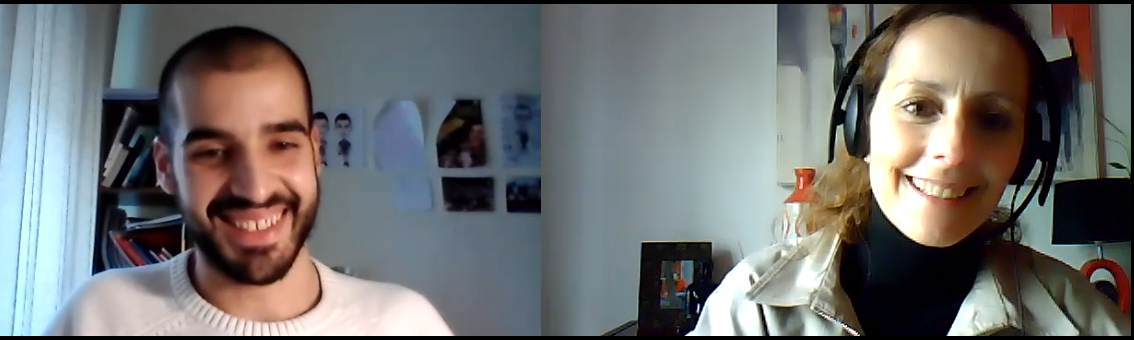

His joy is contagious. His good vibration permeates the senses, even without having said almost anything.

A few days ago, I had received a message about him, “You have to meet him, he wanted to go to the front line to treat patients infected with Covid. He speaks his mind out. You will like him!”.

I contacted him, a bit reticent because he may be tired. I am aware that he has to study and the pressure must not be easy as the last months have been the worst of the pandemic. He accepted right away when asked about a possible conversation, but only when it suited him. A few days later we were talking and during that hour that was over so quickly and made me laugh so much more than at any other time recently.

He says he is not the typical medical student, and I understand that during our conversation. He goes off track in a neat way. He always wanted to help others, and that is the predominant attitude in all his words. As a kid he wanted to be a firefighter, as he grew up he wore in his imagination the second uniform of the profession he wanted to follow, that of the military, influenced by his father and grandfather who were military and only later followed other professional paths. This does not mean he his hard or remote from affections. He always seized every opportunity to do volunteer work, always with the purpose of helping others. In year 11, he had his first contact with the Paediatric Hospital in Coimbra. He played with hospitalized children, many of them cancer patients. When he was in year 12, he realized that the profile that best suited him was that of a doctor and applied to the medical degree. Always thinking pragmatically and to the point, António Urbano is from a small village near Aveiro.

He initially applied to universities in the north, closer to home, but he was placed in one of his most distant options, the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon. Today he says that given what the experience brought him, it would have been a mistake not to come to FMUL. That was what made him leave Aveiro and move to the capital. But the first academic year was not easy. In an unknown land and with no older friends in the institution to support him, he went along alone, certainly containing much of the enthusiasm that we now notice in him and that sparks so much in his eyes. Today, he says that the Faculty friends are like brothers and that one of the strengths of this institution is the integration of those who arrive in the system and the practical and almost immediate access to patients, since the first year of this Master Degree. A year of adaptation, for him it was one of the worst. The pace of study required him to adapt in military fashion, without the right to great friendships, or much academic success, to which he was used in high school. Currently in year 6 of the Integrated Master Degree, he is doing an internship in Santa Maria Hospital, at Medicine 2C.

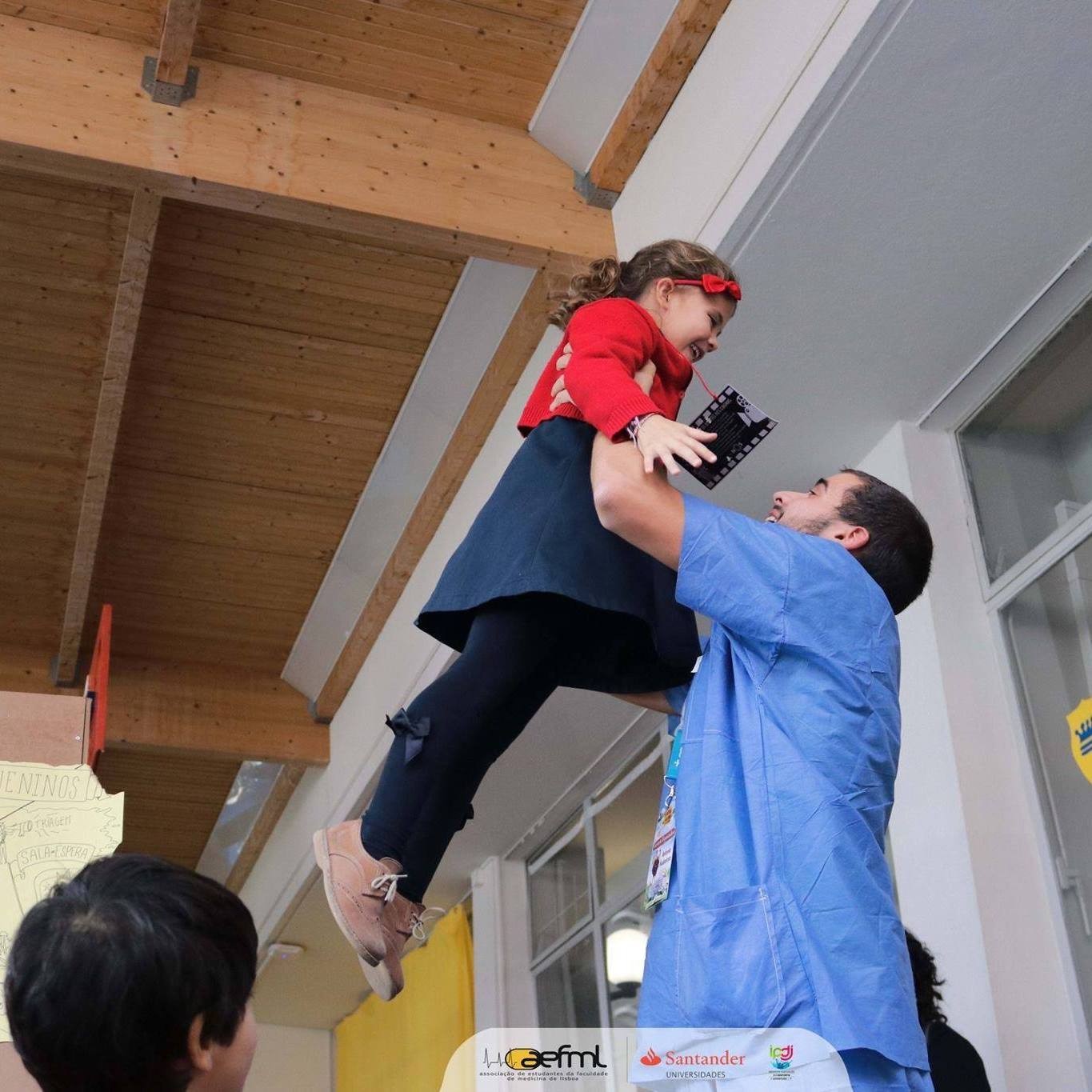

He was never part of the Students' Association (AEFML), but he was involved in several of its projects; he was part of a General Assembly board and for two years he was involved in one of the projects he liked the most, the Hospital for the Little Ones.

What motivated me to get to know António was his bravery and sense of mission towards the others, towards the Hospital and the University, and his willingness to provide care to patients infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, I quickly realized that children are the most important thing for him, above any other.

This explains António's internship in Neonatology, where he gave in to the temptation to accompany emergencies in the Intensive Care Unit of the same service. It was there that he became sure that this was his only path. The only one because if he does not enter Paediatrics at first, he will try again, because he will not give up on achieving this specialty that is his vocation.

He is persistent, obstinate and believes that if it is what he wants, then he will do his best to make it happen. This obstinacy, which António calls stubbornness, is largely due to his father's perseverance.

He is a caregiver and the confrontation with life ahead, or the end of it, does not make him shudder in his compassion for the others. In the last years of his paternal grandmother's life, he helped to take care of her, as if she were a child. Dealing with the degradation of the human body, of someone he loved, is a condition that he accepts as a cycle that is, for all of us, sequential. The notion that life has this path is very much supported by his resilience. He believes that crying due to the pain one feels does not build a path for the future and stalls time. "There is no time to stop and mourn" he says, without any harshness in these words.

Close friends say that António is as sincere as he is fun. In meetings with friends, he is an indispensable presence to liven up the people. He thanks his busy life, as he has such energy that he cannot stand sitting to watch even a movie until the end. He things it is too much wasted time, to the point that he plays it fast forward so that the movie finishes more quickly. Free time? He has it, but it is not for resting, it is for jogging, or doing exercise at home; running two hours without stopping in a marathon, was one of his desirable goals. Now more confined at home, he speaks for the two friends with whom he shares a house. There is no room for meditation without sound. Silence with oneself is difficult, it is almost uncomfortable.

It is disconcerting to realize how his athletic profile, perhaps due to 10 years of district handball, or to the swimming he still practices, can carry a baby in his arms so tenderly. The first time he held one was in the nursery. He took the baby on his lap to his mother and in the little time he carried him, he thought about the fragility of a life start that almost fitted in the palm of his hand.

Isabel do Carmo, the Endocrinology Professor who once worked at FMUL and was hospitalized with Covid at Santa Maria Hospital, was treated and monitored by the team that now received António Urbano, not to be treated, but for him to treat others. He started his internship in Medicine 2E on 18 January, when the lockdown started. He had voluntarily asked to go to the "COVID ward" and he was accepted, becoming one of the first students to volunteer to work there.

Previously, he had helped the teams of the Health24 line, but going to the field and to the front line was a goal he aspired to achieve. Faced with the scenario of going to a higher risk area and not yet having the right to a vaccine, something the Faculty Director fought for and insisted that these students should be vaccinated, did not stop his intention. He believes that one should not fear life. When he knows what he wants to do, he will fight for it until it happens.

How does a medical student manages his agenda? Perseverance is the answer. Each hospital day starts at 8 am and officially ends at 3 pm. Sometimes he stays on because there are days when “it is really necessary to continue to help”. After these hours on the ground, the medical team meets to analyse which Covid patients they are going to meet the next day and analyse their condition. After the final analysis by the specialist, Dr Patrícia Monteiro, a decision is made about the distribution of patients. Each person is responsible for an average of 2 to 3 patients, and for all the routines. Each day is totally different and unpredictable from the previous one. This is precisely what he writes in the patient’s medical register, around lunchtime, when a meeting is held again to discuss the therapies for the next day and assess what was experienced that morning. At 3:00 pm, the Medical Services come together to decide the distribution of Covid patients, according to their severity. As for António, he goes home and has lunch around 3:00 pm. He studies until 7 pm, in a count down to the National Access Exam, which will decide if he will get the much desired Paediatrics specialty. Tiredness is balanced to inspire him to study, as if listening to the voice that motivates him, “you have been working and helping all morning”. He then takes a break to train his body, resuming the training of the mind through study until 11 pm. Since the internships began (September), he feels his brain racing to review what he has to do the next day. Second by second, he goes through what he needs to do and check in his patients. He remembers them all, those he now has, and those who have been his patients. He projects this experience into the future, remembering who he wants to be. When I asked him "wouldn’t it be better to escape chaos while you can?", he replies with a smile that, "there are those who like to escape fire, but I am attracted by fire", a joke that he immediately associates with the fact that becoming a fireman was his first choice. In the face of danger, he always feels more compelled to move forward than to retreat. Calm is his dominant feature, losing control is not part of him and, in fact, he does not know what it would be like if he lost control. He believes that there is always something that can be done for others and, if possible, make them laugh. And as a sportsman, he is running the marathon in such a way that he holds on until the end. He does not want to sprint and use all his strength in just one moment. The internship with these Covid patients ends on 9 April, the day after his birthday.

An active protagonist not only in the happiness of his story, but wanting that of others to be lighter and happier, he nevertheless takes the present seriously, always looking at it as if it was a half full bottle.

In many years, António, who wants to become a grandfather, will tell his grandchildren that he was part of one of the most unpredictable moments in the history of the world, when an invisible virus bent all the economies to his will and required humility and resilience from them.

What made you volunteer to go to the area of greatest risk that currently exists in the Hospital?

António Urbano: At the risk of repeating myself, I always wanted to help a lot. Knowing that it was a national crisis and that the country was going through a difficult phase, my patriotism told me to provide a service and not just stand watching. I knew that in these areas of medicine the situation was chaotic and that those Covid patients would be more unstable and need more care and, as such, more people to help. The truth is that everything that is more connected to the Intensive Care areas arouses a great interest, and it was more of a motivation, to go to the "war ground". I knew I was going to learn a lot, because from the moment a service is overcrowded, it also means that there are many different cases, so there is more room for learning. At this moment (in Medicine 2C) I watch, every day, different cases, with patients with different scenarios and decompensating due to different new things. That also makes me learn, because every day is different.

Did you have any special preparation before going to the front line?

António Urbano: No. I volunteered and was asked to wait to be contacted and be given further information. Every day I hoped to be called, but there were no news. One day, a new year 6 student arrived and introduced herself to the position I had. That was how I realized that I was going to be transferred to the area I had asked for. I was "handed over" to Dr Patrícia Monteiro, our specialist in Medicine 2C, and I was delegated to her year 2 intern in the Internal Medicine specialty, Dr Henrique Barbacena. I thought I was going to be given some kind of formal explanation, but Henrique was very good and explained the most necessary information. I just had to shadow him and observe everything. He taught everything as I shadowed him. I am very happy, because I am in direct contact with the sick, and I see them and I write the records of those patients. Of course, it is Dr Patrícia who decides the therapy, but she allows me to give my opinion and collaborate. I have the dream of any intern, since I can put into practice everything I have learned and I am not just a spectator.

When Dr Henrique gave you this guided tour and introduced you to reality, what was it like?

António Urbano: I admit that I was anxious because it was something new and sudden. When I entered the Covid area for the first time, I found myself checking if I was dressing properly, how to put on the protection equipment, and asking myself if I was going to be infected, or not. I thought of everything and became a bit apprehensive.

Were you ashamed to ask questions, or did you feel you had to ask to know what to do?

António Urbano: I am not ashamed to ask, I am always asking and I am not afraid at all. I asked Henrique everything and he helped me with everything. As he explained, he always confirmed if I had understood. So my initial anxiety went away quickly. Now I feel very calm and nothing in my days makes me nervous. That does not invalidate the fact that there are patients with more complicated issues. And we do not always see the same patient, one day I see one, the following day another patient is there, and this forces us to adapt the routine and our role, whenever we meet someone new.

What is the severity level of patients in Medicine 2C?

António Urbano: We have several scenarios: patients who are stable, after having been very unstable, patients who are currently unstable and on the way to getting worse and in others it is the other way round. And even within unstable patients, there are varying levels of severity. It is so heterogeneous that it allows me to learn more, but we cannot be sure about what will happen.

Does being with patients that can be at many different stages in the disease cause cyclic anxiety?

António Urbano: It is a world apart. I had already done two internships in Santa Maria and it was very different. Before there was a lot of agitation, it is true, and now the reality has totally changed. The confusion is of a different type... However, the focus remains the same, on the patient. The profile of the patient has changed, the form of contact between the doctor and the patient has also changed, because now the doctors are all equipped and covered with masks and shields, but the care is the same. The patient feels equally supported, but the whole context has changed. One cannot imagine the happy face of those who are awake when they see us again arriving at the wards. They have a huge sense of gratitude, they thank us because they attribute their improved condition to our work, believing that if it weren't for us, they might not even be there anymore. The doctor/patient relationship is intact, it gives me immense satisfaction.

Does the patients' gratitude affect your emotions? When there is a reflection of gratitude, do you feel you have done your duty?

António Urbano: Yes... I speak for myself, I have always been pleased with the happiness mirrored in those who are feeling better. These cases help us to balance with the other group, the patients who are getting worse and sometimes die. This is my great contrast, in a single day, I see deaths and I immediately think of the other side of the coin, of those who are well and saved. I think this is the real reason why people become doctors, to save others.

Aren't you afraid that you could end up there in one of those beds?

António Urbano: I am not afraid for myself, but for my parents and grandparents. I see many patients who have my parents' age, even more that of my grandparents, and that bothers me. It makes us think a lot about our relatives. There is a scenario that is important to highlight, the coronavirus does not allow us to predict who is going to get worse, because we have quite old people recovering, and others much younger who die. Nothing of what we took for granted remains. I have had cases of patients who got in apparently well and then became very ill, and others who seemed they would not live to the next day, and survived.

Is dealing with this scenario challenging or scary?

António Urbano: I think that challenge and fear always go hand in hand. I tend to think that if there is something that is not scary, then it is not challenging either. Having a bit of fear is very challenging. There are patients for whom, of course, the affected part is the respiratory one, but in a good part of the people there, the respiratory side holds up, but become decompensated due to other pathologies. All kinds of pathologies may decompensate these people and that is always a challenge, because it takes us by surprise.

What we watch in the news is that hospitals are experiencing a kind of war scenario, where there are no longer human resources or technicians to support this situation. What is the real scenario out there? Chaos or apparent calm?

António Urbano: The first impression is that it is a normal Internal Medicine service. But all beds are full and we know that, the second one is released, it will be immediately taken again. There are patients to occupy any vacant bed. The worst scenario is in the containers where patients are first admitted. I have volunteered to go there, I want to help my colleagues, understand how to deal with chaos. There is a lack of specialist doctors, there are many patients with many pathologies, many decompensated patients. The situation in our Medicine 2C is more reassuring, because at least each patient is in his bed. At the same time, when patients start to decompensate, the whole service helps. It was not like that before, whereas one in twenty patients decompensated. Now most of those twenty patients decompensate at some point. There is always a lot of action, new problems. It's all very unpredictable.

Are there enough human resources in your area?

António Urbano: We have managed to have everything. However, we have only one specialist for our 20 patients. But we did it because we have interns and the whole group in general.

How do you think you are going to deal with an area as delicate as Paediatrics, where children seem to have no middle ground?. Either they recover very quickly, or they get really sick.

António Urbano: It is funny how I have had this discussion with my colleagues and this lack of middle ground, which demoralizes some, is what motivates me the most. Children have this special thing, it seems to them that it is magical and everything goes well, they do not realize when they are sick and when things go away, they don’t even think about it anymore. Even in situations when the child is having a difficult time and may have an unhappy outcome, that side also motivates me to do everything so that the bad outcome does not occur. And even if it is to face this bad outcome, then let me be there with this child.

We often think that they don't understand what is going on and they do; other times they don't understand what is going on with them and we have to know how to explain it to them, and that is very challenging. Even working with a new-born is very rewarding because we are helping to keep that life going, we are helping it to reach the future. This is the view that I have of Paediatrics, it takes care of the present, to offer a giant future. We hold them in our arms and there is magic, because everything is unpredictable in children. My view of Paediatrics, now that I am in Internal Medicine and I see situations when I think that we can no longer do anything for people and that we can only maintain a therapy, gains more relevance and magic in my life.

You told me that after this internship you will work at Beatriz Ângelo and Garcia de Orta Hospitals and then end up at a Health Centre. Your work in Santa Maria will end in April. You're going to miss this place of chaos, aren't you?

António Urbano: I will miss it 100%. Santa Maria is my home, often my first home. I have spent six years at Santa Maria and the Faculty. I have lived among wards, classes, I know every corridor, every corner. This place is very special, despite being an old Hospital. This place, this Faculty, are my home.

Joana Sousa

Editorial Team