“Death is the curve on the road. To die is just not to be seen... ”

In: Poemas Completos (Complete Poems) de (by) Alberto Caeiro. Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935)

In all cultures and since the most ancient times, man tries to deceive and resist death, seeking immortality, without success. We have as an example the very old litany, that starts like this:

“No one escapes death/Neither the king nor the pope/But I escape /I buy a pan/It costs me a penny/I get inside it/And I cover myself very well/Then death passes by and says: - knock knock! Who's there?…/- Here, nobody is here. Goodbye, gentlemen, be well”.

When we least expect it, death comes, without mercy, to meet us, and it always appears without warning. No one, neither those who leave nor those who stay, is prepared, nor will we ever be trained for this meeting. One moment we are among others and the next moment we can be away from everyone, forever.

The sacred scriptures state that “There is a time for everything. There is time to be born and time to die ”.

What is most certain, from the moment we are born, is our demise. The human being is the only living being who is really aware of the existence of death, of his finitude. None of us, whatever our physical or social condition, cannot escape death. Whereas many can have a long life, there are also many who receive the visit of death too early, whether due to natural causes, without it being their fault or intentional.

For those who stay, the question always arises. Why? We think that death is very unfair. So many times, those who go still had many dreams, projects and promises to fulfil. How many times are projects started but never finished because they are interrupted by death? What was the use of sacrifices, dedication, hard work, or having financial power, influence or fame at one’s disposal?

If for some of us the interruption of life can be caused by an illness, an accident around the corner, an unpredictable and abrupt event, there are still those who choose the moment to leave, driven by disorders such as depression, disappointment, disillusionment, unhappiness or “simply” because they are fed-up with life.

Even if we want to live as best as possible, we face the hustle and bustle of our daily lives when it is difficult for us to separate periods of work, rest, or some family moments. Still, at any time death can reap the plans we had envisioned.

If some of us can desire death as a means of liberation and escape, for others there is a fear of dying, especially if death is accompanied by pain and humiliation, particularly if surrounded by countless medical devices introduced into their bodies and often against the will of the sick themselves. With the huge development of Medicine combined with technology, we have seen in the last centuries that health professionals try to prolong the lives of those who suffer, even for a few more hours, days or weeks.

There are aches and pains. There are pains that make sense, like childbirth pain, when a new life is born. However, there are other pains that are useless, unnecessary, when we know in advance what the outcome will be.

For Western culture, death is shrouded in mysteries, fears and doubts, but also accompanied by pain and suffering. Although we know that it is the only certainty we have in our life, our behaviour in the face of death is still considered taboo, we deny it, as if it did not exist, we try to avoid talking about it, as if not to attract it, although we never forget it.

The relationship between human beings and the most unwanted of the unwanted has changed over time and been demonstrated through various forms of art such as architecture, tomb sculptures, the practice of rituals, allied with curiosity, restlessness and fear. Since its appearance, funerary sculptures represent death resting as if in a long sleep accompanied by the advice “Rest in peace”.

Studies reveal that after dying, prehistoric man was left at the mercy of animals, while in the Neanderthal period it was usual to bury the dead. They were buried in squatters, in open cavities in the rocks, accompanied by various offerings and objects that had belonged to the deceased. Finally, they were covered by stones.

In the following period, the Cro-Magnons, who believed in life beyond death, placed their dead lying or in a foetal position, also taking offerings, believing that they were necessary in the Afterlife.

The Mesolithic man built oval graves and the dead were adorned with objects made of shells and animal teeth and covered with stones.

In the Neolithic and Bronze Age, collective graves were introduced and the first funerary monuments appeared.

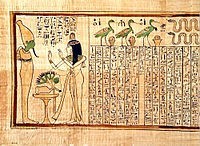

The people in Ancient Egypt wanted to achieve eternal life through the use of spells and rituals. They believed that the soul, "Ka", continued to exist after death and the objects that had been used by the deceased were placed in the graves. Without these, the soul could not make the connection with the physical body that was supposed to be in good condition through mummification. The “Book of the Dead”, an Egyptian legacy and the oldest illustrated book in the world, describes the praises that the Egyptians had towards their dead, including hymns, prayers and magical texts of protection. The Egyptians believed that whoever took the book to the grave would find the salvation of the soul, as it contained guidance on how to reach the Afterlife.

The Romans were the first to introduce sculptures into the tombs, in order to honour their loved ones. They practiced cremation, which was seen as a new stage for their dead.

In Greco-Roman society, there were two conditions for people who died. Anonymous people and those who belonged to society in general were cremated and later placed in mass graves. Those who belonged to high society were considered heroes and immortal after the completion of a ceremony of great pomp.

In the face of death, Greek society performed various rituals, from the preparation to the burial of the corpse, so that the soul would find the path that would take it to the Afterlife, to the practices that absorbed the contamination and impurities left by death. One of these rituals was to place a vase of crystals on the doorstep.

During the Middle Ages, there were two distinct representations of Man before Death, in the High Middle Ages (5th-mid-12th centuries) and in the Low Middle Ages (12th-15th centuries).

In the High Middle Ages, death had a familiar, intimate concept and the act of dying was seen in a very natural way. The dying person, assuming that death was near, asked for forgiveness for his sins in order to obtain the necessary peace that would take him to paradise. Whoever did not ask for forgiveness for his failures, or who succumbed to sudden death (had not had the opportunity to redeem himself), would go to hell. And going to hell was one of the greatest fears of medieval man.

The dead were draped in shrouds. Those who were poor were buried in the courtyards of the churches, while the rich were buried inside them, believing that the saints protected them from going to hell. As there was great proximity between man from the medieval era and death, festivities and meetings were held in cemeteries and churches.

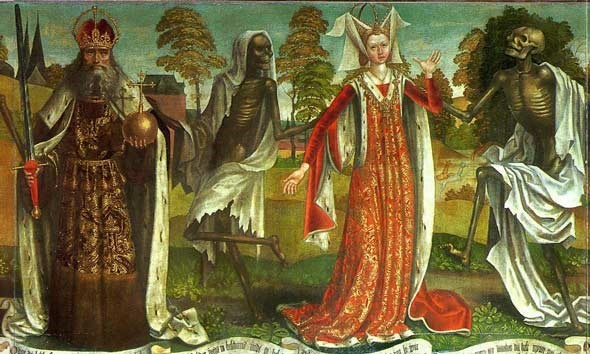

In the Low Middle Ages, due to the evolution of the power exercised by the Church, a new concept of death arose. Death came to be characterized as the end of time and emerged as a theme in European literature and paintings, characterized as a mark of horror, rot and fear. It was around this time that the figure of the skeleton with the scythe appeared as a symbol of death. For the medieval population, death was a punishment from God, it was almost always present in their lives due to the continuous wars, the black plague which, at that time, spread throughout Europe and almost decimated 1/3 of the population, until the arrival of the Inquisition, which condemned the infidels.

With the scientific revolutions that took place from the 15th century onwards, man had a new understanding of death, making him more rational and with new knowledge. Death came to be seen not as an intimate thing, but as a bad thing.

Later (18th and 19th centuries), the concept of dying was considered dirty, contaminating, opposing the concept of hygiene and the sanitary means that were implemented in public health, after the growth of the bourgeoisie as a result of the industrial revolution.

During the eighteenth century, the expression euthanasia, a term coined by encyclopaedist philosophers, arose with the intention of providing the individual with a painless death, in order to alleviate the suffering caused by an incurable or painful disease, usually performed by a health professional following a request expressed by the patient himself.

The word euthanasia derives from the Greek "eu", which means good, and "tanathos", which means "death", that is, "good death". It indicates the attitude of taking someone's life at his request, in order to end his suffering.

Euthanasia can be classified as voluntary and involuntary. It is voluntary when the person, consciously, expresses the desire to die and asks for help from a health professional to perform this procedure. The involuntary form is when the person is unable to give consent for a given treatment and that decision is given by another person, usually fulfilling the desire previously expressed by the patient himself in this regard.

Euthanasia differs from assisted suicide, inasmuch as this is the act of providing the patient with the means to commit suicide. The main reasons for patients to request euthanasia are the intense, atrocious and unbearable pain they feel due to the incurable disease they suffer from, and the continuous decrease in quality of life due to physical conditions (paralysis, incontinence, shortness of breath, difficulty in breathing, swallowing, vomiting) or psychological factors (depression, fear of losing control of the body, dignity and independence).

Euthanasia can also be active and passive. It is considered active when the act of ending the patient's life is done deliberately (for example, injecting an overdose of sedatives). Passive euthanasia consists of not carrying out or interrupting the treatment necessary for the patient's survival.

Today, death is seen as a kind of mystery, one avoids talking about it and it haunts those who hear about it.

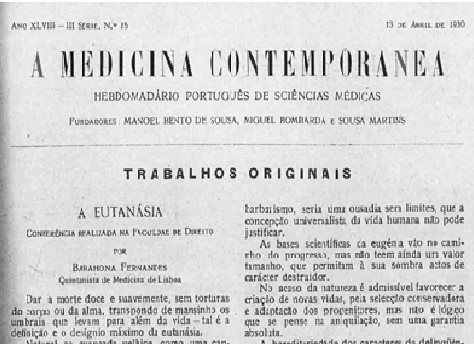

In Portugal, the first conference on euthanasia took place at the Faculty of Law of Lisbon in cooperation with the Students’ Association of the Faculty of Medicine of Lisbon, at the beginning of April 1930, where Professor Barahona Fernandes, at the time a year 5 medical student, gave the speech “Euthanasia”, which was published at the same time in the magazine “A Medicina Contemporânea”.

He addressed the medico-legal implications of this practice and exposed the various steps and projects for euthanasia about to be legalized in several European countries, as well as various approaches about the practice and attempts to avoid euthanasia. These come from very old times, with Aristotle and Plato. There is also a reference that Plinius also questioned its use.

He also referred to the rituals practiced by the Celtic peoples and other barbaric peoples in Burma in the face of death, such as “hanging the sick without salvation”. The Scandinavian peoples put an end to the lives of the elders, as well as the sick who burdened them. In Portugal, there is an allusion to the “furtadelas, the midnight broth, a legendary drug that would take care of the incurable”.

The first efforts to legalize euthanasia occurred in 1903 in the United States of America. However "the desire was not met because of the great protests that arose". With the same purpose, several projects were carried out in other countries such as Germany, Italy and England, where the topic was discussed in numerous scientific societies.

Euthanasia was a topic approached by several writers and playwrights in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Benson in England, René Bretoin in France and Guido de Verona in Italy, which gave rise to tragedies and novels. Binet-Saugeet, in his book “L’art de mourir”, openly defended homicide-suicide.

Currently, only three European countries have legalized the practice of euthanasia: The Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.

In April 2002, the Netherlands was the first country to legalize and regulate euthanasia. This practice must be exercised by a doctor, at the request of the patient, who must be convinced, in full awareness and lucidity, of suffering from an incurable disease and being in a terminal state and in painful suffering. In the impossibility of the patient being in possession of his mental faculties, it is necessary to know that the patient has previously expressed his will. In cases where the patients are children under the age of 12 years, the consent of the parents must be given.

Also in 2002, Belgium legalized euthanasia and amended it in 2014, allowing this practice to all patients of any age, as long as they suffer from incurable disease and have the ability to understand.

The decision to legalize child euthanasia was a controversial decision, which generated criticism both at home and abroad. In these cases, the cases are followed up by a special commission, by the parents, by doctors and child psychologists. It was first applied in 2016.

In Switzerland, euthanasia is illegal although assisted suicide is accepted as long as the terminal patient is in intolerable and irreversible suffering. It also provides for the creation of companies that support patients in these practices, such as associations like Exit and Dignitas, the latter being a non-profit organization. According to Jornal de Notícias, in 2016 there were 20 Portuguese registered in Dignitas and between 2009 and 2019 seven Portuguese obtained their support. Last year, this association, the only one in the world to support patients from different countries, supported 256 patients of different nationalities to end their lives.

The third country in the European Union to legalize euthanasia was Luxembourg, which created a law stating that it is not condemnable for a doctor to "respond to a request for euthanasia or assisted suicide".

There are still other countries where euthanasia is allowed, as in some North American states (Oregon, Vermont, California and Montana) and Canada. In Uruguay, Peru and Colombia, euthanasia is considered a “pious homicide” and for this reason it is grants “judicial pardon”.

Also in Australia, euthanasia has been allowed for terminally ill patients since mid-2019.

In New Zealand, a referendum is scheduled to decide on the entry into force of the new euthanasia law that began to be discussed in 2017.

Also in Spain, on 12 February this year, the legislative process for the decriminalization of euthanasia began.

In Portugal, for some years now, euthanasia has been the subject of studies, articles published in the media, law draft proposals, referendum requests, heated debates, petitions and popular protests, perfectly understandable, in view of the various personal, religious and cultural conceptions involved in addressing this issue.

With the development of medicine and the new technologies, there is also a new reality, a new ethical behaviour in the face of dying.

It was found that between the 1970s and 2005 the act of dying in hospital in our country increased from less than 20% to almost 60% per year. This change is not understood as a “simple change of place, but as a denial of place to those who die”. In view of this reality, it is necessary and urgent to have a deeper ethical approach to the issues surrounding human death, a greater understanding of hospitals as an integral existential place and an improvement in palliative care as an encounter of medicine with its humanist matrix.

As Father José Nuno Ferreira da Silva, hospital chaplain and author of the doctoral thesis “A morte e o morrer entre o deslugar e o lugar” (“Death and dying between the non-place and the place”), published in a book in 2012, people in Portuguese society die badly and profound change is essential if we are to die better in our country. It is necessary, both in hospitals and in the institutions for the elderly, "to change structures, create regulations and, above all, to provide specialized training to health professionals so that they learn how to deal with death, which happens more and more in hospitals". It is essential that health professionals retain skills so that, on a daily basis, “they can accompany people in suffering, people dying and people losing those who die”.

This topic was discussed in the Portuguese Parliament three years ago, when some political parties expressed their opposition, while others were in favour of the legalization of euthanasia and assisted suicide, warning that this can only be done in health establishments or at the home of the sick.

Also around that time, several movements came out in favour of or against euthanasia, like the National Council of Ethics for the Life Sciences (CNECV). In 2017, it organized 12 public debates in several Portuguese cities sponsored by the Presidency of the Republic, with the title Deciding about the end of life. The Stop Euthanasia Movement and the Right to Die with Dignity Movement also manifested themselves. The first against euthanasia and the second in favour of assisted death.

Currently, euthanasia is at the centre of an intense public debate with several considerations, both religious and ethical and practical, which originate from different perspectives on the meaning and value of human life.

Fig. 12 – Posters for or against Euthanasia

Opinions are divided on this topic. There are people who are in favour of euthanasia and there are others who disagree with such a practice.

Those in favour of euthanasia admit that this is the means to prevent patients who suffer from incurable diseases and who are in a terminal phase or without quality of life, from suffering intolerable pain and become increasingly more degraded. They also argue that with euthanasia, the patient dies in a dignified and, therefore, painless way.

When the patient has an incurable disease and becomes a prisoner of his own body, dependent on meeting the most basic needs, the fear of being alone or of becoming a burden to those around him, leads him to revolt against his situation and to ask for the right to die with dignity.

In order to choose, or not, this option, each person must be able to decide for himself, to choose a softer and less painful death instead of having a slow and unbearable suffering. The death choice cannot be made without thinking and must be contextualized and thought through according to several biological, family, social, cultural, economic and psychological components, reflecting the true autonomy of the individual without influences outside his will.

Opponents of decriminalizing euthanasia point to several political, social, ethical and religious reasons. From a legal point of view, the Penal Code currently in force in Portugal does not specify the crime of euthanasia. It condemns any act that puts an end to a life, and voluntary homicide, suicide assistance or homicide, even if at the victim's request or out of compassion, can be punished criminally.

From the point of view of medical ethics and according to the Hippocratic oath, in which he considers life as a sacred gift, over which the doctor cannot be a judge of someone's life or death, euthanasia is a crime. The doctor, in order to fulfil the Hippocratic oath, must assist any patient by providing him with all the means necessary for his subsistence. In addition, it turns out that, often, individuals who are disillusioned with traditional medicine, resort to alternative medicines and are able to heal themselves.

From a religious perspective, euthanasia is a method that takes an individual's life and only God has that right. Human life is "sacred" and dignity is intrinsic to natural death.

After the meeting of the Permanent Council of the Episcopal Conference held this year in Fátima, the bishops called on health professionals not to give in to acts such as euthanasia, assisted suicide "or the suppression of life", even in cases of irreversible disease.

Manuel Barbosa, secretary of the Portuguese Episcopal Conference (CEP), said that "the defence of palliative care must continue. Palliative care must be the most worthy option to fight against euthanasia".

At the same time, about 500 health professionals signed a public petition to decriminalize assisted death, launched by the Civic Movement Right to Die with Dignity.

Also the archbishop of Braga, Jorge Ortiga, considered that life "is inviolable" and palliative care "is the only answer to guarantee a dignified death".

In a text published in Expresso magazine in February 2020, Cardinal José Tolentino Mendonça stated "it is not life that must be subject to the circumstances (...) of each time, but the circumstances must be at the service of life. The real mission that belongs to politics is the indefatigable support of life". "Our societies have to ask themselves if they have already done everything they could do to promote and support life, especially those who are more fragile".

On 20 February this year, MPs approved the decriminalization of euthanasia and the regularization of medically assisted death in Portugal. The debate will continue at the Parliamentary Committee. In the future, there will be a final vote and then it will go to the President of the Republic.

However, euthanasia remains a taboo in our society. Although we know that we are not eternal, talking about the end of life causes bitterness and suffering. With the enormous technological progress that we have witnessed, the average life expectancy that has doubled during the last century, we can understand that our amortality (ability to prolong life) is no longer just a dream and is on our horizon. Science tells us that it is merely some technical problems that separate man from achieving this wish, and that death is not only religious in character, but is also the responsibility of other professionals such as scientists and engineers.

Referências bibliográficas:

Breat, H. e Verbeke, W. (eds.) (1997). A morte na Idade Média. Revista de História, 137, (1997),145-149. Acedido em 17/02/2020 http://www.revistas.usp.br/revhistoria/article/view/64540/67185

Costa, Joana Bénard da Costa. (2012). Morre-se mal na sociedade portuguesa. Acedido em 17/02/2020 https://rr.sapo.pt/informacao_detalhe.aspx?fid=29&did=81950

Eutanásia: 13 perguntas e respostas essenciais para compreender a discussão em Portugal. TSF-Rádio Notícias, (2020). Acedido em 17/02/2020 https://www.tsf.pt/portugal/sociedade/eutanasia-13-perguntas-e-respostas-essenciais-para-compreender-a-discussao-em-portugal-11837214.html

Eutanásia e suicídio assistido. (2020). Sol. Acedido em 17/02/2020 https://sol.sapo.pt/artigo/685242/eutanasia-e-suicidio-assistido

Melo, João. (2013). A relação do homem com a morte no decorrer da história. Acedido em 19/02/2020 https://jornalggn.com.br/literatura/a-relacao-do-homem-com-a-morte-no-decorrer-da-historia/

Silva, J.N.F.S. (2012). A morte e o morrer entre o deslugar e o lugar. Lisboa: Afrontamento

Lurdes Barata

Library and Information Unit

Editorial Team