On 8 March, International Women's Day was once again celebrated. More than six hundred years ago, women began demonstrations against the submission to which they were subjected for centuries by their male partners and to fight for their rights as human beings inserted in society.

Women have always been the object of difference, often subordinate to men, according to the various cultures and societies, which have frequently been characterized as sexist.

It is believed that in primitive societies, considered matrilineal (descent was defined by the maternal lineage), women were considered to be superior beings because they have gestational capacity, since the sexual act was not known as a factor responsible for reproduction. The tasks were distributed according to physical strength and the responsibility for the children was collective.

When people stopped being hunter-gatherers and discovered agriculture, the domestication of animals and herding, family and social ties changed. At that time, men realized that the birth of the children did not depend only on women, but on the couple. Men endeavoured to gather animals and properties in order to leave an inheritance to their children.

Recent studies and evidence suggest that women had an active role in hunting, transporting animals for food and collaborating in cutting them to pieces.

Over the centuries, the image of the woman was synonymous with servant, while being a man meant being free. The predominant functions of women were reproduction, taking care of the home and educating their children.

The family in ancient Egypt had a patriarchal organization. Depending on her social class, women could participate in religion and politics. In this society, both men and women led the Egyptian people, and the deities of both sexes had the same qualities and powers.

In Greece, where democracy was born, women had no right to citizenship. They took care of the maintenance of the home, of the children and of the weakest, such as the oldest, sick and disabled. They were assigned a place in the residence, the gynaecium, where they stayed with the children and the servants. They could only go to the other rooms of the house to clean and tidy things up. Male children were removed from their mothers from the age of seven for military training in Sparta. Women were prohibited from various activities such as the arts, philosophy or politics.

Also in the Roman Empire, the pater-families was institutionalized. Women, children and slaves were under the absolute power of men. Women had no right to property and could not participate in politics or public life.

In medieval times, women were treated in a submissive way just for the simple fact of their condition of being women, except in the case of widowhood when they had the right to property and the possibility of taking over the family. Their existence was limited to work, suffering, death, control, and punishment.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 B.C.-322 B.C.) said that the submission of women to men resulted from the superiority of male authority over the couple's wishes. The woman had to fulfil the role of mother in the education of children. Dominated by men, women could not achieve their ambitions, nor could they choose their relationship with others.

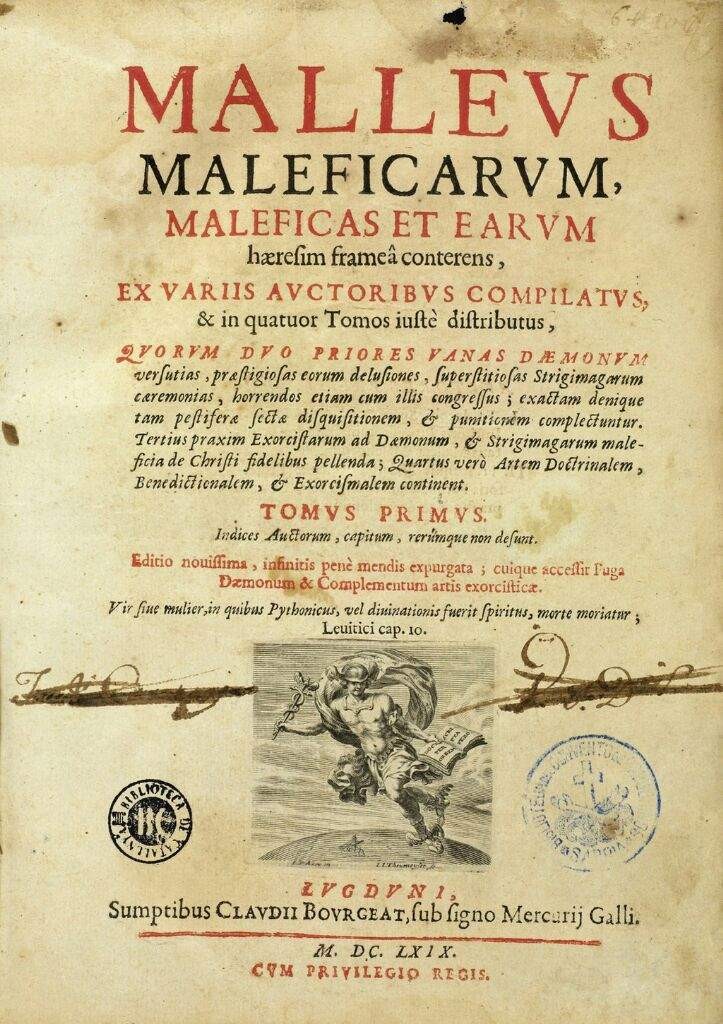

In the Middle Ages, persecutions against women known as “witch hunts” emerged in Europe. Many women revolted against what was “traditional”, and, in turn, societies revolted against them, calling them witches. Many suffered aggression and lost their lives at the stake.

At the end of that period, despite daily interests roaming according to male conveniences, new laws emerged that also referred to the female circle. However, they contained many restrictions on women's rights, both in private and social life. In those laws, the subordination of women to men was evident.

At the end of the Middle Ages, due to growth in the urban economy, a new model in relation to work arose. In this context, women were included in this project, assuming a very important role in the development of cities, reconciling it with the tasks that were previously assigned to them.

Despite the opportunity for women to gain social and professional independence, there were still several barriers imposed in the political, economic and mental fields. The idea that that the training of women was aimed at home economics and the family environment was maintained, with no opportunity to obtain professional or scientific training.

From the 14th to the 16th century, women were not deprived of work, but they worked in very precarious conditions. Those who had some activity (hired for household tasks or with occupations in the clothing industry) as a way of survival, were discredited. Female labour continued to be devalued, which led to the exploitation of female labour, translated into reduced wages compared to those of men.

At the end of the 15th century, the inquisitor Jacques Sprenger published the “Malleus Maleficarum” (The Hammer of Witches) where he made reference to the sacred texts that described the creation of the first woman, who, having been created from a defective rib of Adam, was considered an imperfect living being.

With the Industrial Revolution (in the second half of the 18th century) and the evolution of capitalism, new changes came for women. New possibilities of work arose, but also new forms of oppression and exploitation. Contracts were made by male heads of household. The tasks performed by women were confirmed by men and it was men who received the payment, thus making the work of minors and women in the labour market imperceptible.

However, there are records of several women who throughout history and in several countries, exercised professions in many scientific areas, which until then were considered male.

For example, in ancient Egypt, there was a medical pharaoh named Hatshepsut who planned expeditions to discover new medicinal plants.

Theano, a female Greek student who later married Pythagoras, was the author of books on Mathematics and Physics.

Hypatia, too, lived around 370 A.D. She invented the densimeter and became known as the first mathematician in history. She studied mathematics, astronomy and taught mathematics and philosophy in Alexandria.

In Greece, Plato allowed his classes to be attended by female students, but they had to dress in men's clothes. In many Greek cities, there were female doctors and surgeons, however in Athens, many women were accused of performing abortions. Therefore, a law was issued that forbade them to practice medicine and gynaecology.

Eric Sartori wrote in his book L'Histoire des grands scientifiques français, that in 300 BC, Agnodice, descendant of a noble Greek family, dressed as a man to study in Alexandria. Back in Greece, she practiced medicine, denouncing her identity only to her patients. This doctor became very popular, which upset her colleagues. She was sentenced to death, but was saved on the day of the trial thanks to the imposition of hundreds of Athenian women.

In the Middle Ages, monasteries were institutions dedicated to education. They accepted women and stood out in the history of scientists. This was the case of the German-born abbess Hildegarde Von Bingen who, between 1151 and 1158, described three hundred plants, minerals and metals with therapeutic properties, giving rise to a pharmaceutical encyclopaedia.

In Salerno, Italy, at that time, there was a medical centre that stood out for hosting both masters and female students. The most famous was Trotula, a gynaecologist and obstetrician who wrote two medical treatises on women's health.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, despite the enormous expansion of universities across Europe, which contributed to an enormous wealth both socially and culturally, as French historian Eliane Viennot wrote in her article Les intellectuelles de la Renaissance, the transmission of these values was still restricted to men, alienating women. Nowadays, some specialists learned through works written by Aristotle that indicated that the feminine gender was inferior to the masculine gender, a system that remained until the 19th century.

It is known that at the beginning of the 18th century, female elements of noble Swedish and English origin studied and produced knowledge, such as Elisabeth of Bohemia and Queen Cristina of Sweden.

In mid-1700, in Germany, Marie Winkelmann Kirch discovered a comet and wrote important treatises while working alongside her husband. After his death, the Berlin Academy refused her the position of astronomer. Years later, the same position was offered to her son, giving Marie Kirch the opportunity to become his assistant.

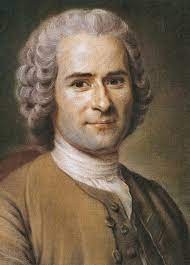

In France, women from the upper classes attended private courses and met in salons where they debated literary, philosophical and scientific issues. These meetings ended with the arrival of the French Revolution and with the ideals of Rousseau, who affirmed female inferiority and submission.

In his work Emile or Treatise on Education published in 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote “I would prefer a simple and uneducated girl a hundred times over a woman with intellectual and literary pretensions who would turn my home into a court of literature over which she would preside. A bluestocking is the scourge of her husband, of her children, of her servants, of everyone. From the sublime elevation of her genius, she disdains all her womanly duties”.

Charles Darwin (1809-1882), a British naturalist, geologist and biologist, admitted that “In order for a woman to reach the same level as a man, she should, when almost an adult, be trained for energy and perseverance, and have her reason and imagination exercised to the fullest”. In his work The Origin of Man, he suggested "that women would need an extra effort to reach the intellectual capacity supposedly inherent in men".

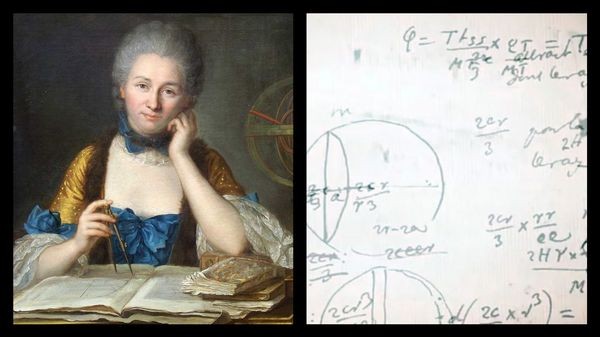

At the beginning of the 19th century, there were countless women who, despite remaining self-taught and taking private lessons, contributed a lot to scientific production and development. It was the case of Émilie du Chatelet, Voltaire’s collaborator and Newton's translator into the French language, who published numerous works that contributed to the development of theoretical physics.

Of French origin, Sophie Germain taught herself Mathematics and used a male name in order to correspond with other mathematicians. She received an award from the Institut de France. One of the great mathematicians of her time, Carl Friedrich Gauss, recommended her for an honorary doctorate from the University of Gottingen, but Sophie Germain passed away before that honour was bestowed on her.

Marie-Anne Paulze, who married Lavoisier, translated several works by English chemists and wrote several critiques that provided many advances in chemistry.

Marie Curie, of Polish origin, known as the “mother of modern physics”, was one of the few scientists who were recognized while still alive. She became the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded in 1903. In 1911 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, becoming the first person to win the prize twice.

In the 20th century, some of the discoveries made by men were recognized and overlapped with those of women, such as the case of Lise Meitner, born in Austria and known as the German Marie Curie. She studied radioactivity, collaborated in the discovery of nuclear fission, a term that she published together with Otto Hahn, her nephew and collaborator, in the journal Nature in 1939. However, only Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944.

Juana Miguela, an Argentine specialist in Entomology, described 11 species of mosquitoes hitherto unknown. Despite being recommended by her professor, she was refused the position of professor of Zoology at the Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences of the University of Córdoba, in 1920.

Isabel Ramirez from Mexico and Zélia Nutal, from the US and who lived in Mexico in the early 20th century, were marginalized by the scientific community and it was only in the 2000s that their research was recognized.

Still, there were women whose discoveries were recognized, like Florence Rena Sabin, an American scientist and doctor who studied the lymphatic and immune systems of the human body. She was the first woman to earn the title of "first lady of American science" and a seat at the US National Academy of Sciences in 1925.

Medical doctor Virginia Apgar, an anaesthesia specialist, discovered that some substances that were used as anaesthetics during childbirth harmed babies. She created the Apgar Scale, which was developed in the 1950s, an exam that evaluates new-borns in their first moments of life.

Biochemist Gertrude Belle Elion, who was born in Canada, created drugs to alleviate the symptoms of leukaemia, herpes and HIV AIDS. In 1988, she received the Nobel Prize for Medicine.

Until the nineteenth century, there was great intellectual development of men, while women remained stagnant. There are no records of women attending university. The profession of midwife, an activity that had been attributed to women, was replaced by obstetrics, a specialty exclusively for men.

This attitude and the inferiority to which women were subjected led them to begin to challenge gender inequality mainly in access to work and education, seeking to obtain the same freedom and the same opportunities that men enjoyed.

In 1404, French writer Christine de Pizan (1364-1430), considered one of the first feminists, published “The book of the city of ladies” where she advocated equal education for both sexes.

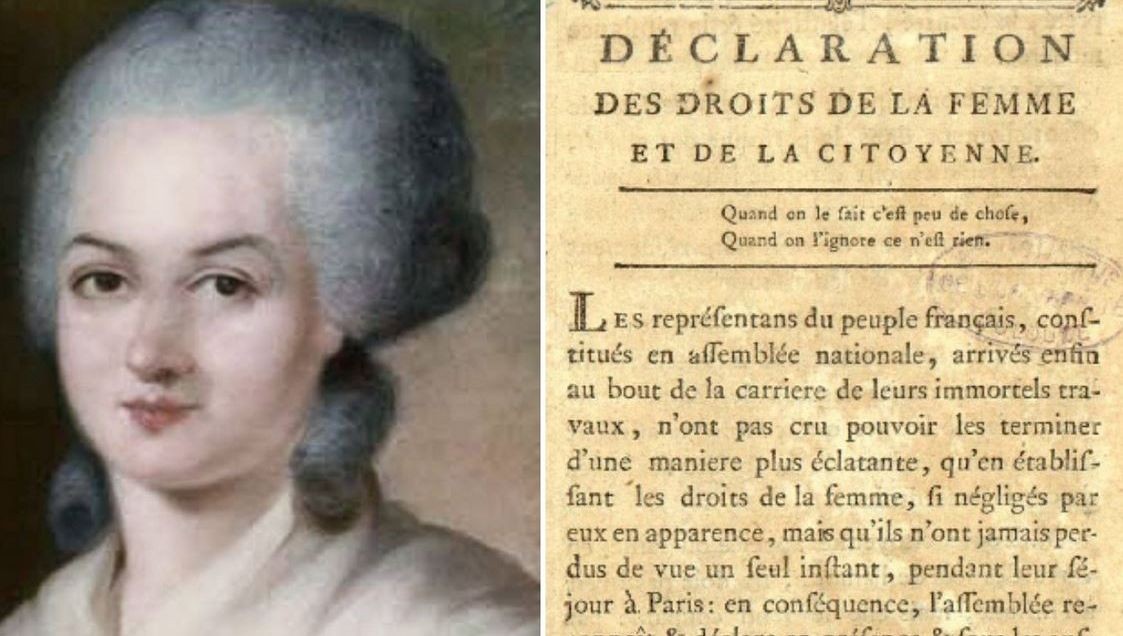

At the time of the French Revolution, several women fought and demonstrated against these situations. Olympe de Gouges, of French origin, disgusted with the submission of women in macho societies, presented the “Declaration of the Rights of Women” with the intention of ending the privileges that were exclusive to men. Accused of having abandoned the “benefits of her kind and trying to be a statesman, she was sentenced to death and died in the guillotine in 1739.

From the 18th century onwards, with the Enlightenment, there was a movement marked by increased appreciation of female intellectuality. By this time, Mary Montagu and the Marquess of Condorcet, two educators with texts and ideas for the defence of women's right to education, stood out.

In 1785, in Middelburg (Netherlands), the first Scientific Society for Women was founded. Universities began to allow women to enrol in some degrees, except medicine and law.

French women were not submissive and continued to fight, achieving several victories such as the right to vote. At this time, the feminism movement gained momentum and started to be considered as a political and organized action. It wanted to claim the rights of women in the face of the obstacles they faced, and it became involved in the struggle of women.

In England, feminism was marked by the criticisms that writer Mary Wollstonecraft made about Jean-Jacques Rousseau's thoughts. The latter stated that there were two worlds, the external world where men belonged, while women belonged to the internal world and that was why they should always be at the service of men. Mary Wollstonecraft criticized the differences between men and women in terms of intelligence and character. As the education given to female elements was considered inferior, she suggested that women should have the same opportunities for intellectual and physical education men.

The same was true in the USA. When people commented on equality between men, they only referred to male elements and excluded not only women, but also Indians, people of colour and low-income men.

In Portugal, the first activist attitudes, the overthrow of prejudices and the attempt to achieve new conquests in the female milieu were carried out by Carolina Beatriz Ângelo.

Carolina Beatriz Ângelo was born in Guarda in 1878 and died in Lisbon in 1911. At the age of 25, she completed the medical degree at the Medical-Surgical School of Lisbon. A courageous woman, she was an activist and suffragette. She was the first woman to practice surgery at S. José Hospital.

In 1907, she joined the Portuguese Group of Feminist Studies, which opposed the participation of the Church in public life and defended the divorce law. That same year, she created with Ana Castro Osório, Adelaide Cabete and Maria Veleda, the Republican League of Portuguese Women. In 1908, she led the Portuguese Feminist Movement that defended the struggle for gender equality.

She was the first Portuguese woman to exercise the right to vote. After the 5 October Revolution, the electoral code attributed certain conditions for the right to vote: "all Portuguese over 21 years old, on the date of 1 May 1911", "residing in the national territory, who knew how to "read and write” and were “heads of household”. Carolina Beatriz Ângelo believed she met all these conditions, as she had a university degree and, as a widow, she was the head of the household. After asking to be included on the electoral roll, her request was rejected by both the Census Committee and the Ministry of the Interior. However, a judicial decision (directed by Ana Castro Osório's father) was favourable to her.

As she was the first Portuguese woman to vote in the elections for the National Constituent Assembly, this event was reported in the entire European press.

The idea of founding a National Women's Council ariso in our country only in the early years of the twentieth century. It was when Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcelos introduced Sophia Sanford, treasurer of the International Council of Women (the oldest American international feminist organization, founded in 1888) to writer Olga de Morais Sarmento. However, it was only in 1914 that the National Council of Portuguese Women was founded, as one of the branches of the American organization (which already had other Councils worldwide). Adelaide Cabete (1867-1935), physician and activist, was appointed president, a position she held until 1935 and Carolina Michaëlis was invited as honorary president.

The National Council of Portuguese Women was the most enduring Portuguese feminist organization in the 20th century, from 1914 to 1947, when the Salazar’s Regime ordered its closure. This organization struggled for “just and human equality” and played a extraordinary role in the struggle for the emancipation of women. This occurred since the beginning of its foundation, at a time when the activists complained about the critical and anti-feminist speeches they witnessed, and about the time spent explaining what feminism was rather than announcing what they really stood for.

At a time when, for a woman to be able to travel, she had to have authorization from her husband, Adelaide Cabete, a widow, with diplomatic passport, participated in several congresses representing the Portuguese government, such as the Congress of the International Council of Women that took place in Washington in 1925.

Her participation at the congresses and the various topics discussed, the bonds of friendship and the contacts created with activists from similar institutions in other countries (National Council of French Women, Brazilian Federation for Female Progress or the National Council of Women in Uruguay) influenced Adelaide Cabete to act in “the struggle for the political, civic, economic, educational, and labour rights of women in Portugal”.

The National Council of Portuguese Women, as well as other women's associations in Portugal, were essentially made up of female members who practiced recognized professions, as doctors, nurses, lawyers, teachers, pharmacists, writers, artists, and also housewives.

Influenced by the International Women's Council, the Portuguese organization led by Adelaide Cabete organized several Portuguese charity, humanitarian and defence of professional rights associations.

Over the next 30 years, 24 associations were created and supported various sectors: childbirth assistance, maternity support, professional training for disadvantaged girls, granting of scholarships, loaning books to poor students, allocation of clothing and footwear, and fight against alcoholism, among others.

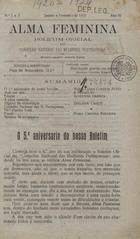

In 1924, the National Council of Portuguese Women (CNMP) held the Feminist and Education Congress. This meeting was widely reported in the press, arousing the revolt of Portuguese women regarding the living conditions they had. The publication Alma Feminina – Female Soul (CNMP's propaganda publication that started with the title Boletim Oficial - Official Bulletin and ended its publication as A Mulher - Woman) described the feminist position of the then President of the Republic, Manuel Teixeira Gomes, when he was present at that meeting and expressed his surprise that women in Portugal did not yet have the right to vote.

During the 1920s, the CNMP had extensive activity in the fight against inequalities of rights and the right to equal pay for men and women, civil rights for women in marriage, special conditions for pregnant and breastfeeding women, literacy and professional training for girls, and the difficulties imposed on them by the government of the First Republic led by Sidónio Pais, the Military dictatorship and later by the Salazar’s Regime.

With this new system of government in Portugal, which opposed feminist ideals, above all because of its struggles for democracy, and concerned with the direction that the CNMP could take after Maria Lamas (1893-1983) became its president, it was decided to close the National Council of Portuguese Women in 1947.

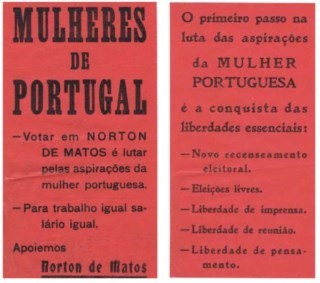

In the years that followed, many women formed various movements (against the authoritarianism of the Salazar’s Regime) incorporated in the candidacy campaigns in opposition to the elections. The interventions intended to overthrow the regime and institute parliamentary democracy.

Among the many movements that have been organized, we can refer to the Women's Committee of the Democratic Unity Movement (MUD) in 1945, the Women's Democratic National Movement of the National Democratic Movement that operated between 1949-1957, the Women's Electoral Commission for the Candidacy of Humberto Delgado in 1958 or the Female Nucleus of the Electoral Commission for Democratic Unity-CEUD in 1969.

In these groups (some were created as others were extinct), there were women (like Maria Isabel Aboim Inglez in the Movement for Democratic Unity in 1945 and Maria Lamas and Virgínia Moura in the National Democratic Movement in 1949) who stood out by alerting about the obstacles and situations of gender inequality that they faced daily in the family environment, at work, in social assistance or in political participation. Their demands covered both the economic, social and moral spheres of women, who had the duty to encourage and collaborate with their male peers whatever their religious, political or social beliefs.

Fig.28 - Maria Isabel Aboim Inglez

Fig.29 - Virgínia Moura

Although there have been acts of inequality and discrimination against women, there has also been evidence of their participation in the political sector that has contributed to the realization of their ambitions, in a more gender-equitable way. The presence of women's electoral commissions in the opposition lists of the CDE (1969) and CEUD (1969) were the impetus for the solid revolutionary presence of women in the Constituent Assembly after the April Revolution in 1975.

With the fall of the Estado Novo in April 1974, women became emancipated, won the right to vote and new horizons were opened in professional terms. They occupied places that were exclusive for men and many of the barriers were removed. However, today, more than forty years later, there are still many examples of gender inequalities.

References:

- Abrahão, Regina. O papel das mulheres através dos tempos. Available at https://ctb.org.br/sem-categoria/o-papel-das-mulheres-atravdos-tempos/ [Retrieved on 12-03-2021]

- Uma análise da história da mulher na sociedade. Available at https://direitofamiliar.com.br/uma-analise-da-historia-da-mulher-na-sociedade/ [Retrieved on 12-03-2021]

- Beatriz Ângelo, a primeira mulher a votar em Portugal. Available at https://ensina.rtp.pt/artigo/beatriz-angelo-a-primeira-mulher-a-votar-em-portugal/ [Retrieved on 12-03-2021]

- Cem anos de lutas femininas e feministas em Portugal: o exemplo das pioneiras. Available at

- https://www.publico.pt/2020/09/27/sociedade/noticia/cem-anos-lutas-femininas-feministas-portugal-exemplo-pioneiras-1932367 [Retrieved on 12-03-2021]

- Correia, Rosa de Lurdes Matias Pires. O Conselho Nacional das Mulheres Portuguesas: A Principal Associação de Mulheres da Primeira Metade do Século XX (1914-1947). Available at https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/12614/1/ocia%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20de%20Mulheres%20da%20Primeira%20Metade%20do%20S%C3%A9culo%20XX%20%201914-1947%20Rosa%20de%20Lurdes%20Matias%20Pires%20Correi.pdf [Retrieved on 12-03-2021]

- Cem anos de lutas femininas e feministas em Portugal: o exemplo das pioneiras

- Karoline, Ana. O papel da mulher na sociedade. Available at https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/geografia/a-importancia-da-mulher-na-sociedade.htm Retrieved on 12-03-2021]

Lurdes Barata

Library and Information Area

Editorial Team