- A Talk with Catarina Jacinto Correia“

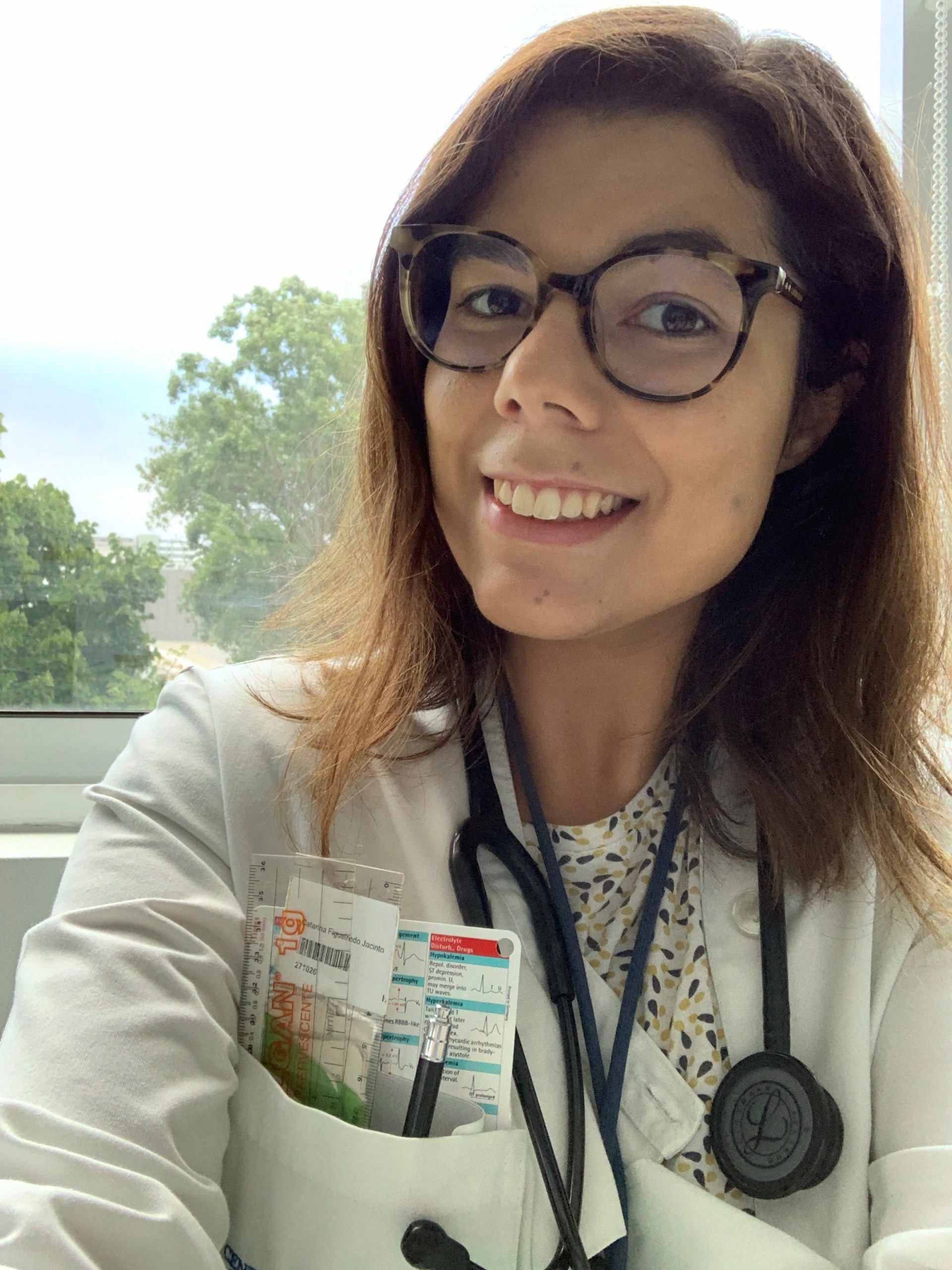

She has just arrived from the COVID19+ infirmary, saying "sorry my look" and she even apologised for her understandable tiredness.

Since the first wave of this pandemic, she volunteered to help in the “COVID emergency room”. Initially she combined her area with that of the ER. Now she deals with SARS-CoV-2 day and night, facing it with a smile that in these times of greatest tiredness seems rare. "We should all help at this stage, those who have the time for that", explaining the reason for volunteering for the ER. She is concerned about those who are on the ground from the beginning and without a network to be able to give up, or have a break.

As an internal immunohemotherapy doctor, she explains that an average of 40 hours a week is always expected, plus extra consultations during that time, something that usually represents an average of 46 to 50 hours a week. Reasonable, I think, after all it is tiring, but it is possible to manage. It would be if like that if this was the case, but it is not.

Since the first wave, she added another extra night to her agenda. She integrates the "COVID ER", ensuring 12 nonstop hours. This is in addition to her usual work, but if necessary, she I would work a few more hours, if that would help to see the many patients waiting to be seen. The avalanche of the pandemic meant it would be necessary to equip the teams with more people. Some external doctors joined in, but the biggest mobilization was that of Santa Maria interns who joined the “COVID areas” in vast numbers. The setting became a military situation, in terms of the endurance, number of hours and effort. Starting work at 8 am and leaving at 8 pm or sometimes later - 10 pm, 12 pm... In addition to the 10-12 hours of daily work, Catarina also works in the Medicine 1 wards (sometimes working 18-24 hours nonstop) and external ERs, as she has done since the beginning, in the "COVID ER".

One may well think that one loses track of the number of hours and of tiredness. It is true. They sometimes work for 24 hours without stopping. The long hours mean experience, but also tiredness, not mitigated by the 5-6 hours that she sometimes has to go to bed before returning to the hospital.

Catarina Jacinto Correia would finish the immunohemotherapy internship at the end of 2022. Currently in year 4 of the specialization, and already with 5 years of medical practice, she would only be missing a year of internship. However, her transition to a specialty was interrupted due to the mobilization to the areas of Covid Medicine. Accordingly, she knows that her home will most certainly be Santa Maria Hospital, at least until 2023.

If the pandemic does not worsen, Catarina will maintain this rhythm and offer full-time support to these wards until the end of March.

Defeated by the idea of not finishing the internship in the near future? I try to probe, but she smiles, as she did during the whole conversation. In her, calmness reigns above all frustration. It all makes sense if we listen to her for a while. Helping people is something she has wanted to do since she was 5 years of age, when she decided to become a doctor.

At the age of 5, however, she was not told the stories that reached Santa Maria Hospital last month. It was the extreme care for others that kept her away from her loved ones. It is strange, how life contradicts itself as time progresses, as in a book of her old stories. In the first wave, she didn't go home, she protected her family in such a way that her mission was not to put anyone at risk. She only revisited them in the summer, when the pandemic seemed to calm down. Without Christmas, or unable to be with friends and family, Catarina, who just turned 29 on the 9th of the month, had to celebrate her emotions from a distance, using new technologies, as if her presence was now her worst shadow.

With a critical stance inherent to her mission, another feeling clouded her thinking. Learning was a must! In the 1st stage, she volunteered to work at the “COVID ER”, but without ever forgetting that it was necessary to gain new knowledge. She studied a lot, read much in order to iron out the curves of the path that she chose for herself. She studied online, researched scientific articles, and took a course in non-invasive ventilation and another one on how to deal with critically ill patients.

As every cloud has a silver lining, Catarina Correia realizes that perhaps now people see the National Health Service with more affection, as its image had been so worn, week and forgotten for so long. She did not leave the boat in the face of a storm. Investing and providing conditions to the NHS and the University hospital where she works is what she wants, almost as if it were a Christmas secret, for the good of the Faculty where she studied.

Let us take a look at her path.

Helping people has marked her soul. It is the only justification she finds for someone who has no connection to Health. Perhaps Law or Management Studies, closest to her. Perhaps she would follow a professional path identical to that of her family. But this inherited past was of no use, not in terms of first choice, because later on she did postgraduate courses in Medical Law and in Health Management and Leadership.

The Medical Degree at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, was her first option. And that's where she stayed. The choice of the Faculty was not a matter of chance, the connection to Science through the iMM and the contact with Pedagogy, as well as with scientific studies, were choices she made from an early stage. “The difficulty with Medicine is not to enter it, but to stay”, she explained.

Staying is a fundamental aspect for those who learn the notion of resilience, so very much trained in the last few months.

When she completed her medical degree, she decided to carry out the common year at the Central Hospitals, between Curry Cabral Hospital and São José’s ER. By comparing hospitals and services, she gained different experiences.

The specialty arose out of her predilection for decoding coagulation and haematology. She says that the fact that she had family with haemato-oncological disease explains why she did not choose haemato-oncology and opted for another area related to blood. Haematology yes, but the benign one, and that is why she chose coagulation, anemias and hemoglobinopathies. Her eyes shine, vibrant as a child in the presence of various sweets. "I really like seeing patients, but I also really like the laboratory and being able to 'pipette'”.

Whereas she hesitated about Internal Medicine, which she loves, after pondering, she realized that Immunohemotherapy would allow her to trod other parallel paths, take more courses and training and allow for a new master degree and maybe a Ph.D. She has also took a course at the Catholic University in Management for Young Doctors and hopes that the experience will allow her to take a second round - Health Management.

When Catarina Jacinto Correia's routine returns to "normal", she will continue to see her patients in person, in an outpatient and day hospital, and to support the laboratory and manage the stock of blood and blood products. And as she never stops more than a few minutes, she is currently studying a Master degree in the area of anti-thrombotic treatment, at the University of Murcia, after completing a Health Innovation programme at Harvard Medical School and the MIT. This is one of the advantages of the pandemic allowed, bringing the world together in one space, the virtual one.

Her curiosity did not stop here. During the common year, she took a course in Emergency Medicine and Catastrophe. She had planned to go to Africa to apply the knowledge of that Medicine, but now she trains it daily, for many countless hours in her own country.

Naturally empathetic, she speaks of "her patients" with a heightened sense of responsibility towards others, more now when she hospitalizes them. She is genuinely happy, despite saying that "she is not as happy as she used to be", because when she gets home she is still thinking about who she left at the hospital. She laughs with her eyes, and tells me that dozens of questions go through her mind, "is that man decompensating?", "Will she find the same people she left in the infirmary?".

More than once she praises her peers, the Internal Medicine doctors who inspire her. Even in the face of extreme tiredness, they continue to follow the same difficult path and are willing to continue.

I met Catarina when I read her request for help. I thought then that the best way to help her was to give her more space to report objectively what our eyes do not know and, as such, some people think it is all an exaggerated construction.

“Today I started to provide 100% support in the COVID19 ward, which receives unstable patients undergoing non-invasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy, in addition to the emergency work at the COVID ER that I have been doing since March. I stopped almost entirely the activity in my specialty, in my service, in order to come and help colleagues who are completely exhausted and are doing their best every day. They need help, here and in all hospitals all over the country.

As you can see, the situation is not improving and there are many who need medical help on a daily basis and who resort to health services. At this rate, it will not be possible to provide care to all.

Please follow the instructions, be Public Health agents; help us to be able to help!

Thank you ”- Catarina Jacinto Correia

I think that at this moment we all imagine of what it will be like to be in an emergency in Covid. But can you tell me what happens?

Catarina Correia: It is important to understand the evolution of Covid emergencies, because they have been built in our hospital over time. During the various phases, there have been several Covid wards. Initially I started to give support in the tents - which had much more fragile conditions, it was very cold, because the structure itself did not isolate well, and we still did not have much support, either in terms of knowledge of the disease, nor in human terms or materials. It looked like we were practicing war medicine. But it was the possible answer, in the short reaction time. Then it evolved. We even had a phase when we went to the 1st floor of the hospital, an impressive structure that I was proud to see built in record time. Now there are phased screenings, a structure completely separate from the normal ER circuit, better conditions and more structuring and organization. But if conditions were more precarious at first, it was also easier to see all the sick. This is not the case now, and since the beginning of this year things have become more complicated regarding the number of people arriving. I don't remember my worst emergency, either in Santa Maria or São José, where I saw so much affluence. In a single day this year, we had around 50 ambulances waiting to bring patients in, in addition to the countless ones we had already waiting in the screening area and even in the COVID ward and treatment rooms ... there was nowhere to put them. That was scary, because we had the whole structure set up, we had teams and support from people from different areas, but there was no more space. The COVID area, a container outside the hospital where suspected Covid patients are, already had a considerable number of beds and observation areas, and even so we had to start seeing and starting therapy to several people in the screening area.

Whereas I thought that the tents in March 2020 were war medicine, almost a year later I realized that a catastrophe can always get worse, and even though the physical conditions are better and scientific knowledge is greater, the context makes all the difference. At this stage, yes, we entered a real war scenario. So, as we were unable to move people between areas, because everything was packed, people started to wait in the COVID ward itself. There was no longer any space for internment. That explains why so many ambulances were waiting. Only very exceptional cases, such as Reanimation or emergent situations could have direct access to the hospital. All the ER Team Directors went to the ambulances to see which cases could wait in there, and which had to be seen immediately. But it was very hard. This phase was very complicated, we felt completely powerless.

This scenario of absolute chaos took place in January only, right?

Catarina Correia: Yes, January was undoubtedly the worst time. Of course, since March of last year, we have had peaks when things got worse, but never like this. In January, what happened to us was not normal, the general ER itself had to be changed at the most difficult time of this wave to accommodate more areas for Covid+ patients. There was a particularly bad night when even the "orange" areas of the emergency room had Covid patients, the "green" area also had to open for these patients, and even the "aerosol" room - this was when we received patients transferred from Fernando da Fonseca Hospital, during the complicated situation they had in terms of oxygen therapy capacity. All of this is all in addition to the COVID external area, which meanwhile has been expanded to accommodate almost twice as many patients. In other words, we had a huge number of Covid zones, transforming the non-Covid space into a single space, which was the “yellow” zone. Even with this intervention, there were many people waiting. The nights didn’t slow down, didn’t stop. The teams were exhausted, and however much effort was made, it seemed that we could not reduce the waiting list, reach everyone. We arrived at 8 am (after a 12-hour night shift), when everything generally calms down “in normal times” (without COVID), and we went outside to see 10 or 12 ambulances waiting, even after one night of intense work. And it is hard, very hard - especially psychologically.

What did you feel then?

Catarina Correia: I felt several things. The first of all was to think of everyone who has been working in these areas every day since the beginning of the pandemic. These people are my colleagues in Internal Medicine and Intensive Care. They are also the diagnosis and therapeutic technicians, doctors, nurses, assistants, from all the services that have been affected, even those that sometimes we forget and are more “in the background”. But they are essential; in admissions, in emergency rooms, in the laboratory and areas of test samples, in health centres and in public health management. I thought those teams must be completely exhausted and burnt out. If I spent one night a week in a COVID emergency, in addition to my usual medical work schedule, and felt tired, imagine how someone who, for months on end always worked these hours, always had more hours, without holidays, breaks, unable to telework. When I became aware of this reality, I could only help, help more with what I could. I was called, like other internal colleagues and specialists, but I was already very motivated to do so, as I felt that I could offer an extra contribution and help to reduce the impact and exhaustion of the most affected teams. And so it was. Several of us were called, each from a different area, from the most diverse specialties and medical areas. Some are interns at the beginning of their specialty, others are at the end, others are already specialists. And I, as I already worked in the ER, was called to do full-time admissions in addition to that. This means that my internship is currently paused; I'm in the Internal Medicine department looking after Covid patients. And I am, of course, working much more than the usual hours at my internship. (smile)

Were you prepared to handle this pace of work?

Catarina Correia: I don't think one is ever 100% prepared, because there is always an occasion when we feel tired. But I have the advantage of being young, I am able not to sleep much and remain relatively functional. But I think that for those who are older or have some health issues, or even those who have been at this pace for a long time, without breaks (even when they are young), these schedules are very difficult to manage. The truth is that I have days when I feel very, very tired. Then there are other days when motivation pushes me to help, even if I’m exhausted, and that gives me strength. Another factor that helps a lot is having a team like the one where I work. It is a fantastic team, people are very committed, friendly. They all welcomed me very much and I think they were happy to see new help arrive. Finally, it helps to have a boyfriend who is also a doctor and who is also in the Internal Medicine ward. As such, we know the schedules we both have and as they are anything but normal, it allows for understanding and respect from both sides. It is not easy to manage life at home, but we can take it.

Given such a historic moment, does it weigh more to experience it, or are you worried that not all the professional goals are met in the timing that you planned ?

Catarina Correia: Undoubtedly, it is always more important to care for the sick. Of course, at this stage, it means delaying my professional and even personal plans, but it is for the sake of helping those in need. If I were a mother and had other responsibilities, delaying a year, or a year and a half, maybe it would have more serious consequences. However, that is not my case. I'm 29 years old, I think I'm still young. (Laughs). Now people need me here and it makes me feel like I am not wasting time. I chose this, and what better phase than this to help people? If I do not help now, when we are facing this catastrophe, when will I help? This is the time. It doesn't make me confused if my goals are postponed. What bothers me the most is that we are unable to respond to all patients - those who have and those who do not have Covid. I don't say I don't think about it, because I think about the future - but life is also about knowing how to deal with the unforeseen and with what we can't control.

In relation to non-Covid patients, I have this concern, as we all have. In my specialty, consultations have not been cancelled, our Day Hospital continues to operate at 100%, and it is also important to praise the colleagues who have made a great effort to keep everything going, even with several people away from their services in order to support the Covid activity. Those who stay also deserve praise for “holding the fort”. It is a great help and essential to continue caring for all the people who need it. And even though I am working full time with Covid patients, I continue to follow-up my outpatients by giving consultations, even if by telephone, or between Covid activity. Fortunately, I also have colleagues who have been incredible and who help me and monitor my patients, and whom I have to thank.

But the priorities have changed, because the NHS cannot respond to everything. There are many physical and human resource deficiencies. You just can't do it. And this is what I would like people to think about. We all have to paddle to the same side so that we all have the best possible care.

You were saying earlier that people who arrive at the hospital are in a more advanced stage of the disease, more than usual. And we are talking only about Covid patients. Who are these patients who arrive now that did not arrive so sick in the beginning?

Catarina Correia: There is a very big difference between patients today and those at the beginning. At the beginning of the pandemic, they came much earlier, at an early stage of the disease - at least that was the perception I had in the emergency room. Many people had a headache and were coming soon for a test. There was more fear of being infected. It is not so now. We now essentially receive much more serious patients. Of course, we received a lot of support from the Health Centres and from the Saúde 24 line itself, which has helped a lot to manage patients with milder symptoms, and select the most serious ones for hospital observation. Of course this influences our perception, but it is not only that. People, even with symptoms, have delayed seeking help. They come much later and have endured more until they get here. And then what happens is that when they arrive, the disease is already in a critical phase and tends to get worse. Many patients come to us when they already knew they had the disease, but were under surveillance. Then they got worse and felt the need to come. But we note that the pattern of cases we have most are patients already with severe hypoxemia (very low levels of oxygen in the blood), some needing non-invasive ventilation, and others even going straight to Intensive Care to be intubated. Even younger, less sick people.

Patients arrive with such a high degree of illness?

Catarina Correia: Yes. We even had to do resuscitation in the COVID ward (which, fortunately in our hospital, has its own room for that effect with all conditions). This is because the extent of the disease is already so high, or because the comorbidities are so many, which means that we really need to intervene invasively on an emerging basis. In the Medical ward where I am, we have more serious patients - it is an Intermediate Care ward, and almost everyone is having non-invasive ventilation or high flow oxygen therapy, or they are more unstable patients with the potential for aggravation or need for support techniques such as dialysis, for example. They are often people who then need to go to IC, because there they need to be intubated for invasive mechanical ventilation, or to be subjected to other procedures and monitoring. And in the heaviest phase, we even had days with several patients decompensating simultaneously and in need of orotracheal intubation; young patients. These are heavy situations that demand a lot from the team. In this aspect, the ward where I am also gives me a heavier view of the situation, because they are seriously ill people who need a lot of care.

One of the images that impressed me the most was to see a fireman sitting next to the ambulance at the door of Santa Maria Hospital’s ER. It was dawn and he was looking out into the void. The thought that often occurs to me is, what will the teams feel after a day/night of chaos? Is it just a void without any noise? What goes on in your head at the worst times?

Catarina Correia: It is very difficult... In the beginning it was really complicated to manage my emotions, because I was not working in my specialty, a specialty usually with more stable patients, in the context of consultation, which does not imply this confrontation with Intermediate Care daily. It is hard to see the vulnerability of people who were convinced that they were going to die, even when the scenario did not even point to something so serious. Seeing their despair - the fear of being there, of being infected, away from the family, and of seeing others around them in a serious condition. Seeing people's despair is terrible. The truth is that they see others dying around them, people arrive from places with outbreaks and with the notion of losing family members, or acquaintances. All these situations weaken the sick. There are other constraints on our part that are hard, such as talking to families who are waiting for news of those who are ill. When a patient is very ill with a poor prognosis, we always try that there is a "farewell" from a family member, someone close. Even with all the care in terms of public health, we try to let family members say goodbye to those they love. In my experience at hospital, one always tries not to lose that human side. When it is not possible in person, we try to make phone or video calls between patients and families. And we try to give news every day, whether good or bad, to those who have a family member with us. But it is very hard to see this. It is hard to realise that we are going to lose a patient after everything we did to save him. These moments give us a great emptiness... You know that the patients are a little "ours", because we spend together many hours. At least personally, I feel these things very much. Then, there are days when the lack of sleep and tiredness makes us feel empty, or like crying. There are other days when one feels angry, especially when we see the news and realize that the general public is not being careful, that there is no compliance with safety standards or that people continue to think that this situation is not real, that it is a conspiracy theory. It makes me angry, frustrated, irritated, but also sad.... Only those who do not see what is happening in our hospitals, may feel that this is not happening. This pandemic can touch and reach any one of us, it does not choose the profile of who it is going to attack and sometimes it seems to me that people have not yet understood this. Then I worry a lot about my family.

The family... Interesting the care that all have shown with their families and not with themselves

Catarina Correia: We really want that nothing happens to them, and the distance makes them miss us immensely. I used to have lunch at my parents’ home every week, and I stopped doing it and I miss them. I need their love and affection. I am far away from my grandmother who is in a home in Alentejo and I cannot go to see her - I have not seen her in over a year. Of course, there are calls, but they never replace personal contact. My own grandmother had Covid, fortunately with mild symptoms, and I couldn't even see or help her. My grandfather is in Lisbon, living alone at home. Since this pandemic started, I notice its major impact on him, both physically and psychologically; like him, the most fragile or the most isolated feel the impact the most. All this has implications at mental level, and the elderly “age a lot and faster” because of isolation. Fear causes many things in people... Then there is also the opposite, our family members (health professionals) also suffer a lot; I always think of my mother who also suffers a lot because she is afraid that I will get sick and she worries about the number of hours I work, my tiredness...

Are you afraid?

Catarina Correia: I am not afraid, in the sense that we protect ourselves, we use all protection properly. I try to rationalize. Of course, there is always fear of getting infected, but it is not a paralyzing fear even if it was something that interfered with the desire to continue to be a doctor and help. In the meantime, I have already been vaccinated, had the second dose, which also gives me some hope; but I did not fail to protect myself. And that is a message that has to be passed on to everyone - we must maintain the measures even with a vaccine. We have to create group immunity, but carefully and calmly and always taking into account what we have learned from the beginning, without neglecting care. Now, I'm not afraid. Or rather, above fear is a great desire to help people who are fragile. Being afraid doesn't do any good. And if I have any, it is due to the fear of infecting my family, those closest to me, or those I care for.

You have interrupted your internship to treat patients in an area that is not your own. How is this transition from areas of medicine? Were you ready for this?

Catarina Correia: We are never 100% prepared. What gave me some advantage was that I never left the general ER, even though it was not part of my specialty, for pleasure. And because of that, I never lost contact with Internal Medicine. So, when I started to work in the Covid ER, what I had to learn was the same as for any other doctor in the ER - it was a new disease, in that aspect we were all in the same boat - although those who have more experience or basic training in a specialty that deals more with this type of patients and pathologies, always have clear advantage. The truth is that nobody really knew how to treat patients with this profile. Then I am fortunate that Internal Medicine is already included in my internship. The training that I completed a few years ago gave me tools. But every day I learn many different things - I learn something new "hour by hour". Many things are not linked to my specialty, but I am happy to learn them. I am really enjoying learning new treatments and therapies that I was not used to. But there are points in common, SARS-CoV-2 is a very thrombogenic disease, and thrombosis and haemostasis are the main specialization areas for immunohemotherapists. So, I think I ended up being able to evolve in my chosen area and to contribute to the team, since I have helped to manage the part of thrombotic and haemorrhagic complications of the patients in the infirmary. The feedback from colleagues and the exchange of ideas and knowledge have been very positive. I am very grateful to the team for giving me that opportunity as well. I find it interesting how such different areas intersect in the infirmary and complement each other, this was also a discovery. I learned to use a ventilator, manage non-invasive ventilation modes, use high-flow oxygen therapy and manage other types of therapies that I did not do in my daily life, how to put catheters and 'collect blood' every day - all of these dynamics that I haven't had for a long time. I have also learned to look after patients with various co-morbidities, in a perspective that is much less watertight than in a much more specific specialty like mine. Patients with various characteristics and much more comprehensive - all "settings" that require me to constant learning.

I am growing a lot as a doctor and I don't think I would grow so much and so fast if it weren't for this pandemic. It is also important to mention that all patients are very well looked after, because the entire therapeutic approach and strategy is always discussed and shared among the team and with more experienced people. They are the ones who guide us, help us to decide and share their knowledge allowing us to learn and grow.

This decision to integrate doctors from different areas in the wards, even if it was due to necessity, turned out to be very important. We have realized that it is useful to have a model where doctors of various specialties are daily with colleagues in the medical internship, as there is mutual assistance and a much more multidisciplinary management of the different aspects of the patient, facilitated by the co-existence of different areas of knowledge in the same physical space. It may be something that comes out of this pandemic - getting to know each other more, involving different specialties and starting to have a more multidisciplinary view. In addition, the integration of new elements was also very important because it made it possible to provide essential assistance to those who were on the ground and who could no longer stand alone.

And so experiences and different areas of Medicine are crossed. We all benefit.

Catarina’s last note:

I would like to thank UICIVE - Service of Medicine I, in particular Sector I-D where I was included for receiving me so well, and for helping me daily. Also thank my team at the Central ER. And finally, my colleagues and mentors from my ImmunoHemotherapy Unit.

Joana Sousa

Editorial Team