We had arranged this interview some time ago when I expressed an interest in attending a Temporomandibular Joint intervention. I was far from imagining the diversity of clinical answers that I would find through Prof. Dr. David Ângelo.

When I got to the interview, I found a waiting room that could easily be a 5-star hotel room, in the heart of Lisbon. There was nothing hotel-like about it, just the view from the 5th floor straight to the Sheraton. Velvet sofas of an aqua-green blue and the smell of aromas that could have come out of a broken bottle of the best scent ever. The decoration was meticulously thought out, as were the uniforms of the team from the private Institute, where David Ângelo shares a partnership with the Spanish doctor David Sanz.

It was during a maxillofacial surgery internship in Coimbra that the two met and soon became friends. From that time onwards, every time one of them performed private surgery challenged the other to participate in it. It was in this dynamic between the two that they realised the need to create a centre specialising in facial treatments in Portugal. From the early days, when they had a small, rented office in Parque das Nações, and travelled the country from north to south to perform surgeries, a more ambitious and consolidated project was born, with more than 350 certified evaluations on Google Reviews, with 5 stars, perhaps the result of their permanent concern for their patients.

As I wait for David Angelo, I hear a group of people in a good mood, patients, and staff; it felt like we were in a house with familiar people. Our interview started on time, everything planned to the minute. David Angelo appeared in the waiting room. He had the same rigorous medical uniform that all his team displayed beforehand. First, we were given a guided tour of the Institute, where I realised that nothing gets mixed up and everything works at the same time. Two young women at the reception desk carefully welcomed those who arrived, an office where only treatment plans are discussed, a clinical meeting room and an area dedicated to administrative management, which manages the agendas and supports the communication of doctors, a properly equipped nursing room, a space for physiotherapy and speech therapy, an office for the management of surgical patients and a mini studio. In fact, a photographic studio with tripods and cameras that allow the capture of images of each patient with great rigour, following a protocol, from the first day they enter, and their evolution throughout their treatments. The medical cabinets side by side.

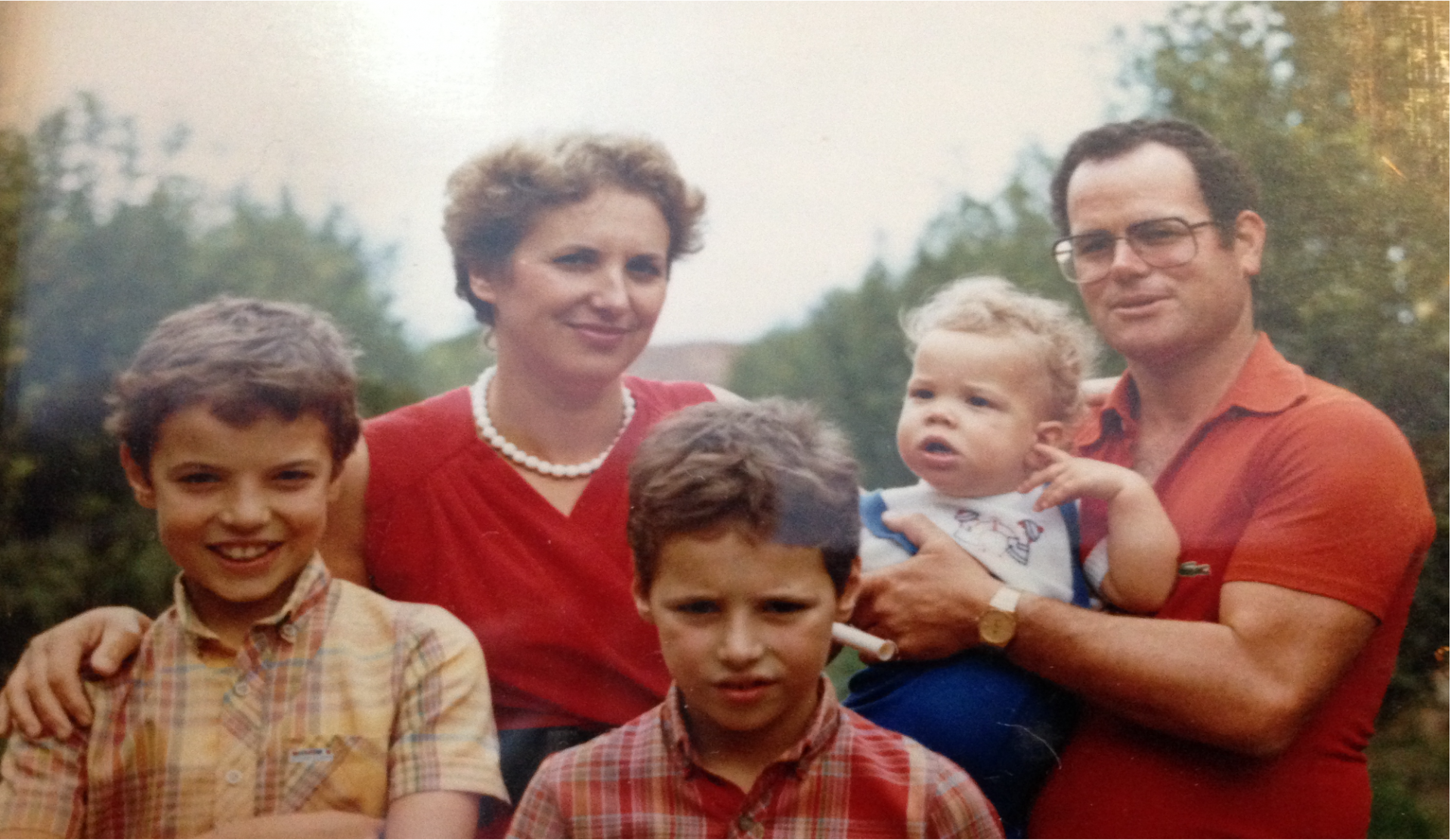

Always communicative and confident, we entered his office, where there seems to be no more room on the walls, full of news published about him or his diplomas. For the first time there is an obvious mix of the professional and the personal, through the countless photographs that give me a glimpse of a solid bond with his parents and 10-month-old Caetana, David Ângelo's daughter. Before starting the interview, he explains that he gives great importance to social networks, and that nowadays it is necessary to adapt communication to the habits of the population. A record holder for likes and views on social networks, he communicates scientific and academic content and some of his personal life in a balanced way.

"You wouldn't believe how many patients come to my appointment and ask about my dog, my daughter, my parents – when they come in, they feel they already know me and that's fantastic, it helps strengthen the doctor-patient relationship." David Ângelo may have this relaxed image on social networks but don't be fooled, he has an enviable academic CV: he has received more than 11 national and international research awards, has dozens of articles published as first author in the best journals in the speciality, and as well as teaching at the Faculty of Medicine, he is the main face of the post-graduate course in open surgery and arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint at the same Faculty. He performs unprecedented surgeries in Portugal using techniques developed by him.

After the initial introductions, we started the interview. Little did I know that I was going to have a private lesson on TMJ pathology before the intervention started. While the patient who was going to be operated on was with her nurse in a separate room watching a video of the operation, taking blood, and reinforcing post-intervention care, I was starting my first lesson on TMJ pathology.

In the family photo we could see David Ângelo at the age of two, with very fair hair, already pointing to the Temporomandibular Joint. The youngest of three brothers, he was born in Switzerland and lived in several places until he started his medical course in Covilhã.

He explains that "the pathology of the Temporomandibular Joint is extremely important because it has a high prevalence, in some countries it can affect 46% of the total population". There follows a series of images of the articular anatomy, where it can be seen that the joint is very close to the ear. This proximity is one of the reasons why joint pain is easily confused with ear pain, leading patients to an otorhinolaryngology consultation, thinking that the problem is in the ears, when in some cases it is related to the joint. "Everything has an explanation from an embryological point of view," he explains as he holds up a skull and shows me the jaw area. In a few seconds I hear words that I can barely register: "pharyngeal arch, meckel's cartilage, condyle"... I realise, however, that the nervous and vascular connections between these strange elements are close. In this new personal learning journey of mine, I realise that there are dozens of muscles working together when we do something that seems as instinctive as chewing. The class continues, with direct questions from my interlocutor to me. "When you chew you have two muscles that are much more prominent. Which ones are they?". My silence continued without any sign of being broken, he resumes, without exactly waiting for my answer. "They are the temporalis muscle and the masseter muscle; these are the most important for chewing and where we find part of the problems that cause tension in the jaws". The answer appears with visible logic when he shows me a video of a patient chewing, where we can also see that clenching the teeth, one against the other, can result in a muscular contraction of the jaws, which can be associated to headaches, or contribute to earaches. "In the middle of the joint there is also a disc that cushions the chewing loads", says the professor; "and if this disc is being compressed, what will happen?” Finally, I answer with enthusiasm: "It wears out?".

This time I get it right. He confirms my answer and reinforces that the disc can wear out or move out of its usual place, like a meniscus that wears out in the knee, one of the reasons that can explain the inability of so many people to open their mouth, or that, even if they open it, they can't close it afterwards.

The class continues and shares with me images of tests done on a cadaver. "Hang on Joana and don't fall", I think and smile, being equally interested and curious to see a little bit more. We go from the cadaver video to very real clinical cases. There are several people at a very young age who have joint problems. He shows me videos of patients before surgery, where with each movement of the mouth you hear a clicking sound, like a ping-pong ball hitting endlessly; a sound that disappears as well as the pain after treatment. In our conversation, David Ângelo stresses that this is a team effort, and that all patients are always accompanied by physiotherapy and speech therapy. One detail that impressed me was that this young doctor keeps a continuous follow-up of all his patients throughout the years, recording everything in detail in a database he created – EuroTMJ. It is no coincidence that Harvard University contacted the surgeon and showed interest in being a research partner and integrating this database in its hospital. He tells me about this project with contagious enthusiasm. "Imagine the scientific impact this database could have if leading TMJ surgeons registered all their patients on this online platform?" – we could learn a lot about our treatments and improve our understanding of the pathology, surgery outcomes and most frequent complications, among other interesting findings that we can study. This database is shareable but protecting each patient's profile.

As we speak, an assistant prepares the room for the intervention. The nurse knocks on the door, the doctor gets up and goes to receive the patient. Carolina (fictitious name) comes directly from Porto and will be undergoing treatment for TMJ dysfunction. She already knew I would be in the room and had her informed consent for me to be there. David Ângelo explains to me that it is a mild case of joint dysfunction but that he has had previous treatments in other clinics with no results. He shows me the MRI scan and explains why he has indicated an arthrocentesis for the patient. This technique allows a specific washing of the joint and is then complemented with regenerative cells and hyaluronic acid – one of the pioneering techniques he has developed for TMJ.

Our theoretical lesson is over. Now the real time intervention begins. After the entire joint area has been disinfected, a local anaesthetic is administered, which can be intensified if the patient feels pain. David Ângelo explains that many doctors perform this procedure under general anaesthesia, but he prefers to do it under local anaesthesia as it is more comfortable for the patient.

The goal of this procedure is to introduce two washing portals into the joint area and remove the inflammatory cells through a washing process. The inflamed fluid is removed, and in this case, David Ângelo will send this fluid for a pioneering laboratory analysis, from another study he is developing. This is a study that could revolutionize the way TMD is treated. Another pioneer study! Waiting for this liquid for analysis is a courier, who will take the sample at the ideal temperature to the laboratory centre. Back to the procedure room, where Carolina is already installed and holding an anti-stress ball in her hand to control some of the anxiety of those awake during the procedure. The intervention is done on both sides of the face, the first one takes some time but, in view of some controlled anxiety of the patient, David Ângelo continues to do the whole procedure with the same tranquillity as always, while listening to jazz and asking for a new reinforcement of the anaesthesia. When changing the joint side, there's some anxiety so that Carolina isn't administered more anaesthetic. And the truth is that she isn't. Everything is done at the first time. From this observation I also learn that the anatomy itself can make access difficult. The doctor finishes the procedure and Carolina already has the physiotherapist waiting in another room. Everything is programmed to the minute.

While doing the report on the intervention, he explains to me that of all his patients only 13% need to resort to more invasive surgery. He manages to treat most patients with minor surgery, without general anaesthesia, as is the case of Carolina. As we change rooms, the interview continues in the kitchen area between a cup of coffee and some folar de carne (a traditional type of meat pie), offered by a patient from the north who came for a routine consultation with David Ângelo. In this more informal moment, he recalls the name of the first patient he operated on, it was someone who had had the mouth stuck about 30 times. It was a surgical success, and we gave the patient back her quality of life. He also knows the name of his greatest frustration, a 19 year old girl, who after severe radiotherapy developed deafness and a severe limitation in opening her mouth. She can barely open her mouth and is fed through a straw. David Ângelo tells me he has taken this case to numerous international conferences, talking about the case of this Portuguese woman to whom he wanted to offer a surgery, but the truth is that he can't solve the problem. And neither can the world. He's been advised by leading specialists not to operate on the patient, because there could be serious complications.

It was at this precise moment that he received a phone call from an Italian colleague, with whom he spoke in English. He is a man of the world, his life shows this well, he was born in Switzerland, at a time when his parents were emigrants. He also lived on the island of Madeira and in Luxembourg, before entering the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Beira Interior in Covilhã.

Eleven years ago, when he first became interested in this area, TMD was little talked about in Portugal. There were several specialities that patients sought out, most of the time with no response. This was the reason that led David to leave Portugal to learn more about this area. When he returned, he came back with a different vision of the possible treatments for these patients. He began to implement new treatments, many of them minimally invasive. With a tremendous level of technical demand, to know how to perform a surgery one needs a lot of practice, especially if we are talking about TMJ arthroscopy. This is why he decided to become a TMJ surgeon only, in order to have a good surgical casuistry, in a very complex technique: "If I stay 1-2 months without operating, I immediately notice the difference in my surgical skill". I need to operate all the time to evolve, it's amazing. In other techniques I don't feel that, but in arthroscopy I feel that need". It is not by chance that in Portugal he is the only one doing advanced arthroscopy, where you can suture the disc, and in Europe there will be less than 5 people with that surgical level. "It's a life commitment with this small joint", he says. David Ângelo receives doctors from all over the world to do internships with him at the Institute (Sweden, Malta and Romania are some of the countries from which he has received doctors).

He likes to control his own life, even when his goals are frustrated by the greater will of what is said to be fate. Whether it's straight ahead, or in twists and turns, the 36-year-old doctor takes his will very seriously and doesn't give up easily. While we go to see the patient he treated and who is now in physiotherapy, he tells me that this pathology is often undervalued and underdiagnosed. He himself admits that recently he was tempted, on hearing his mother complaining about an ear infection, to ask an otolaryngologist for help. It was from there that the warning came, there was a problem with the temporomandibular joint. His mother did indeed have a perforation of the articular meniscus, which forced him to take his mother to the operating theatre.

There is much more to tell about the inspiring stories of this young doctor, who seems to adapt to any environment. He told me that he worked his way up from the simple to the more sophisticated, but "without any delusions". He never ceased to be a learner of life and to know how to be in the various social settings, from the humblest to the most sophisticated.

As he tells me, it was research that tamed his rebelliousness and it would be during his doctoral phase, at the age of 27, that he would change his behaviour to someone with rules and responsibility. In conclusion, he admits that professionally he would like to be brilliant in three areas: in the clinic, in research and in academia. But he recognises that it is very difficult. He manages to exercise clinical and surgical activity from 8am to 6pm, to take on a family role, and the rest of the little time he has is divided between teaching and research. For all that time he invents more time. He loves travelling to Porto by train, with a scheduled departure time of 6.36am, which allows him to focus on research and study until he reaches his destination. He applied the same principle a few weeks ago when he travelled 18 hours by plane to San Diego, where he was the only Portuguese member of the American Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons. Success seems natural to him, but he likes to reinforce that people only see the tip of the iceberg – "there are many failures behind the success".

The expectations of those who sit in front of this surgeon are great, but the solution may or may not exist, and its effectiveness also depends on factors that not even a doctor can control alone.

What was it like to operate on your own mother?

David Ângelo: Foi muito difícil. Andei a adiar a decisão de ser eu a operar, mas a verdade é que em Portugal havia poucas alternativas. E fora do país, como estávamos em plena pandemia, não queria arriscar. Quando chegou o dia, preferi não assistir à parte da indução anestésica. Chamaram-me quando já estava a dormir. Entrei no bloco operatório e foquei-me no que tinha a fazer. Nessa altura deixamos de pensar no que nos rodeia, ali há minha frente estava um doente que precisava de mim.

What was it like taking your own mother to the OR for surgery for you?

David Ângelo:It was very difficult. I put off the decision to operate, but the truth is that in Portugal there were few alternatives. And abroad, as we were in the middle of a pandemic, I didn't want to risk it. When the day came, I preferred not to attend the induction of anaesthesia. They called me when she was already asleep. I went into the operating theatre and focused on what I had to do. At that point you stop thinking about your surroundings, there in front of me was a patient who needed me.

Was your mother nervous for you?

David Angelo: She was. Do you believe she wrote a letter, in case she died in surgery? In that letter she rested me and asked me not to be traumatised and not to stop practising medicine. It was a very emotional moment when we both cried!

You told me that you don't always live up to people's expectations and that things don't always turn out the way you want them to?

David Ângelo: Yes, there are variables that we don't control. It can happen that the surgery is technically a great success, but the patient still has complaints. Fortunately, it's rare, we have an overall success rate of around 87%.

Which is already huge.

David Ângelo: It's huge but there's still 13% to go. These are people who put all their trust in that intervention and in me. When they don't get better, I feel bad. We still have a lot to learn about pain mechanisms. I always remember the cases that don't go so well. I always continue to follow them up and look for solutions to improve success rates.

And what explains the 13% failure rate?

David Ângelo: There are many variables that we still don't understand. I'll give you an excellent example of an article I was reading today on the somatisation of pain in patients undergoing surgery. In that study they observe that patients with depression, fibromyalgia and a higher anxiety index are patients with a higher risk of failure in the TMJ procedure. I have already concluded the same thing, in a publication that I did recently, which points out these patients as a risk group. The truth is that the mind controls a lot of these events and conditions the actions around them. The more negative people are more pessimistic, and this interferes with the result. However, this patient profile also deserves to be treated. I cannot simply refuse to treat these patients. What I do is that, faced with this patient profile, I explain that they have a greater risk of not having such satisfactory results. They generally accept and want to try the intervention anyway.

What causes people to have TMD?

David Ângelo: There are several causes: micro or macro trauma, anxiety, increased intra-articular pressure, autoimmune diseases, among others we still don't know about.

Are there patients that keep you up at night?

David Ângelo: There are. There are cases where I don't sleep well the night before surgery. I go over all the steps so that the surgery is flawless. Usually in very complex surgeries, which have more than 250 different sequential steps; you must memorize each one of those steps so that everything goes well.

And what about the relationship between the doctor and the patient, even when the doctor hasn't saved his patient in the way that was expected?

David Ângelo: (Points to a doll with a small dog) Do you see that doll? That's me. A patient gave it to me. I've operated on her three times, and the first time was not a success. Neither I nor any doctor performs surgery to be unsuccessful, but the truth is that failure is part of our life, and we must not forget it. Failure is tiring and makes us feel exhausted, but it is part of being a doctor. Patients understand that we do our best to help them and that is important.

How has your international integration been achieved? You are the only Portuguese doctor to belong to the American Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons.

David Ângelo: It was through the scientific articles that I was and am publishing. My former Director, Professor Francisco Salvado, used to say something to me that I never forgot: "If you don't publish, you don't exist". It is true. I can do the best treatments in the world and have the best results in the world, but if I don't publish them in any magazine, I can't have visibility? If no one knows my work and what I do, how can I expand my research and help Portugal develop this area? My publications are the reason for my international recognition at a relevant level. I have a good characteristic, I am a maker, I finish my goals. Einstein said that "a good idea without an action plan is nothing but a hallucination". This is true and I have that action plan for everything, and I really follow it. I think that new generations find it difficult to move forward because they have many ideas, but they don't put them into practice. Making it happen takes a lot of work. When I have an idea for a research project I start writing and I set deadlines, which I make an effort to meet. The students at the FMUL, where I coordinate the master’s theses, are surprised because in the first meeting we make a schedule that even includes the day of the presentation. Of course, there may be delays, but this schedule serves to create a commitment to the project. I once took almost two years to prepare a paper.

For someone who plans everything so meticulously, tell me, doesn't life sometimes change your plans? Can you always keep everything under control in your life?

David Ângelo: It does, it does. In terms of research, it changes a lot. I'll give you an example. When I began my doctorate project I'd planned to operate on sheep, on floor 9 of Santa Maria Hospital, in experimental surgery. Shortly after, I received a letter from the ethics commission saying that that biotery was not certified by the DGAV and that I couldn't operate the animals there. In other words, all my work was back to square one. Everything collapsed, I couldn't do anything else. I went looking for solutions. Do you know what I did?

I rebuilt a shed my parents owned and built an biotery from scratch. And now even some important names in the hospital area ask me to go and operate sheep there. This facility is obviously certified by the DGAV. It was the only way I could continue my animal research. It was there that I applied the ten thousand euros I won from a grant for a young researcher in Pain area. The rest of the money that I saved was used in the biotery.

Has the research also changed you plans? I mean, is it common for a paper to be submitted and then be rejected?

David Ângelo: I'm resilient, you know? I had a paper that was submitted to 16 different journals, only the 16th time it was accepted. I never gave up, you know why? Each time it went back, I corrected it and learned something more, because it brought valuable comments from the reviewers and that helped me to improve. Finally, I managed to publish in the International Journal of Surgery, whose impact factor was almost 6. (The impact factor of a scientific journal is one of the most important elements to define the credibility and quality of a journal and its articles).

Is it possible to regenerate the disc?

David Ângelo: Not yet. In my studies I was able to prevent an osteoarthritis process after removing the disc. After removing the articular disc, I would like to create a solution to replace it, but I can't afford it on my own, you need big funding from industry to support these projects.

Joana Sousa

Editorial Team