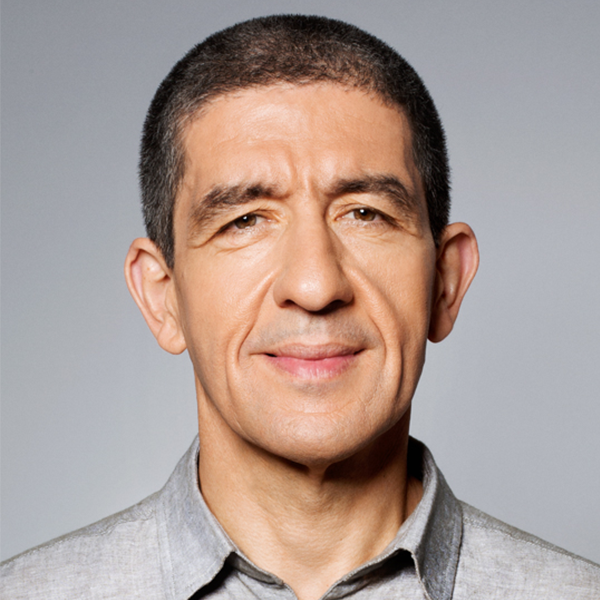

"I just hope that they are unaware that I am also here". He referred to himself about having joined the group that set up the João Lobo Antunes Institute of Molecular Medicine (iMM). The phrase translates well his low profile. He could be Anglo-Saxon, but he is not. From England he brought much of the intellectual and scientific heritage that we will return to as a theme.

With a sharp humour, he intersperses the most serious subjects with anecdotes, or small ironies for those who are more attentive. He is generous in the regard he has for others, which enhances his strong personality.

I looked for Domingos Henrique because he is one of the members of the Scientific Committee of the PD-CAML, and guides the new Ph.D. students.

I was striking in my first contact, “Good afternoon Professor Domingues Henrique”, and he immediately showed his sense of humour that unblocks any communication obstacle, “This starts badly... neither am Domingues, nor Professor ... I am Domingos, only. Every day, even on Sundays (joke to unwind...)”.

With this introduction, we were ready to talk openly.

A scientist by nature, he currently observes the human species as their tutor, but the Laboratory no longer seduces him, not to the point of grabbing him again under the microscope. Throughout the conversation, one understands why.

He studied at the Faculty of Pharmacy, his top grades led him to be invited to the Gulbenkian Institute (IGC) for a summer internship in 1984. He starts laughing and tells me that looking back now, "he was already old, but hadn't noticed yet."

He did his Ph.D. in Molecular Biology at the IGC, and since then Régio's poem, "I do not know where I am going, but I know I am not going that way" fits him like a glove. He chose to try a different path without being linked to the University, through scholarships, so as not to feel too attached to anything. Throughout his Ph.D., this showed him how challenging it was to live without financial support, a reality current scientists know only too well.

He then lived 6 years in England, at the time under Tony Blair's government. He got there in 1991 and opened up to the world. Then he got to know several people. Especially their experience and wisdom. It was also one of the periods when he travelled the most, both between knowledge and between European countries. He did internships and exchanged experiences, something that he recalls now with bright eyes. "That was another world, at that time there were only 3 or 4 major annual seminars attended by all the big names in Science, now there are seminars almost every day".

In England, he dedicated himself to embryology and he easily sums up the magic of Science: "if you place a chicken egg, like those we buy on the market, in a greenhouse at 37-38ºC, for 21 days and without any external intervention, we will see a chick emerge from it. Everything is there, it is like the hand that draws itself! ". “The embryo makes itself”, he continues, and understanding all the pieces and how they are assembled, is actually talking about decoding the DNA code and how it is put into practice. Understanding the embryology of the nervous system may, for example, reveal clues to better understand the human brain itself. He always saw beauty in the embryo, considering that there was no laboratory artefact in it, just a "perfect machine that works naturally". Ethics does not cross us here because the embryos that he looked at, time and time again under the microscope, were from chicken.

In these moments at the microscopic with his students, Domingos knows which one will be a future scientist, "it is the look that is different from everyone else". He speaks with magic, despite reminding me that “magic is the great capacity to catch the other person distracted”, nothing more than that. When it comes to the magic of bubbling responses, he does admit that there is magic in Science, because "the Scientist has moments of revelation when everything he has been doing for years comes together".

Back in Portugal, where he returned in 1997, he joined the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon. He joined a group of scientists who constituted one of the scientific units of FMUL, led by Professor David Ferreira, and actively participated in the creation of the iMM, a process led by Professor João Lobo Antunes. From the initial structure that still belonged to the Faculty, inside Santa Maria Hospital, its research laboratory moved to the newest Faculty wing, the Egas Moniz Building. Floor 3, as we know it today. It had Domingos' organizational finger, in close work with the building's architects.

Among the various ideas that flow in his mind, he tells stories imbued with an intelligent, subtle humour. I laugh out loud during the almost two hours of conversation, but I dare not commit any more un-confidentialities about his humour.

Today, Domingos Henrique is proud to see the success numbers of the CAML Doctoral Programme (PD-CAML), always emphasizing the prestige of the Ph.D. works. However, he admits that they want to consolidate the support to students. "They are responsible for much of the activity of the research laboratories and without them the projects would not advance", he points out.

The conversation addresses several topics, an agile game of ping pong that jumps from reflection to reflection. Shortly after we started introducing ourselves in the interview, we talked about scientific publications and the cost of publishing in the journal Nature, or in Science. I ask rhetorically if we will all have a price then. None of us replies, but as we gain space in the conversation, we realize that yes, we all have a price and the price may be moral, but it also has consequences.

He speaks very seriously about various topics, but approaches them with a refined, almost distracted attitude. The democratization of Science is perhaps one of the topics that makes him laugh out of sarcasm the most.

In 1995, he also published papers in Nature. We continue to talk about the perversion of the big global markets, which have made profit outweigh pure and hard merit. Is this analysis done by my interlocutor? No. My analysis, after I heard about it and investigated the topic. The explanation is as interesting as it is diabolical and is perhaps due to Robert Maxwell. Founder of Pergamon Press, the entity responsible for publishing scientific articles, Maxwell created one of the most profitable businesses of all time.

It is published, but to have the paper published one needs to pay. And if the author wants to revise his article, he also pays for each new access to his original. Universities, on the other hand, pay huge annual fees to promote the authors of the articles, which will give the Institutions the prestige they need.

The present times seem to dictate that to be a great scientist, the journal where he published matters more than the exact content of the article.

Science, as well as society, live in cycles that sometimes will always be disruptive, he comments, they need to be so to cool off, "it is like rock from the time of the Genesis band that with time became too classic, and needed punk to tear everything up again".

Passionate about photography, he admits that he has adapted the selfies fashion to the family, a role he says is increasingly encouraged in us. "I photographed for years and I never remembered to turn the camera on me". He shrugs and tells me another trick he used to do, at the time of the "rollex" when he was going to eat custard pastries in Belém. "The tourists asked for pictures and I took the camera upside down to take the picture; they were distressed by me turning the camera and were very disappointed to imagine themselves in a photo with the world upside down. (laughs), I told them that it was enough to turn the printed photo. It was my favourite diversion and I must have captured a lot of faces anxious to turn the world upside down...".

Another of his great escapes is running, which he balances with a meatless diet. And he does run. Culture inspires him even then, when he tells me about his philosophy towards sport, "Pain is inevitable, suffering is optional", a phrase quoted by Murakami. I go back further to observe the philosophy that Domingos has learned to apply to everything in his life, pain but without suffering. Whatever causes his soul suffering, he moves away.

For someone who was involved in the creation of the iMM structures, how do you see it 20 years later?

Domingos Henrique: The idea of creating the iMM was to streamline the scientific research that is done at FMUL, creating a dynamism that was not possible with the rigid structures that existed within the Portuguese State. Twenty years ago, something like buying reagents for research was sometimes extremely difficult. The Faculty's biomedical research was thus integrated into the iMM, which would be the Faculty's research arm. That way, research would be channelled to a single Centre at FMUL. After the creation of the statutes and with a formal announcement, iMM became an Associate Laboratory. Contests were opened for new researchers and people from all over the world began to arrive. Some are no longer here. Looking at this path, we can say, with certainty, that the iMM is a top scientific institution in Portugal.

How does one become a good scientist?

Domingos Henrique: With curiosity and a lot of love for what you do. Which is a disadvantage, because they are the most mistreated "species" for their rooting for one’s team.

Mistreated because they are poorly recognized and underpaid?

Domingos Henrique: There are many good Ph.D. students, this group is an elite that in general have had excellent academic paths. With this profile, any one of them, if they chose not to be a scientist and work for a consulting company, for example, would earn much more, probably working the same, or perhaps less. Scientists do not, most of them work with medium-value grants, without any contracts and associated benefits, until they are at least 30 or so years of age. And there is an underlying thought about doctoral students that is wrong, which assumes that "if you like studying so much, then you don't even need to be paid, you don't need help". This is one of the weakest points in the life of doctoral students. It is as if for doing what they love (studying), pleasure is a sufficient reward. However, I think that few imagine how much suffering there is during the Ph.D. Fortunately, people start talking about mental health problems in these “privileged” beings who, in fact, are not.

Can you explain this hardship?

Domingos Henrique: It starts with a clash with the reality of research and the difficulty in overcoming one of the first lessons of those who begin: to research is to fail more than to get it right. To research is to formulate and test hypotheses and it is natural that many of them are wrong and/or that the methods used are not the appropriate ones and do not allow a clear answer. Failure, therefore, is highly likely. But we have to learn to see these “failures” as steps in the right direction, which is, after all, to test the hypothesis and conclude its validity. And if we conclude that the initial hypothesis was false, this is an advance, it allows us to build other hypotheses and advance the research. If it is right, it is an advance, perhaps faster, but no less significant.

In my experience, this clash is more painful in the case of doctors starting research. Doctors are not trained to make mistakes, they have a very low error tolerance and thankfully, it means that they have had good medical training. But when they arrive at the Laboratory and start experimenting and researching, following a scientific article and trying to replicate steps and methods, they naturally start to fail. And while they learn to analyse and control all variables, they also learn that they can still fail and make mistakes again. And that's when they suffer a lot, because they question their abilities, their competences. Now, if that article gives us a certain path, then why does it fail with us? Faced with this thought, they either gain error tolerance, or they drop out.

Are there many doctoral dropouts?

Domingos Henrique: Not here at CAML. One reason is that our Faculty has a very good structure, which is the GAPIC (Office for the Support of Scientific and Technological Research), which allows medical students to go to the Laboratories and contact the reality of research, doing internships and conducting projects where they “learn to make mistakes” and acquire a vision of what it is like to do science.

Failing is a terrible thought for students who are trained not to fail, due to the job requirement…

Domingos Henrique: But it helps them a lot, it makes they understand that there is perfection, but it takes a long time to reach it. Creating permanent doubt, questioning whether we are doing well and if this is how it is done, is the best way to learn. Popper said that Science is the successive destruction of truths, and although I think that this view is too negative, it is a fact that we have to create and destroy false truths. Transposing this logic to Ph.D. students, it does not differ much, it is the way to build the necessary resilience. The capacity for criticism and self-criticism is fundamental and, since human behaviour is not widely practiced, it is useful. We don't simplify. I read a few days ago in an article in Nature how the human brain works when it has a difficulty. And the question they asked was the following: in the face of a difficulty, do people complicate, or simplify?

They complicate, don't they?

Domingos Henrique: Because they add more problems, instead of removing elements. And this is what scientist learn, to simplify..

Does one learn to relativize?

Domingos Henrique: There are always things that will not agree with the theory, but that does not invalidate the theory, it will only be a stimulus for new experiences to destroy or not to destroy the theory. This stimulus comes very much from an inner energy. (Stops slightly, as if fitting some pieces in his quick dissertation). We have a very intrinsic Catholic culture, I don't know if that influences it.

Which justifies feeling guilty about the failure. We are like that, aren't we?

Domingos Henrique: Yes. In this, Protestants are much more practical, because they do not confess and do not atone for guilt, they expiate sins by contributing to society. That is why Philanthropy is so common in Protestant countries and not in Portugal. In Portugal, we confess. And the atonement translates into prayer. (Smile)

Was your time in England financially difficult?

Domingos Henrique: No. When I started, I had not yet done the viva voce exam of my Ph.D. here at the UL, but they paid me immediately at post-doctoral level. Can you believe that they didn’t even ask for a certificate as proof of my training? It was a matter of trust, they took my word for it. Of course, there were reference letters and works I had done, but they never asked me for anything else. And even today in Portugal, if we want to have FCT funding, we need to provide all the certificates (even residency ...). Foreign students must register their master degree, or bachelor degree at a Portuguese university, and if they are not European, they must be ratified by a Portuguese university.

Has British society been closing in on the world more recently?

Domingos Henrique: It remains much more open, but the extreme competitiveness part of science and this misconception of what is called meritocracy, ended up affecting the system globally, causing it to turn on itself.

I noticed that you subtly questioned the current concept of meritocracy in Science.

Domingos Henrique: The problem is this: not all of us have an open and direct way to reach such a meritocracy. In science too. It is very important what has already been done, where one has been and the work connections and network of contacts. And the question is how are we going to explain this to those who have dreams, like the people who are starting their doctorates.

It is too crude an approach.

Domingos Henrique: It is one of the biggest problems. But it is important to note that we have data that reflect the high success rate of Ph.Ds. in the PD-CAML. This is due to factors implemented in the past by Professor Ruy Vitorino and that have been continued by Professor João Eurico. For example, the rigorous analysis and evaluation of doctoral projects allows the Scientific Committee of the PD-CAML to often require the reformulation of the initial projects. We think that this process results in increasing the quality of the project and its chances of success in the end. So, prior review work is an advantage.

The thesis committee has also helped a lot in the final rate of success of the theses, because it allows the monitoring of the work and timely intervention in solving scientific problems. I can say that we have practically a 100% success rate in the PD-CAML. Projects that do not come to an end are usually due to other problems, such as burnouts or health problems.

Is this work group also affected by mental health problems?

Domingos Henrique: It is always difficult to deal with mental health issues. We are about to launch a general survey involving all current Ph.D. students at PD-CAML, so that we know the problems related to the mental health of our Ph.D. students. But some results from a more restricted survey carried out recently by the student committee suggest that about 40% of our doctoral students say they have suffered from mental health problems during their doctorate. This numbers surprised me, but the data is similar to what I know globally

How can we deal with the problem?

Domingos Henrique: English style. Having a tutor, or a group of people who can be advisers, help and guide. Then there should be clinical support if necessary, with psychology or psychiatry care. This support is essential to reduce the few dropouts we have. Then we have another scenario that concerns me, which are the few people who, after their Ph.D., want to stay in Science.

And why?

Domingos Henrique: In my view, there are several problems that may be contributing to this fact. On the one hand, the prospects of having an autonomous scientific career seem weak and there is a general feeling that it is a very difficult career, with many obstacles that do not depend only on the scientist. And the financial aspects may also not be stimulating, I admit. But beyond these, another problem concerns me more and is being debated a lot in the international scientific community. It has to do with the image that is being formed of “fake science”, either for reasons of reproducibility of published science, or for matters of intellectual seriousness. I think that doctoral students are very sensitive (and thankfully!) to this issue of intellectual seriousness. For them, science is associated with truth, inherent to the concept of discovery. And if this value is called into question during the Ph.D., the charm of science may fade. Not to be confused with the frustration of “failed” experiences, for technical or even conceptual reasons, or with the “falsification” of hypotheses, a process of destruction of “truths” that is part of learning in science. I think doctoral students learn well to deal with the anxiety of these failures, with the help of their mentors. It is more difficult and destructive to face the lack of scientific seriousness, and I suspect that this may be one of the reasons that can lead to disenchantment with science. An ethical problem, isn't it?

Okay, and what is the price one pays for assuming this ethics?

Domingos Henrique: (Laughs) We started the conversation like this, didn't we? We asked if we would have a price. I think Scientists have theirs too. Corrupting someone's mental tissue costs a lot ... But it happens.

I have realized why they often say that in year 1 (of the total 4 years of the Ph.D.) they start with the romantic vision of Science and end up with some disenchantment.

Domingos Henrique: It is normal to start with a certain naive view of Science. This disenchantment is a process that we are experiencing at a more general level today, with the outbreak of science in the public sphere during this pandemic. Observers less familiar with the scientific process may be surprised by the variety of views and opinions of scientists on the subject. It seems that there are multiple scientific truths about issues that should have only one answer. But this is the normal process, it takes time and a lot of collective effort to reach a conclusion that offers a solid, fact-based explanation of each problem that science addresses. Many scientists place and test hypotheses that later prove to be wrong, but this is normal, this is how we get closer to a convincing explanation. We have to identify well what are hypotheses, what are data and what are facts. This is the problem of communicating science, which implies to distinguish these concepts well and to avoid comparing “apples with oranges”.

There are also several cases when these doctoral students drop out of a scientific career because they feel they are not being useful to society. This concept of "utility" permeates the ambition of many young scientists and can be counterproductive, in my opinion. There is a curious thing that has alerted me to this reflection, when analysing student applications for FCT doctoral grants (and others), in a process that we implemented at the iMM to help them have a competitive application. When reading the letters of motivation, it is almost a norm to affirm that they want to cure some disease, reduce some suffering, or even change something in humanity. But very few letters say they want to discover things, add knowledge with their curiosity as the main motivation.

I think that the greatest value of science is knowledge and what allows us to explain reality. And not all knowledge is of immediate application or social utility. It may seem utopian and disconnected from the current reality, but I think that the production of knowledge must be the primary concern of the scientist, beyond the valid question of "what is this for?". And by the way, it would also be good, in my opinion, for the University to assume that its function is not only to transmit knowledge, but also to produce it.

Did you also become disenchanted with Science?

Domingos Henrique: At this point, I admit that yes, a little. But I think that there is always a process of regeneration, often only underground, and that the value of scientific knowledge will always be present. But science is not separate from the rest of society, and in this era of "fake news", this culture ends up spreading to all areas of society. I believe, however, that scientists can resist this wave, with the daily practice of discussion and doubt, sowing questions and criticizing insufficient answers.

Do doctoral students inspire you?

Domingos Henrique: It is fabulous, there are fabulous minds, bubbling up ideas, wisdom. Learning what not to do is very easy, but learning from smart people how to do it is more difficult, it takes time, but it is the path that I always suggest to young PhD students. I understand that Science alone should be stimulating for everyone, always asking new questions and having new doubts. But this destruction process leaves its marks and it is not easy. This is perhaps the most interesting challenge of the entire Ph.D., learning to sow doubts without burning the fertile ground.

Domingos Henrique belongs to the group of curious minds who look with wisdom at current times, where scientists have become first-rate protagonists. He also looks at a civil society thirsting for cures, giving science a leading role, but only as long as it quickly resolves its problems, otherwise it will no longer be visibly useful. The self-centred that was talking to me and was destroying the routines of time and the rituals of Science.

Starting a new course for the students who started the Ph.D., Domingos has been thinking about how he will motivate them, but also alert them without breaking the spell. He smiles and says he wants to foster the will of those who dream. Those who dream are those who still look at the Laboratory with curiosity and who do not give in to the fear of time, or of understandable sustainability.

Had he not been a runner, he would have found the final words to his new Ph.D. group a mere final expression, which is his life mantra.

“Don't Stop. Keep going”.

Joana Sousa

Editorial Team