques and was the first Portuguese doctor to use chloroform and an ether inhalation device. He was director of the Navy Hospital and was very interested in the insane hospitalized in the institution.

He also criticized the lack of proper asylums for mental patients and how they were treated in hospitals in the main cities of the country. He also said that the places destined for the alienated were more like a shelter for beasts or a dump for useless waste and pointed out the degrading conditions in which the patients lived, in a dark cubicle with poor hygiene.

At first, the government suggested using the Luz building (where the Military College was later established). However, this option was the subject of discussions, criticisms and opinions.

At a time when liberalism was in force (after the extinction of religious orders in Portugal) and when it was customary to take advantage of existing monasteries to function as public institutions, the former S. Vicente de Paulo monastery was used to set up the Rilhafoles Hospital. This new hospital, the first to be founded in Portugal with the sole purpose of housing and treating the alienated, opened on 13 December 1848.

Francisco Pulido was its first director and, between 1850 and 1851, made a detailed report on the Rilhafoles Alienated Hospital, which became known as the “lunatic asylum”.

In this work, he mentioned the existence of 350 beds when there were already 1708 patients. However, it was known that this number was much lower compared to what existed in reality. On the other hand, it was known that the rate of people with mental illness was lower in the interior of the country and among married people.

However, there were many difficulties at Rilhafoles Hospital, although there were several criteria for hospitalization. Curable patients were given occupations, instruction, recreation and above all bathing in the sea. Although they tried to follow Pinel's rules with the alienated being treated with delicacy, vigilance and cleanliness, Rilhafoles Hospital did not maintain the progress achieved initially.

Dissatisfied with the results obtained, Francisco Pulido left the board and was replaced by Guilherme Abranches, who immediately opposed the Hospital's overcrowding and decay. He submitted patients to various treatments such as bleeding and balneotherapy. This procedure, which had great prominence at the time, became famous as the Rilhafoles spa, inaugurated by Queen D. Maria II.

As in Lisbon, in Porto the resources to treat the alienated were non-existent. Patients were delivered to the Santo António Hospital called “Porão” (Hold).

The first building constructed for this purpose was the Conde Ferreira Hospital, through the legacy of the meritorious Conde Ferreira and inaugurated in 1882 by the professor from Coimbra António Maria de Sena.

António Sena was considered to be the first great Portuguese psychiatrist and part of the great innovators in psychiatric care and mental illness. He was very interested in legislation and legal protection for the sick and in humanitarian care, hygiene assistance, and the education of medical and nursing staff.

He published a profound study on the assistance to the alienated from a medical-social perspective. He also carried out statistics on existing mental patients.

He was director of the Conde Ferreira Hospital between 1883 and 1890, where he campaigned in favour of assistance and the regulation of innovative services. In 4 years, 102 patients were cured.

He had Magalhães Lemos as aiding physician and Júlio de Matos as assistant physician, who succeeded him as director of the Hospital between 1890 and 1911. This year Júlio de Matos succeeded Miguel Bombarda in the board of Rilhafoles Hospital and his assistant Magalhães Lemos was appointed director of the Porto Hospital in 1911, holding the position until 1924.

From 1892 onwards, there was a huge decline both in the treatment of the alienated and in the organization of the Rilhafoles Hospital. However, it ´progressed thanks to the unique personality of Miguel Bombarda. In a diligent and methodical manner, he was appointed director of the Rilhafoles Hospital that year. Soon he started a real remodelling both in the organization, in the therapeutic management and in the scientific study of Psychiatry. He published numerous and varied works as well as several reports on the Hospital service the that he had known so well since his time as a student. He abolished various hospital procedures, such as the use of strong chairs or bed arrests. Miguel Bombarda was very interested in medical prophylaxis because he considered that assistance, teaching and research should exist in hospital organization

From the last decade of the 19th century, there was enormous progress in Portuguese psychiatry thanks to both the liberal and entrepreneurial spirit of António Sena, the dynamic and disciplined personality of Miguel Bombarda and the introduction, from 1911, of the teaching of psychiatry in the official medical studies syllabus.

Years later, on 2 April 1942, the asylum in\Campo Grande was inaugurated, named Júlio de Matos Hospital, considered one of the best in Europe.

António Flores, its first director, had a perceptive character, and gave a new orientation to hospital activities, both in the clinical and in the scientific fields, originating an authentic revolution in psychiatry, with renewed assistance, therapeutic, scientific and pedagogical actions. Patients acquired new rights but also more responsibilities and obligations.

Years later, Professor Egas Moniz (1874-1955), a notable physician and scientist, stood out mainly in the areas of Neurology and Neurosurgery, having been responsible for the invention of cerebral arteriography or angiography and leucotomy. With this invention, he was awarded, in 1949, the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology, the only Portuguese receiving this distinction to this day.

Although Egas Moniz had possibly treated mental patients, Egas Moniz's psychiatry was purely neurological. Having as essential references Ramón Y Cajal and Pavlov, Egas Moniz believed that mental illnesses could only depend on a dysfunction of communication between neurons, that is, a dysfunction of synapses which, therefore, should be broken.

In his speech at the Medical Literary Conferences published in 1953, we quote, 'I concluded that these synapses, repeated in myriads of cells, are the organic basis of thought. Normal psychic life depends on good synaptic functioning; and mental disorders result from the breakdown of synapses’.

On the Nobel Prize website one reads: The Nobel prize (1949) to: ANTONIO CAETANO DE ABREU FREIRE EGAS MONIZ for his discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy in certain psychoses.

At a time when there were still no effective psychotropic drugs for the treatment of serious mental illnesses, leucotomy (a surgical intervention to interrupt communication between two brain areas that are very important for emotional control) was a very important therapeutic advance. Egas Moniz was very restricted in the cases when he used this therapy, which was used by others in other countries without criteria with very negative consequences, but this fact does not detract from the discovery itself. Currently, psychotropic drugs have come to dethrone, and well, psychosurgery as Egas Moniz conceived it. Coincidentally, psychopharmaceuticals also target the functioning of synapses, evidently with great advantage over psychosurgery because it is a reversible intervention, but the concept itself - mental illness resulting from altered synaptic functioning - was a finding by Egas Moniz from the little evidence that existed at the time.

We can, therefore, conclude that Egas Moniz returned to Hippocrates' thought, integrating it in the light of knowledge only obtained in the 20th century - the identification of neurons and synapses - inferring their importance to intervene on mental illness. He was not the only one, as in science no one will be unique, but he was the first to demonstrate the therapeutic value of this knowledge when it was necessary to mitigate the consequences of mental illness in individuals whose alternative, at the time, was often just a straitjacket.

Thank you note:

We thank Professor Ana Maria Sebastião for her support in the analysis, review and suggestions in the writing of this article.

References:

Castelo Branco, M.L.B. (1960). Um século de psiquiatria em Portugal. Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon.

Jara, J.M. (2007). Contribuição para um livro branco da psiquiatria e da saúde mental em Portugal. Sep. Revista de Psiquiatria do Hospital Júlio de Matos. Lisbon, March 2007, pp. 1-26.

Pichot, P. and Fernandes, B. (1984). Um século de psiquiatria e a psiquiatria em Portugal. Roche. Lisbon.

Historia da psiquiatria no Brasil e no mundo

https://www.cursosaprendiz.com.br/historia-psiquiatria-brasil-mundo/

História da psiquiatria

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hist%C3%B3ria_da_psiquiatria

Lurdes Barata

Library and Information Unit

Editorial Team