"As long as we are alive, we cannot escape masks and names. We are inseparable from our fictions - our features".

Octavio Paz, (1914-1998), Mexican writer and poet

Masks have been used since ancient times in the most diverse forms, made of different materials and with different purposes. It is currently used by all of us, in this time of pandemic, as health protection.

A year ago, it would be hard to imagine having to go out on the street with our mouth and nose covered, although masks have been used for a long time as prevention for various contagious diseases that have devastated the most eastern region of the globe in recent decades and as protection against the high level of pollution in several Asian countries, such as China.

After a few months of lockdown earlier this year, the mask has suddenly become, in Western countries, one of the essential and preventive accessories, in addition to sanitising gel, protecting us from the latest coronavirus so that we can return to normality as well as possible. The Covid-19 pandemic made wearing masks a global practice.

In addition to being a sanitary protector, this new form of combating contagion quickly became a fashion accessory. Many made masks in fabric and artisanal form after having viewed some of the videos available on the Internet. The designers also included masks of various colours and models in their collections, as happened on the catwalk of ModaLisboa in the beginning of February this year.

The origin of the word mask is unknown. Some believe that it comes from ancient Latin (“masca” or “mascus”, meaning “spectrum”), Arabic (“maskharah”, synonymous with “clown” and “disguise”, and the verb sakhira, “to ridicule”), or from the Hebrew (“masecha”, which means “he scoffed, ridiculed”).

Another version refers that the Portuguese "mask" comes from the Italian word “maschera”. This word expanded throughout Europe, included in many languages such as "mask" in English or "maska" in Polish.

The use of masks is one of the oldest human practices, used by countless civilizations throughout history, allowing experiments to be carried out in the human imagination. Considered as a sacred object, the mask had different functions. Each mask had a different purpose and most of the time it was considered to be a symbol for social organization, the notion of good and evil and also of life and death.

According to its origin, there are several types of masks and each has its own purpose, although it has always had a symbolic character. The mask always represents something to someone and can be better understood by individuals who belong to the same culture.

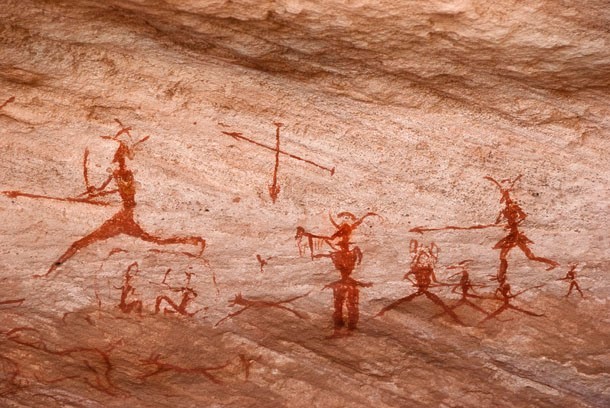

Archaeological records that have reached us show the use of masks in cave paintings, perhaps used for a higher entity to intercede for the practice of hunting to be successful, but also as rites of passage, magical rituals, communication with the gods and ancestors, freedom of speech or entertainment behaviour. The use of the first masks by men occurred in 9.000 B.C.

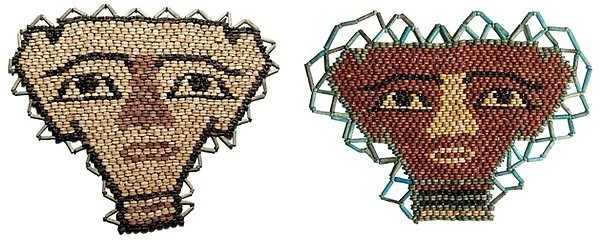

Coming from various continents like Asia, Africa, Europe, America or Ancient Egypt, the mask has always been present in different cultures and has played different roles throughout history. It has propitiated the future of societies, leading them to dissociate good from evil, the sacred from the profane, or life from death. They were ornamented with different materials like shells, wood, metals, skins, fabric or corn straw.

In China, masks were used to chase away evil spirits, while in Ancient Egypt and Greece, masks were placed on the face of the deceased in order to guide them in the passage to eternal life.

They were built of fabric or plaster and then painted. For the most important people, precious metals such as gold and silver were used.

As an example, we have the most famous pharaoh Tutankhamun (1350 BC), who had the richest funerary mask that would transport him to eternity confident and in good health.

In ancient Greece, theatrical masks appeared during the Dionisio festivities, god of wine and fertility. They showed an exaggerated expression of each character. They were used in drama rituals and projected in a size that would allow the presence of the actor as well as his voice to be amplified through a device like a “megaphone”.

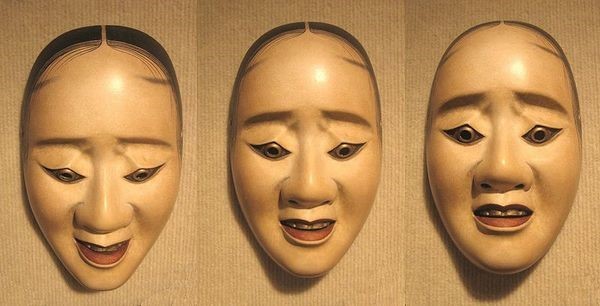

The Japanese theatre No, a mixture of singing, pantomime, music and poetry, is characterized by 125 varieties of masks, constituting five types. They are made of wood, varnished, gilded and painted, according to the characteristics of the characters, such as violence or honesty.

At a Bal Masqué (traditional European masquerade), the use of a mask was mandatory. Masked courtiers played games, overflowing their impulses and freeing them from social norms.

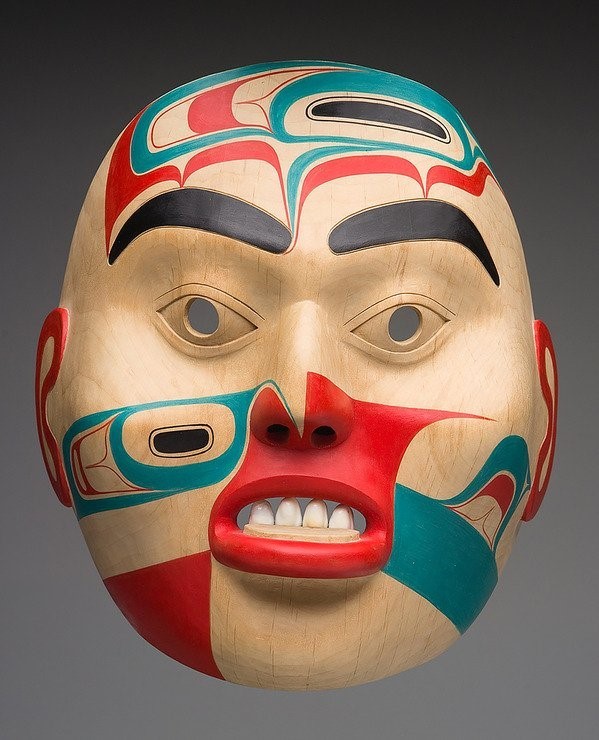

Also Eskimos, in Alaska, believed that each person had a double existence and could change to the form of man or animal, as wished. Their masks were made of two faces, one of a human being and the other of an animal. During the festivities, the outer mask was raised showing the other mask.

During the Middle Ages, masks became a profane object, only used to honour other gods. Its use was linked to popular manifestations outside Christianity, reappearing in the late Middle Ages, mainly in Italy, where the Venice masks started to be decorative pieces. They were used by the "court jesters" and became the main economic source in the region. Later, the masks became characters from the Commedia dell'arte, such as Harlequin, Pulcinella, Pierrot and Columbine.

This improvised popular theatre was held in public squares where they ridiculed the customs of the nobles of the time. Later, these characters inspired the Venetian Carnival that would last until the end of the 18th century. With the fall of the Republic of Venice, tradition fell into disuse and ended up disappearing.

Various artistic creations in different formats and functions originated in masks, as in the cinema, theatre, religious rituals and in parties such as the Carnival of Venice (Italy), and the tragedy and comedy that marked some renowned painters in the early years of the 20th century, like Pablo Picasso, George Braque, Henri Matisse or André Derain. However, theatre was the art that most explored the magic of masks.

Even nowadays, we use masks in some parties like Halloween and Carnival. In Brazil, the Indians pray to the gods for good harvests with huge straw masks. Also in Portugal, in the region of Trás-os-Montes, the rattleman wears the devil's mask and makes his door to door collection. The use of masks is related to religiosity and issues such as the exploitation of the poorest, representing the exploited and the oppressed.

Over the centuries, there has always been a need, at certain times, to protect the head, where the main senses are located, such as vision, hearing and communication. For example, aviator glasses or masks that protect against disease. In Europe, the medieval knight had a helmet that protected his head during the fighting. Japanese soldiers also had masks that revealed the lineage the knight belonged to.

Christos Lynteris, professor at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and specialist in the history of medical masks, says that paintings from the Renaissance period (between 1300 and 1600) show people covering their noses with tissues to prevent disease. Also works of art of French origin, from around 1720 when the bubonic plague spread, show people and gravediggers handling bodies with a cloth around their faces.

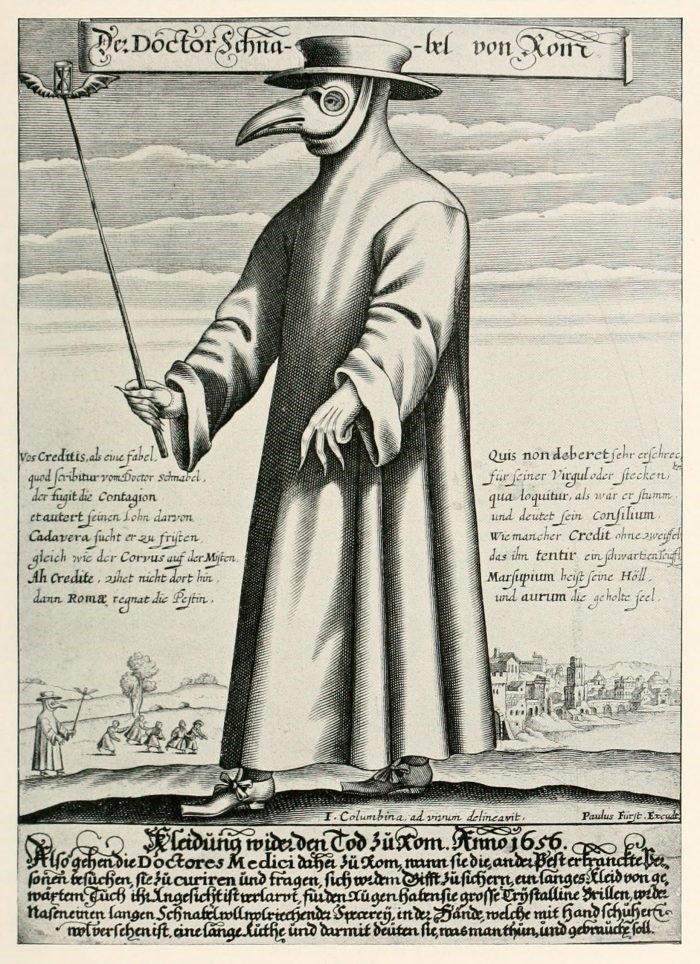

The mask used in ancient times underwent an astonishing change compared to the mask used to combat the black plague or bubonic plague, which afflicted Europe and Asia between the 14th and 18th centuries and killed 200 million people.

At that time, the medical suit was adapted according to the knowledge gained. It consisted of a leather overcoat from head to toe, leather gloves, pants, boots and a wide-brimmed hat. The bird-shaped mask was developed by French doctor Charles de Lorme, based on an Ancient Greek theory that referred to unpleasant odours, or "bad air", like that of rotten carcasses or foods that caused disease. It consisted of circular glasses made of thick glass and two small holes in the huge beak where straw and various aromatic herbs were placed to filter the air and prevent the doctor from contracting the disease. It was mistakenly thought that by protecting themselves from smell, they also protected themselves from disease. These masks have become quite popular since their invention and are still used in the cinema, literature and video games.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was absence of the plagues that affected the populations in previous centuries and the use of masks also disappeared.

Both Pliny the Elder and Leonardo da Vinci believed that inhaling certain airborne particles and dust could be harmful.

At the end of the 19th century, in 1897, Paul Berger, of French origin, upon discovering that saliva could contain disease-causing bacteria, became one of the first surgeons to use the face mask during surgery.

The use of masks was not intended to protect doctors or patients from possible infections, but to prevent droplets from spreading when sneezing or coughing during surgery.

The mask used by Berger was attached over the nose and made of six layers of gauze, and the bottom edge was sewn on top of his sterilized linen apron. However, it would take several decades for doctors to start wearing face masks.

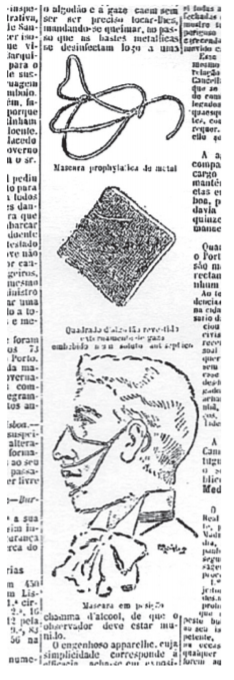

An important demonstration of the creativity of the Portuguese medical profession was the invention of the prophylactic mask, created by doctor Afonso de Lemos in 1899, for doctors and nurses to use in the observation and treatment of patients during the bubonic plague. Facial masks were disseminated and started to be used only in 1918, during the flu epidemic.

For about 50 years, doctors fought against wearing masks. In 1905, physician Alice Hamilton published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, criticizing doctors for not wearing masks during operations, even in the most advanced medical schools.

British physician Berkeley Moynihan, in one of his books published in 1906, defended the use of facial masks and condemned doctors who worked without them. In his book he said that "... the bacteria expelled from a person's mouth is worse than the worst sewage in London".

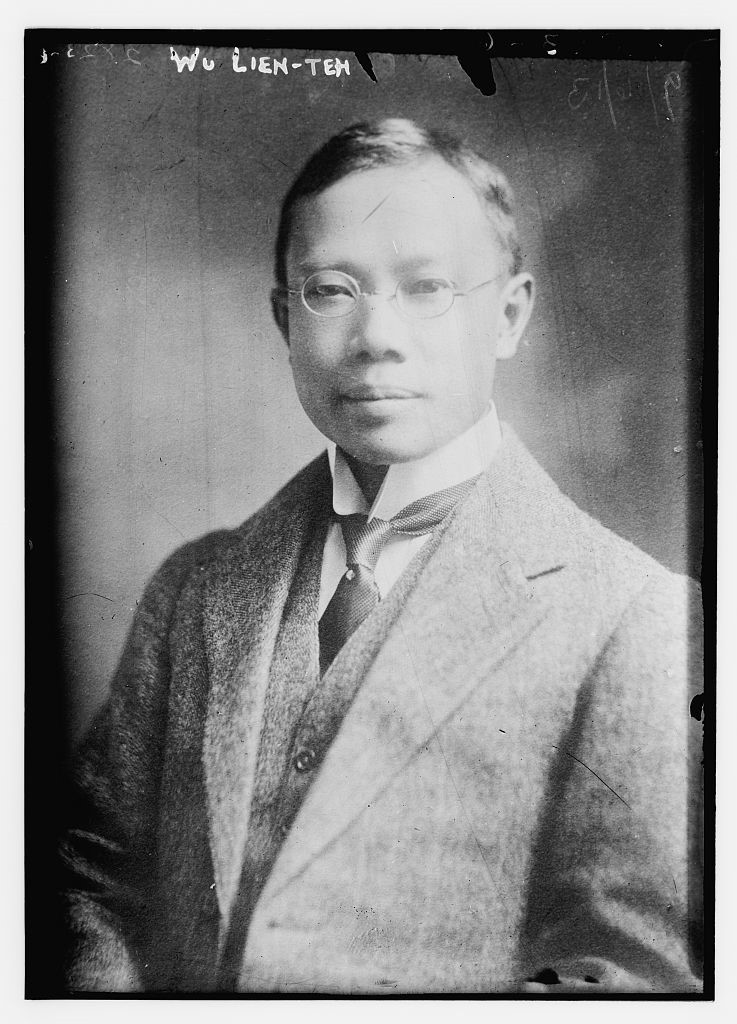

The use of facial masks became popular after a terrible plague in Manchuria (northern China) in the first decade of the 20th century. It had a 100% death rate in 48 hours and caused 60.000 victims in four months. Cambridge-educated Chinese doctor Wu Lien-teh was called to the region to analyse the situation, ordering all doctors, nurses and even cemetery officials to wear face masks after an autopsy, where he said the disease was not transmitted by fleas, as was thought, but by air.

The medical community ridiculed Wu for this initiative. Wearing the surgical masks used in Europe, Wu improved them by adding more layers of filter material. Although other doctors started to develop their own masks, Wu Lien-teh's masks became evident, after several tests, as the one that most protected from bacteria. It was also considered to be the cheapest because the materials used were more easily available. In view of these characteristics, the production of Wu masks soared and, through the press, became popular all over the world. They became a symbol of scientific progress and were worn by doctors, the army and the general population.

When in 1918 the wrongly named “Spanish flu” appeared, Wu's masks gained enormous importance. They became known worldwide and helped to prevent the epidemic from spreading, despite the very high number of victims.

During the first half of the 20th century, several styles of masks were developed, usually made of cotton gauze with a metal frame.

In the 1960s, disposable masks became very popular. In 1972, Peter Tsai invented the N95 respiratory mask, doubling its capacity in 2018. It has been one of the most used until today. It is assumed that this mask is inspired by another one invented by Wu Lien-teh, who was very close to winning a Nobel Prize.

In view of the historical moment that we are currently experiencing, museums around the world began the work of “keeping the present” early in the pandemic, so that in future there will be exhibitions that will allow these exhibits to be admired by people who have not had this experience, or may wish to remember it.

Museums, as “guardians of memory”, are not limited to gathering objects from reality, they also collect testimonials from people who experienced it, images, some of them obtained through drones, showing deserted cities, filming or photographs, to enable the reconstruction of an era, taking advantage of technological resources that allow the recording of memory to be very faithful to reality.

Some international museums are receiving donations from the population, such as rainbow drawings or calls made through the Zoom platform. The National Museum of Cologne was offered a crocheted representation of the coronavirus.

The Covid-19 Ad Memoriam Institute was created in France with the aim of collecting oral testimonials from the population, so that it is possible to make a collective reflection as the researchers affirm that one of the effects of the pandemic is a “great anthropological rupture”.

In the US, the Autry Museum has a collection of nearly 200 items, among which "the diary of a 6 year old child who, in March, drew a sad face because he was unable to leave his home".

Also in Portugal, at the beginning of March, the Pharmacy Museum in Lisbon collected a swab offered by São João Hospital, in Porto, the first to perform this type of tests. The museum also houses the donated prototype of the first Portuguese ventilator, the radiography of the first pharmacist admitted to intensive care, the photograph of the new coronavirus taken by a Portuguese laboratory, hospital equipment like portable tests and shields, and the announcement of the state of emergency by Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa on 18 March or the homemade mask donated by Bento Rodrigues offered by a neighbour who made it and left it at his door.

The Museum of Natural History and Science of the University of Porto already has a collection on the pandemic "Collection as Response to SARS-CoV-2". It includes shields, tests and masks of various models and materials, including one made of cork.

The Health Museum of the National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge in Lisbon also has an exhibition on this theme in mind, still in the planning stage. The medical material needed today and all the materials donated and related to the pandemic will remain in its collection.

References:

- A BREVE HISTÓRIA DA MÁSCARA. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://canalhistoria.pt/blogue/a-breve-historia-da-mascara/

- Uma breve história das máscaras faciais médicas. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://gizmodo.uol.com.br/uma-breve-historia-das-mascaras-faciais-medicas/

- Conheça a história de origem da máscara N95, símbolo da pandemia de coronavírus. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://epocanegocios.globo.com/Mundo/noticia/2020/03/conheca-historia-de-origem-da-mascara-n95-simbolo-da-pandemia-de-coronavirus.html

- Covid-19: Andar de máscara na rua é o novo normal. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://visao.sapo.pt/atualidade/sociedade/2020-04-17-covid-19-andar-de-mascara-na-rua-e-o-novo-normal/#&gid=0&pid=1

- A história das máscaras. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://student.dei.uc.pt/~jsilva/movimento/chc/galeria/exposicoes/mascaras/historia.html

- Máscaras, uma proteção com passado. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://www.jn.pt/mundo/mascaras-uma-protecao-com-passado-11951924.html

- O médico português que inventou a primeira máscara na peste do Porto em 1899. Acedido em 09/09/2020https://observador.pt/programas/convidado-extra/da-fome-da-peste-e-da-guerra-livrai-nos-senhor/

- A ORIGEM DA MÁSCARA. Acedido em 09/09/2020 http://lounge.obviousmag.org/anna_anjos/2013/11/a-origem-da-mascara.html

- Porque usámos máscaras ao longo dos tempos? Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://expresso.pt/cultura/2020-07-05-Porque-usamos-mascaras-ao-longo-dos-tempos-

- De rituais à proteção: história das máscaras ao longo do tempo. Acedido em 09/09/2020 https://ndmais.com.br/saude/de-rituais-a-protecao-historia-das-mascaras-ao-longo-do-tempo/

Lurdes Barata

Library and Information Area

Editorial Team