- Music Therapy in Palliative Care

Last day of the month. The newsletter is out today. It is waiting for this article in order to be published.

I have been trying to write it since the beginning of the month. "I'll do it tomorrow, maybe it'll end it the next day," I thought. And the whole month has gone by.

The confrontation with a topic has been postponed. It is a topic that few take up with the urgency that it deserves.

Many months ago, in a fantastic mini gathering with Professor José Ferro, he said: “we make a lot of plans and spend a lot to take care of babies and invest on the best for them, but we forget the end of life, we don't want to plan it”. I have never forgotten his words.

The topic is appealing, especially after asking questions to which we believe we still have few answers.

The topic is far from being well-known. Talking about Palliative Care takes us to a silent and perhaps prolonged end and this is an image that few like to confront in their own minds. But does the end always have to be like this? Silent and painful, and for how long? And then just because death has an inherent weight, it is not talked about?

Imbalance in the balance of emotions, which requires, however, a thoughtful, scrutinized reflection, so that, once understood, it is required as an integral part of the daily life of a National Health Service that has to bring together all aspects.

In the winter of last year we received a call from the Hospital, “come quickly if you want to say goodbye to him”. Scary trip to Lisbon, there was silence and it was cold, and we did not know if it was due to winter or to the warning of the loss of our father, our grandfather. Already in intensive care and with some tubes invading him, his body was cold, his skin was between white and yellow. Without reaction to the voice, to the soft kisses on the skin, there was no sign of his presence near us.

Widespread septicaemia, we were warned on the phone. His organs were failing. Lying beside him, despite all the warnings for disinfection and careful contact, I found a bit of warmth in his hands. I joined mine with his. We stayed warm only there. At that time, I quietly whispered to him that the sky in his backyard, where he always sat on summer nights, was lit by the stars. He held my hand. We think he smiled softly as if he were floating in that sky.

My grandfather did not die that night and the next morning he sat down alone in his bed and talked as if he had just woken up from a long nap. But the infections kept sticking to his body, disconnecting him from communication. The days dragged on, and with the pandemic, he became increasingly more isolated and sick, only with access to us through video call. Too weak, he could no longer hold the phone or react to anything, but every time he heard my voice he smiled, as if it were music for his fragile memory that sometimes no longer remembered me.

My grandfather died. We were unable to care for him in the final phase of his life and we do not know how he was cared for. We believe that he was well looked after, but we could not be close. We were unable to watch over him, there was no more human contact. The goodbye happened only on the day we said goodbye to the body, precisely a year ago, on Easter Sunday.

It was for all these reasons that I delayed writing about palliative care, because someone very close to me needed it and I don't know what degree of pain we were inflicting on him, just to treat him just a little more, just to keep him alive. And what about the comfort of the terminally ill? Just because they can no longer talk, can we be sure that they are being cared for without being in agony? What is the limit of pain when crossing to the end of the line?

Could it be music, or a monologue from someone close, sensory therapy?

With the purpose of educating, raising awareness and understanding others, Rui Tato Marinho, Professor and member of the Scientific Council of Master Degree Holders in Palliative Care and Paulo Pina, Professor and Doctor in Palliative Care, both from the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon, brought together the former Minister of Culture and pianist, Gabriela Canavilhas, Isabel Galriça Neto, director of the Palliative Care Unit of Luz Hospital, Raquel Gomes and the musical group SAMP, Ana Craciun, intern of year 3 in Gastroenterology and the Expresso journalist Christiana Martins as mediator of a Webinar held in early March.

Is music a therapy?

Assuming the concept of music therapy, is music then a possible cure for pain?

And what are talking about when we talk about music therapy for a palliative patient, or simply, for a patient who will receive treatment that causes him pain?

Presenting music as an integral part of the History of Humanity, Gabriela Canavilhas described it as “therapy against the pain and alienation of life”, allowing the patient to anchor and unblock his own communication. This symbology is not, however, universal. The former Minister of Culture reinforced that music has no effect if the recipient does not identify with its genre, an idea materialized in published scientific studies.

As mediator of a challenging debate, Expresso journalist Christiana Martins provoked the audience: “talking about palliative is not sexy for the media. It is easier to talk about euthanasia, but the truth is that the focus on palliative care is more humanistic”.

After watching the video of an old dancer who recalled her golden days when she was still young and did not have Alzheimer's, we listened to the music by Raquel Gomes and SAMP “Let it fly”. This is how they express themselves and perform their actions better, making music reach people at the end of the line, or children, or in prisons. One of the actions was to sing for a baby who had been abandoned by his parents, “a lifetime to get to this moment”, Raquel tells us.

Joana Pinto, music therapist, is also part of the SAMP, “there are more and more people bedridden at home, alone. And whereas at first it was not a good idea for people who were “strangers” to go to the rooms, over time they gained this privilege”.

The purpose of music is to look for sonic identity in the other, creating bridges between the patient, family members and therapists. "We want to prepare for death until the last moment and beyond the last breath".

There is a balance between the silence and the commotion of an audience of about 100 people who are confronted by the topic. And this does not happen only in other people’s families.

Let us leave death, because music does not apply only to it.

Ana Cracium is a year 3 intern at the Gastroenterology Service and works with Rui Tato Marinho. They work on a project where, despite sedation to do invasive exams such as colonoscopy and endoscopy, they ask what music the patient wants to listen to. "The biggest benefit is that patients choose their music and are free from anxiety", she says.

A doctor with a specialization in Palliative Care, Isabel Neto was confronted with the theme 26 years ago in England. It was there that it became clear to her that “music therapy is not listening to music, it is therapy”. The focus given in this conversation is the same that she gives every day in her professional activity, “it is not death itself, it is helping someone until that person dies. But it is sad to be able to intervene only in the last days when there are so many months of life before the end”.

Comforting when positively provocative, she continues to talk about the palliative care of others: “making music, or giving massage that relieves pain, is not being charitable. It is helping to live until death arrives. The person in front of us was a child, artist, professional, was a mother or father, has a whole life story and we are helping to keep that legacy. It is in the way we look at others that we may or may not manage to have their dignity returned to them”.

Defending that music therapy is a clinical therapeutic attitude, negotiated at the service of others, Paulo Pina, specialist in Palliative Care, questions whether the problem of the acceptance of these therapies will require studies with scientific evidence.

However, our Professor looks at the future that may be built with hope, especially because the younger doctors who are now beginning to be trained are much more aware of these more humanized issues about the others. And he congratulates his Faculty because “FMUL has this ability to integrate palliative care in teaching. Educating first, this is the big role that our Faculty is taking on. It is necessary to ensure that this active care must be mandatory in the NHS”.

Rui Tato Marinho is responsible for the new Palliative Care Centre of the Faculty of Medicine. He is also Director of the Gastroenterology and Hepatology Service at the Northern Lisbon Hospital Centre. He has raised the awareness of the academic community, as well as of the civil society, to the humanization of patients, specially focusing on the importance of Palliative Care. Increasingly connected to the legal world in order to study the concept of end of life, and in collaboration with the Faculty of Law, he has spread the information and put on the agenda the topic that nobody really wants to know.

Still President of the Legal Committee of the Portuguese Society of Gastroenterology, he is clinically assuming more and more care for patients.

The boundary between well-being at the end of life and death is very well separated and that is the message he wants to get across.

How did you focus more on Palliative care?

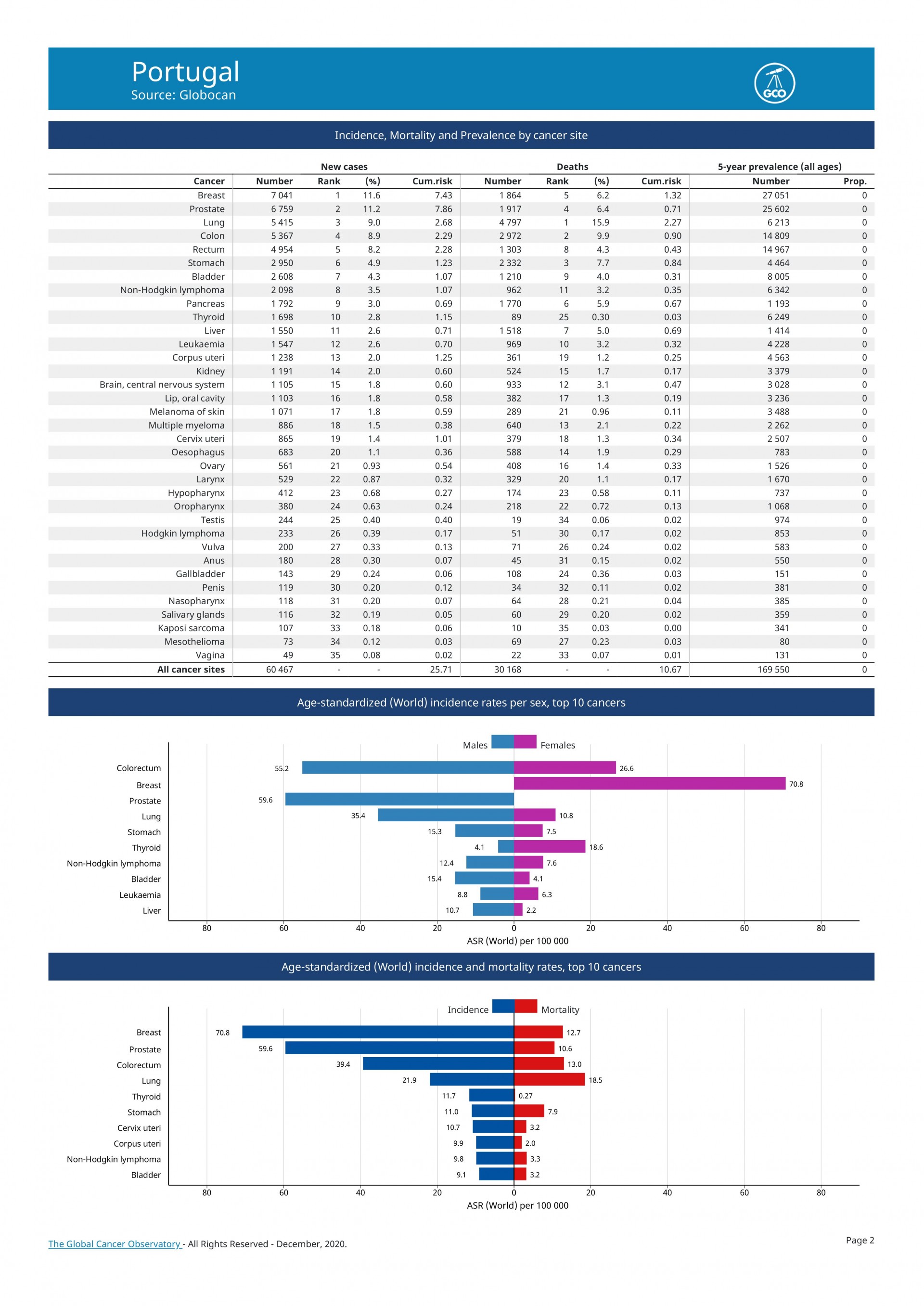

Rui Tato Marinho: About 12 years ago I realized that there was a very different world out there and that it was the world of Palliative Care. This is a topic that has only just started to be taught in some medical schools, which means that the doctors of my generation have no training in this area. My mindset changed when an ENT nurse asked me to supervise her master degree's thesis on palliative care, which was called "Pain and iatrogenic condition in terminal cancer patients". This meant that suffering is inflicted on cancer patients at a final stage of life. As I read that work, my mind cleared. I give you clear examples that caught my attention, "not having to put serum, not intubating, not having to do the procedures until the end". This is because the patients suffer with some interventions from doctors and health professionals and the question is whether it is justified. This approach changed me and transformed my way of looking at the world. Sometime later, I received an invitation from Professor António Barbosa to work with him. I started by teaching a class on liver disease and palliative care and gradually I realized that 20% of my inpatients were palliative. The truth is that Gastroenterology deals a lot with patients with oncological disease. One third of the cancers of the Portuguese are of the Digestive System. I call them the Big Five (Oesophagus, Stomach, Liver, Pancreas, Colon and Rectum).

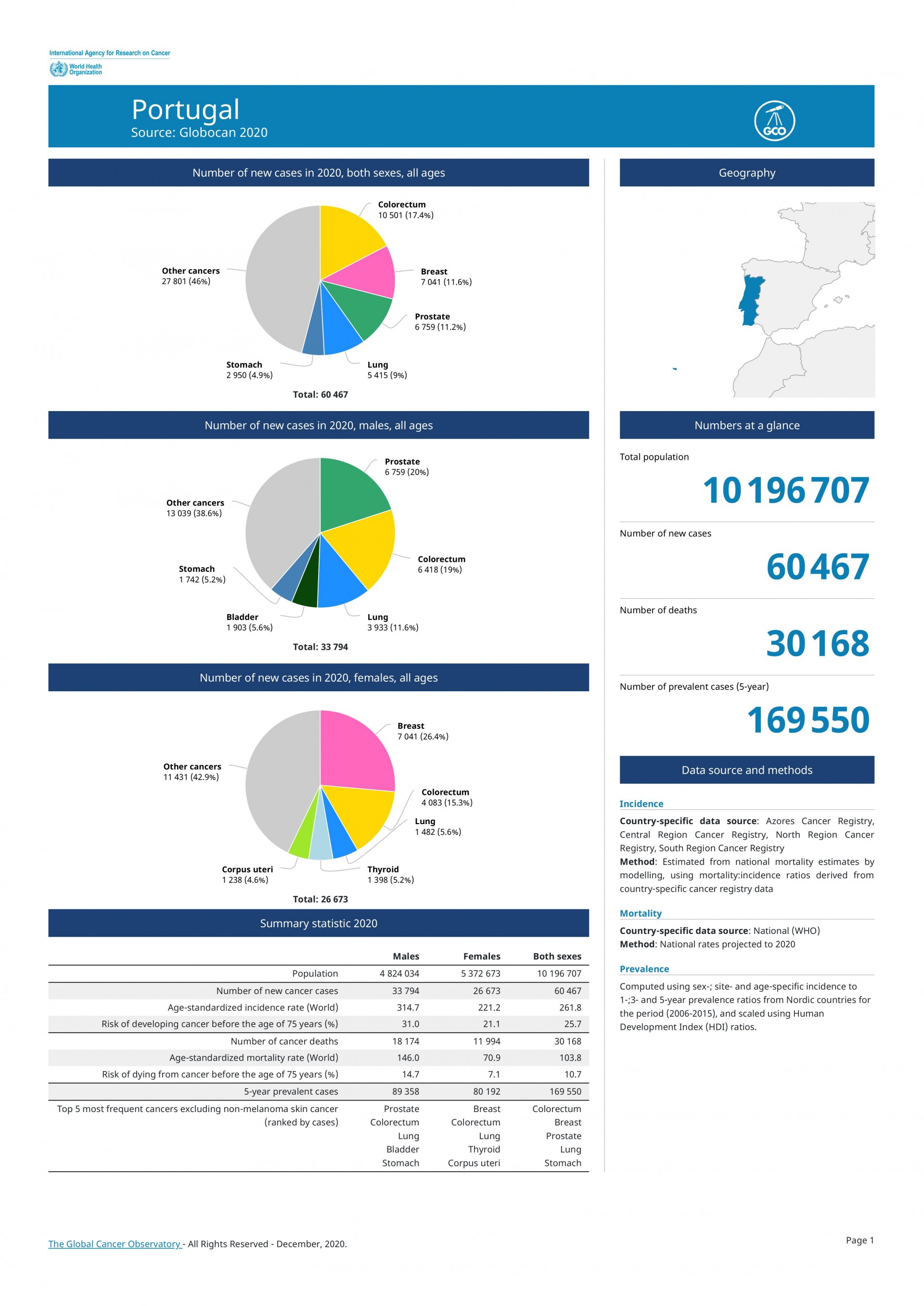

We have two cancers in the top 10 of the most deadly diseases in Portugal, that of the colon and stomach. The cancer with the highest incidence is that of the colon and rectum with more than 10,000 people per year (10,501, 17% of new cancers in Portugal), compared to breast cancer with over 7,000 women (7041), as well such as that of the prostate (6759) - Globocan, WHO 2020.

In the next 10 years, we will have more than 100,000 new cases of colon and rectal cancer.

Pancreas cancer has a worse prognosis, 4 to 5 months. It is predicted that in 2 or 3 years the latter will exceed deaths from breast cancer. The reasons are not entirely clear, but in the equation includes people's longevity, as well as obesity and the consumption of alcohol and cigarettes.

But let's go back to palliative care. Faced with this oncological situation, which I follow daily, I realized that my specialty has always included palliative care. Then I started to participate in and carry out some actions on the subject, getting involved in the legal area, in order to know what goals were enshrined in these matters. With the departure of Professor António Barbosa, I ended up taking over the area of Palliative Care.

Does our Hospital have a Palliative unit?

Rui Tato Marinho: There is a Palliative Medicine Unit, but in my opinion it needs more doctors, beds for hospitalization and a Home Support team. The Hospital has been organized in a fantastic and exemplary way to offer Intensive Care. It has organizational know-how.

No hospitalizations?

Rui Tato Marinho: No. And as a University Hospital, it should have. And there should be a home team, since there is home hospitalization. So, translation is missing. The natural tendency is for palliative medicine to become a medical specialty. It is already a skill within the Medical Association, but it will tend to become a specialty in the future. We then run the risk of not having medical correctness for not having internment or home support. The Faculty has done well in creating a Centre, it has had a Master degree for 20 years, and these are ways of bringing the two worlds together, the Hospital and the Faculty. As Director of a Service, my aim is to contribute to improving the Hospital's palliative offer. Other Services are also taking steps in this direction (Cardiology, Professor Fausto Pinto, Luís Parente Martins, Nephrology, Dr José Guerra, Dr Cristina Outerela). Mortality from liver disease is gigantic and when I arrived at this hospital 20 years ago, I thought that my work ended up being "poetry", because in every 10 patients, only one would receive a transplant, the others would end up not surviving in the medium term (2 years)

And how are these patients treated in the universe of poetry, knowing that many end up dying at home?

Rui Tato Marinho: Some are at home, but civil society also provides support. But I admit that I called myself a "death manager" as a hepatologist, because I knew and I know what will happen, I know how to calculate how much time they have left. This is the real picture.

Do patients in palliative care always die?

Rui Tato Marinho: Not always. But almost always.

(I cannot disguise my apathy at the news the Professor gives me)

There is a culture that has to change and that depends on the effectiveness of the teams. What cannot happen is the waiting time before finding the right solution for the patients, or similar situations that minimize suffering. The attitude needs to be different. Every attitude must be different in the face of death. Death is part of the natural process, there are countries that have funerals with music. They celebrate the day and bring people together, like in Mexico or Guatemala. In classes I always make a point of talking about death in clinical life and the experience that the doctor has with death. Everything is a reality process.

You organized a meeting precisely to give another meaning to the culture of death, through a Webinar entitled “Music in Palliative Care”. At that meeting, music was talked about not as a cure, but as therapy. I know you also use music for exams that are more invasive. Is music always agreed upon, or do you do it to make your team feel better?

Rui Tato Marinho: It had the participation of the pianist and former Minister of Culture, Dr Gabriela Canavilhas. I have always used jazz piano music in my consultations. We have a clinical scientific research project to understand the effects of music on the people we treat. We have to treat the patient as a whole, to see him as the whole and that doesn't just happen through music. We have to work on several areas and improve this whole. Private doctors do it very well, they pay a lot of attention to the patient, addressing the patient by his name. It is important to be empathetic and create a pleasant environment, like having day light, silence or music. It is very important because it relaxes patients. Music helps them release dopamine and feel better. Music triggers positive emotions.

Does music in palliative care also cause these emotions that we talk about?

Rui Tato Marinho: It has two aspects. On the one hand it brings positive and relaxing moments, especially if it is a song that that person would have liked a lot, it brings back memories of the good times of the past. It is the contact with the senses that we intend to stimulate. Humanizing the relationship between professional and patient, at such a difficult stage in life, is our main goal, and this also extends to the family. We need to know the name of the patient, the patient does not only need to treat that organ that is sick, it is everything, it is not that organ isolated from the rest. Today I read in a Harvard magazine that "social category is as important as skin colour and gender", that is, the entire cultural context and what has always surrounded us, can help us get closer to the patient and to understand him. To give you an example, if we have a man who has played the piano all his life, it is important that this story is known when we are treating him. He no longer tells us that, but as a doctor it is important that I know this, because I can get closer to him.

Is it in your hands to do something so that we have palliative admissions to the Hospital?

Rui Tato Marinho: It is. We all have influence, you know how? By talking. And the Faculty has given us the stage for this. The syllabus includes some (still few) Palliative Care hours and the tendency is for the workload to increase in terms of teaching.

As you can see, there are always ways of raising people’s awareness. The webinars with two former ministers help to spread information; talking to the Board of Directors can also play an important role; trying to bring in young doctors who want to come here to work and deal with these areas, is all a matter of time. You know that this pandemic has drawn a lot of attention to Intensive Care, and perhaps now we can see the importance of talking about other Care, Palliative Care. There are almost 100,000 Portuguese people a year in need of palliative support. Many of them are our Parents, Grandfathers, Portuguese who made this Country what it is. It is a humanitarian duty to take care, in an intensive or palliative way.

Perhaps the pandemic has made us refocus on the importance of sharing losses and hard times in the family. Caring with the same care as we do with those who are born, caring for those who are leaving makes me reflect, especially when it affects me personally. It makes me think who we really are and to whom we belong. "We must take better care of our parents and grandparents because it was these Portuguese who made our country, which is one of the best in the world".

You can count on me to help spread the word about, Professor!

Watch the À Conversa com... sobre os Cuidados Paliativos session:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gZV4YLP6Jw

Meet SAMP Project:

https://www.samp.pt/samp-contigo/musicoterapia/

Joana Sousa

Editorial Team